Summary: Findings provide new insights into the evolution of smooth and folded mammalian brains.

Source: Max Planck Institute.

Adhesion of migrating neurons influences the folding of the cerebral cortex.

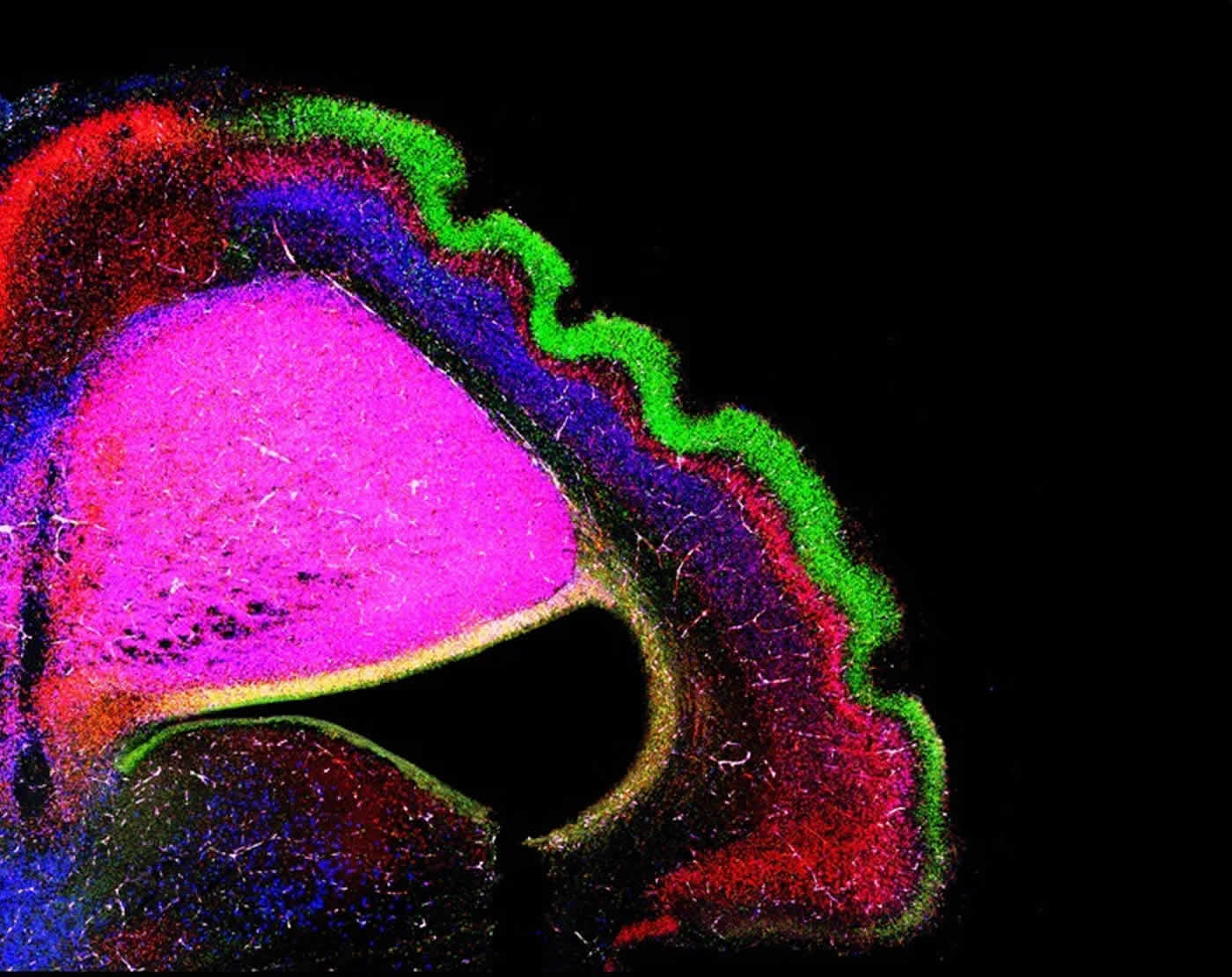

Folds in the human brain enlarge the surface of this important processing organ and in this way create more space for higher functions including thought and action. However, certain species of mammals exist whose brains have smooth surfaces, for example mice. Scientists from the Max Planck Institute of Neurobiology in Martinsried have discovered a previously unknown mechanism for brain folding. Young neurons, which migrate to the cortex during the development of a smooth-surfaced brain, have so-called FLRT receptors on their cell surface. These ensure a certain degree of adhesion between the cells and regular migratory behaviour which favours the formation of a smooth brain surface. Compared to the mouse brain, in the human brain FLRTs are much less abundant. If the expression of FLRTs in the mouse brain is reduced experimentally, folds similar to those found in the human brain form. These findings provide new insights into the evolution of smooth and folded mammalian brains.

The human brain has many grooves and furrows which enlarge the brain surface considerably compared to that of a smooth brain. Homo sapiens is not the only species to form folds in the brain, however. It is likely that the ancestral mammal, which lived around 200 million years ago, also had a folded brain. Over the course of evolution, various mammalian species lost their brain folds again. Hence mice and rats, for example, have brains with smooth surfaces.

