Summary: Long duration microgravity exposure caused expansions in the combined brain and cerebrospinal fluid volumes in astronauts.

Source: RSNA

Extended periods in space have long been known to cause vision problems in astronauts. Now a new study in the journal Radiology suggests that the impact of long-duration space travel is more far-reaching, potentially causing brain volume changes and pituitary gland deformation.

More than half of the crew members on the International Space Station (ISS) have reported changes to their vision following long-duration exposure to the microgravity of space. Postflight evaluation has revealed swelling of the optic nerve, retinal hemorrhage and other ocular structural changes.

Scientists have hypothesized that chronic exposure to elevated intracranial pressure, or pressure inside the head, during spaceflight is a contributing factor to these changes. On Earth, the gravitational field creates a hydrostatic gradient, a pressure of fluid that progressively increases from your head down to your feet while standing or sitting. This pressure gradient is not present in space.

“When you’re in microgravity, fluid such as your venous blood no longer pools toward your lower extremities but redistributes headward,” said study lead author Larry A. Kramer, M.D., from the University of Texas Health Science Center at Houston. Dr. Kramer further explained, “That movement of fluid toward your head may be one of the mechanisms causing changes we are observing in the eye and intracranial compartment.”

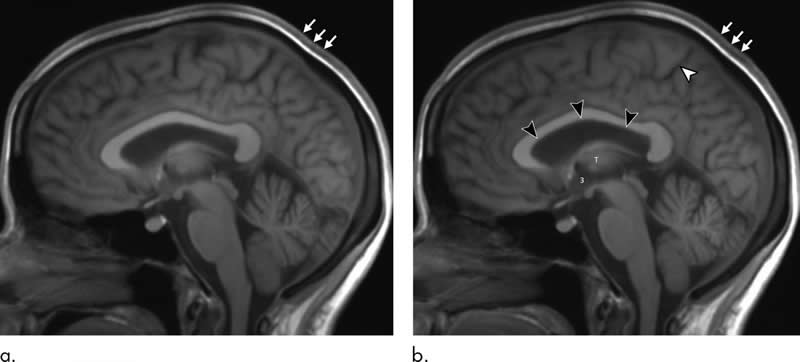

To find out more, Dr. Kramer and colleagues performed brain MRI on 11 astronauts, including 10 men and one woman, before they traveled to the ISS. The researchers followed up with MRI studies a day after the astronauts returned, and then at several intervals throughout the ensuing year.

MRI results showed that the long-duration microgravity exposure caused expansions in the astronauts’ combined brain and cerebrospinal fluid (CSF) volumes. CSF is the fluid that flows in and around the hollow spaces of the brain and spinal cord. The combined volumes remained elevated at one-year postflight, suggesting permanent alteration.

“What we identified that no one has really identified before is that there is a significant increase of volume in the brain’s white matter from preflight to postflight,” Dr. Kramer said. “White matter expansion in fact is responsible for the largest increase in combined brain and cerebrospinal fluid volumes postflight.”

MRI also showed alterations to the pituitary gland, a pea-sized structure at the base of the skull often referred to as the “master gland” because it governs the function of many other glands in the body. Most of the astronauts had MRI evidence of pituitary gland deformation suggesting elevated intracranial pressure during spaceflight.

“We found that the pituitary gland loses height and is smaller postflight than it was preflight,” Dr. Kramer said. “In addition, the dome of the pituitary gland is predominantly convex in astronauts without prior exposure to microgravity but showed evidence of flattening or concavity postflight. This type of deformation is consistent with exposure to elevated intracranial pressures.”

The researchers also observed a postflight increase in volume, on average, in the astronauts’ lateral ventricles, spaces in the brain that contain CSF. However, the overall resulting volume would not be considered outside the range of healthy adults. The changes were similar to those that occur in people who have spent long periods of bed rest with their heads tilted slightly downward in research studies simulating headward fluid shift in microgravity.

Additionally, there was increased velocity of CSF flow through the cerebral aqueduct, a narrow channel that connects the ventricles in the brain. A similar phenomenon has been seen in normal pressure hydrocephalus, a condition in which the ventricles in the brain are abnormally enlarged. Symptoms of this condition include difficulty walking, bladder control problems and dementia. To date, these symptoms have not been reported in astronauts after space travel.

The researchers are studying ways to counter the effects of microgravity. One option under consideration is the creation of artificial gravity using a large centrifuge that can spin people in either a sitting or prone position. Also under investigation is the use of negative pressure on the lower extremities as a way to counteract the headward fluid shift due to microgravity.

Dr. Kramer said the research could also have applications for non-astronauts.

“If we can better understand the mechanisms that cause ventricles to enlarge in astronauts and develop suitable countermeasures, then maybe some of these discoveries could benefit patients with normal pressure hydrocephalus and other related conditions,” he said.

About this neuroscience research article

Source:

RSNA

Media Contacts:

Linda Brooks – RSNA

Image Source:

The image is credited to RSNA.

Original Research: Closed access

“Intracranial Effects of Microgravity: A Prospective Longitudinal MRI Study”. by Larry A. Kramer, Khader M. Hasan, Michael B. Stenger, Ashot Sargsyan, Steven S. Laurie, Christian Otto, Robert J. Ploutz-Snyder, Karina Marshall-Goebel, Roy F. Riascos, Brandon R. Macias.

Radiology doi:10.1148/radiol.2020191413.

Abstract

Intracranial Effects of Microgravity: A Prospective Longitudinal MRI Study

Background

Astronauts on long-duration spaceflight missions may develop changes in ocular structure and function, which can persist for years after the return to normal gravity. Chronic exposure to elevated intracranial pressure during spaceflight is hypothesized to be a contributing factor, however, the etiologic causes remain unknown.

Purpose

To investigate the intracranial effects of microgravity by measuring combined changes in intracranial volumetric parameters, pituitary morphologic structure, and aqueductal cerebrospinal fluid (CSF) hydrodynamics relative to spaceflight and to establish a comprehensive model of recovery after return to Earth.

Materials and Methods

This prospective longitudinal MRI study enrolled astronauts with planned long-duration spaceflight. Measures were conducted before spaceflight followed by 1, 30, 90, 180, and 360 days after landing. Intracranial volumetry and aqueductal CSF hydrodynamics (CSF peak-to-peak velocity amplitude and aqueductal stroke volume) were quantified for each phase. Qualitative and quantitative changes in pre- to postflight (day 1) pituitary morphologic structure were determined. Statistical analysis included separate mixed-effects models per dependent variable with repeated observations over time.

Results

Eleven astronauts (mean age, 45 years ± 5 [standard deviation]; 10 men) showed increased mean volumes in the brain (28 mL; P < .001), white matter (26 mL; P < .001), mean lateral ventricles (2.2 mL; P < .001), and mean summated brain and CSF (33 mL; P < .001) at postflight day 1 with corresponding increases in mean aqueductal stroke volume (14.6 μL; P = .045) and mean CSF peak-to-peak velocity magnitude (2.2 cm/sec; P = .01). Summated mean brain and CSF volumes remained increased at 360 days after spaceflight (28 mL; P < .001). Qualitatively, six of 11 (55%) astronauts developed or showed exacerbated pituitary dome depression compared with baseline. Average midline pituitary height decreased from 5.9 to 5.3 mm (P < .001).

Conclusion

Long-duration spaceflight was associated with increased pituitary deformation, augmented aqueductal cerebrospinal fluid (CSF) hydrodynamics, and expansion of summated brain and CSF volumes. Summated brain and CSF volumetric expansion persisted up to 1 year into recovery, suggesting permanent alteration.

Feel Free To Share This Neuroscience News.