Summary: Researchers report adults with ASD have diminished neural response to hearing their own names. The study reports those diagnosed with autism display diminished activity in the right temporoparietal junction, an area of the brain associated with the processing of self-other distinction.

Source: Ghent University.

Previously, research has shown that children at risk of an autism diagnosis respond less to hearing their own name. Now, a new study from the research group EXPLORA of Ghent University shows for the first time that the brain response to hearing one’s own name is also diminished in adults with an autism diagnosis. The study was conducted by Dr. Annabel Nijhof as part of her PhD project, supervised by Prof. Dr. Roeljan Wiersema and Prof. Dr. Marcel Brass.

Whether you are at a party or in line at the supermarket, when you hear someone calling your name this usually elicits a strong orienting response. Hearing your own name typically signals that another person intends to attract your attention, and orienting to the own name is considered an important aspect of successful social interaction. Problems with social interaction and communication belong to the core symptoms of autism spectrum disorder (ASD). Studies with infants at risk for ASD have indicated that a diminished orienting response to the own name is one of the strongest predictors for developing ASD. Surprisingly however, this had not yet been studied in individuals with an ASD diagnosis.

In a new study from Ghent University, Belgium, the brain response to hearing one’s own name versus other names was compared between a group of adults with ASD, and a control group of adults without an ASD diagnosis. Participants in the study were listening to their own name, and names of close and unfamiliar others, but did not need to respond to these names. Meanwhile, their brain activity was being recorded.

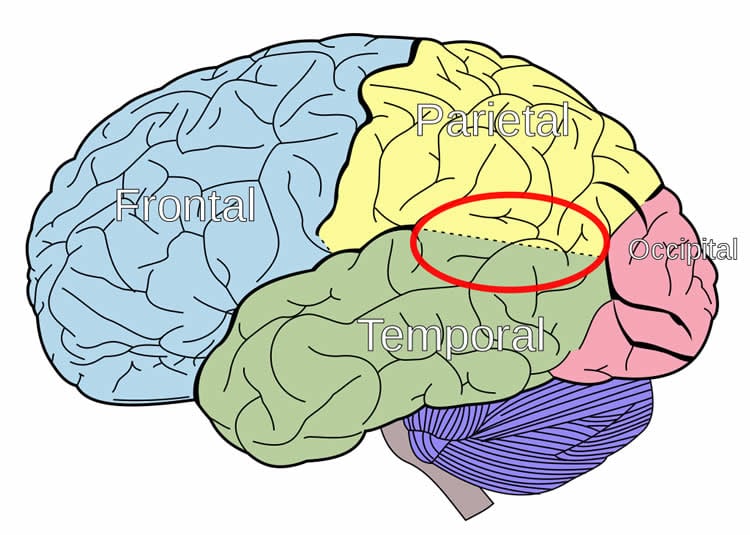

Results showed that, as expected, the brain response to one’s own name was much stronger than for other names in neurotypical adults. Strikingly, this preferential effect for the own name was completely absent in adults with ASD. Furthermore, this group difference was related to diminished activity in the right temporoparietal junction (rTPJ). Previous research has related the rTPJ to the processes of self-other distinction and mentalizing (representing another person’s mental states). During these processes, abnormal patterns of activity have been found in individuals with ASD.

This study is the first to show that brains of adults with ASD respond differently when hearing their own name, suggestive of a core deficit in self-other distinction associated with dysfunction of the rTPJ. This novel finding is important for our understanding of this complex condition and its development, and warrants further research on the possibility to use the atypical neural response to the own name as a potential biological marker of ASD.

Source: Ghent University

Publisher: Organized by NeuroscienceNews.com.

Image Source: NeuroscienceNews.com image is in the public domain.

Original Research: Abstract in Journal of Abnormal Psychology.

doi:10.1037/abn0000329

[cbtabs][cbtab title=”MLA”]Ghent University “Adults with Autism Show a Diminished Brain Response to Hearing Their Own Name.” NeuroscienceNews. NeuroscienceNews, 31 January 2018.

<https://neurosciencenews.com/autism-adults-name-8406/>.[/cbtab][cbtab title=”APA”]Ghent University (2018, January 31). Adults with Autism Show a Diminished Brain Response to Hearing Their Own Name. NeuroscienceNews. Retrieved January 31, 2018 from https://neurosciencenews.com/autism-adults-name-8406/[/cbtab][cbtab title=”Chicago”]Ghent University “Adults with Autism Show a Diminished Brain Response to Hearing Their Own Name.” https://neurosciencenews.com/autism-adults-name-8406/ (accessed January 31, 2018).[/cbtab][/cbtabs]

Abstract

Atypical neural responding to hearing one’s own name in adults with ASD

Diminished responding to hearing one’s own name is one of the earliest and strongest predictors of autism spectrum disorder (ASD). Here, we studied, for the first time, the neural correlates of hearing one’s own name in ASD. Based on existing research, we hypothesized enhancement of late parietal positive activity specifically for the own name in neurotypicals, and for this effect to be reduced in adults with ASD. Source localization analyses were conducted to estimate group differences in brain regions underlying this effect. Twenty-one adults with ASD, and 21 age- and gender-matched neurotypicals were presented with 3 categories of names (own name, close other, unknown other) as task-irrelevant deviant stimuli in an auditory oddball paradigm while electroencephalogram was recorded. As expected, late parietal positivity was observed specifically for own names in neurotypicals, indicating enhanced attention to the own name. This preferential effect was absent in the ASD group. This group difference was associated with diminished activation in the right temporoparietal junction (rTPJ) in adults with ASD. Further, a familiarity effect was found for N1 amplitude, with larger amplitudes for familiar names (own name and close other). However, groups did not differ for this effect. These findings provide evidence of atypical neural responding to hearing one’s own name in adults with ASD, suggesting a deficit in self–other distinction associated with rTPJ dysfunction.