“The evolutionary success of these and other animal species with smooth brains shows that having a brain without folds is not necessarily disadvantageous and works well for these species,” explains Rüdiger Klein, a Director at the Max Planck Institute of Neurobiology. “We were interested in how brain folds actually arise.” Up to now, scientists have shown that in folded brains, there is an expansion of progenitor cells producing a larger number of young neurons that migrate to the outer layer of the cortex during development. Hence this cellular layer becomes crowded with cells. Several mechanisms such as the rigid cranial bone prevents the cortex from simply expanding like a balloon and thus it is forced to fold to accommodate the excess cells. Studies on mice with an artificially elevated number of progenitor cells showed that this process per se is not sufficient to cause folds in the cortex, because in some cases these animals have a thicker cortex but it remains smooth. “So there must be something else that prevents the brain from folding in mice,” says Klein, explaining the starting point of the study.

In the developing mouse brain, the young neurons migrate in a homogeneous and orderly fashion to the outer area of the brain where they line up to form regular and smooth outer layers. In a previous study, Rüdiger Klein and his research team succeeded in showing that the FLRT3 molecule (pronounced flirt-3) causes the migrating neurons to adhere to each other and thus supports ordered movement. “So it made sense to assume that FLRTs might play a role in the different types of cell migration in folded and smooth brains,” says Klein. As part of their study, the researchers examined mice whose precursor cells had neither FLRT3 nor the related FLRT1 receptors. Despite the fact that there was no change in the number of precursor cells, these animals developed brains with obvious folds.

Absence of receptors promots brain folds

A combination of laboratory tests and computer simulations showed how the mouse brain developed its folds. Due to the absence of FLRT1/3 receptors, the migrating young neurons did not adhere to each other as strongly as before. “In this way, repellent mechanisms in the neighbouring cells probably gained the upper hand and forced the neurons to cluster into groups,” explains Daniel del Toro, one of the two first authors of the study. Within these cell clusters, the neurons were able to move more freely and, as a result, they were also able to migrate faster to the outer layers of the brain. Due to this altered migratory behaviour, the neurons arrived too early in the cortex and no longer distributed regularly. The scientists assume that the resulting crowding in the upper cell layer increased the pressure in this layer, and this was alleviated through the formation of folds. “The missing attraction forces between the neurons made the cortex softer and more malleable, and this probably benefited the formation of folds as well,” adds Tobias Ruff, co-first author of the study.

With this study the scientists demonstrated for the first time that adhesion of migrating neurons has a crucial impact on brain folding and that FLRT receptors play a crucial role in this process. Together with their Spanish colleagues from the Institute of Neurosciences in Alicante, Spain, the Max Planck researchers were able to demonstrate that the number of FLRT1/3 receptors in humans and ferrets, both species with folded brains, is considerably lower than in mice which have smooth brains. “Therefore it is likely that FLRTs also influence the formation of folds in our brains,” says Rüdiger Klein. These findings provide a starting point for further studies on normal and pathological folding of the mammalian brain.

Source: Stefanie Merker – Max Planck Institute

Image Source: NeuroscienceNews.com image is credited to MPI of Neurobiology, del Toro, Cederfjäll.

Original Research: Abstract for “Regulation of cerebral cortex folding by controlling neuronal migration via FLRT adhesion molecule” by Daniel del Toro, Tobias Ruff, Erik Cederfjäll, Ana Villalba, Gönül Seyit-Bremer, Víctor Borrell, and Rüdiger Klein in Cell. Published online May 4 2017 doi:10.1016/j.cell.2017.04.012

[cbtabs][cbtab title=”MLA”]Max Planck Institute “The Formation of Folds on the Surface of the Brain.” NeuroscienceNews. NeuroscienceNews, 5 May 2017.

<https://neurosciencenews.com/brain-formation-folds-6604/>.[/cbtab][cbtab title=”APA”]Max Planck Institute (2017, May 5). The Formation of Folds on the Surface of the Brain. NeuroscienceNew. Retrieved May 5, 2017 from https://neurosciencenews.com/brain-formation-folds-6604/[/cbtab][cbtab title=”Chicago”]Max Planck Institute “The Formation of Folds on the Surface of the Brain.” https://neurosciencenews.com/brain-formation-folds-6604/ (accessed May 5, 2017).[/cbtab][/cbtabs]

Abstract

Regulation of cerebral cortex folding by controlling neuronal migration via FLRT adhesion molecule

Highlights

•Flrt1/3 double-knockout mice develop macroscopic cortical sulci

•Cortex folding in mutant mice does not require progenitor cell amplification

•Absence of FLRT1/3 reduces intercellular adhesion and promotes immature neuron migration

•FLRT1/3 levels are low in the cortices of human embryos and future sulci of the ferret

Summary

The folding of the mammalian cerebral cortex into sulci and gyri is thought to be favored by the amplification of basal progenitor cells and their tangential migration. Here, we provide a molecular mechanism for the role of migration in this process by showing that changes in intercellular adhesion of migrating cortical neurons result in cortical folding. Mice with deletions of FLRT1 and FLRT3 adhesion molecules develop macroscopic sulci with preserved layered organization and radial glial morphology. Cortex folding in these mutants does not require progenitor cell amplification but is dependent on changes in neuron migration. Analyses and simulations suggest that sulcus formation in the absence of FLRT1/3 results from reduced intercellular adhesion, increased neuron migration, and clustering in the cortical plate. Notably, FLRT1/3 expression is low in the human cortex and in future sulcus areas of ferrets, suggesting that intercellular adhesion is a key regulator of cortical folding across species.

“Regulation of cerebral cortex folding by controlling neuronal migration via FLRT adhesion molecule” by Daniel del Toro, Tobias Ruff, Erik Cederfjäll, Ana Villalba, Gönül Seyit-Bremer, Víctor Borrell, and Rüdiger Klein in Cell. Published online May 4 2017 doi:10.1016/j.cell.2017.04.012