Summary: Children on the autism spectrum have, on average, 25% shallower brain waves than typically developing children, indicating a reason why they may have trouble entering deep sleep states.

Source: Ben-Gurion University of the Negev

Children with autism have more significant sleep difficulties caused by shallower brain waves than typically developing children, according to researchers at Ben-Gurion University of the Negev (BGU). The study was reported in Sleep, the premier journal in the field..

“For the first time, we found that children with more serious sleep issues showed brain activity that indicated more shallow and superficial sleep,” says BGU Prof. Ilan Dinstein,” head of the National Autism Research Center of Israel and a member of BGU’s Department of Psychology.

“We also found a clear relationship between the severity of sleep disturbances as reported by the parents and the reduction in sleep depth. It appears that children with autism, and especially those whose parents reported serious sleep issues, do not tire themselves out enough during the day, do not develop enough pressure to sleep and do not sleep as deeply.”

Previous studies have shown that 40% to 80% of children on the autism spectrum have some form of sleep disturbances – trouble falling asleep, frequently awakening during the night and rising early – which create severe challenges for the children and their families. Determining the causes that create these sleep disturbances is a first critical step in finding out how to mitigate them.

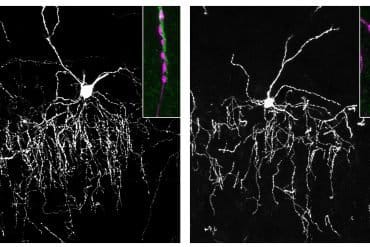

The research team, led by Prof. Dinstein, examined the brain activity of 29 children with autism and 23 children without. Their brain activity was recorded as they slept during an entire night in the Sleep Lab at Soroka University Medical Center, managed by Prof. Ariel Tarasiuk.

Normal sleep starts with periods of deep sleep that are characterized by high amplitude slow brain waves. However, the recordings revealed that the brain waves of children with autism are, on average, 25% weaker (shallower) than those of typically developing children, indicating that they have trouble entering deep sleep — the most critical aspect of achieving a restful and rejuvenating sleep experience.

Now that the team has identified the potential physiology underlying these sleep difficulties, BGU researchers are planning follow-up studies to determine how to generate deeper sleep and larger brain waves. This could include increasing daytime physical activity, behavioral therapies and pharmacological alternatives, such as medical cannabis.

Funding: The research was supported by the Simmons Foundation Autism Research Initiative.

Source:

Ben-Gurion University of the Negev

Media Contacts:

Andrew Lavin – Ben-Gurion University of the Negev

Image Source:

The image is in the public domain.

Original Research: Closed access

“Reduced sleep pressure in young children with autism”. Ilan Dinstein.

Sleep doi:10.1093/sleep/zsz309.

Abstract

Reduced sleep pressure in young children with autism

Study Objectives

Sleep disturbances and insomnia are highly prevalent in children with Autism Spectrum Disorder (ASD). Sleep homeostasis, a fundamental mechanism of sleep regulation that generates pressure to sleep as a function of wakefulness, has not been studied in children with ASD so far, and its potential contribution to their sleep disturbances remains unknown. Here, we examined whether slow wave activity (SWA), a measure that is indicative of sleep pressure, differs in children with ASD.

Methods

In this case-control study, we compared overnight electroencephalogram (EEG) recordings that were performed during Polysomnography (PSG) evaluations of 29 children with ASD and 23 typically developing children.

Results

Children with ASD exhibited significantly weaker SWA power, shallower SWA slopes, and a decreased proportion of slow wave sleep in comparison to controls. This difference was largest during the first two hours following sleep onset and decreased gradually thereafter. Furthermore, SWA power of children with ASD was significantly, negatively correlated with the time of their sleep onset in the lab and at home, as reported by parents.

Conclusions

These results suggest that children with ASD may have a dysregulation of sleep homeostasis that is manifested in reduced sleep pressure. The extent of this dysregulation in individual children was apparent in the amplitude of their SWA power, which was indicative of the severity of their individual sleep disturbances. We, therefore, suggest that disrupted homeostatic sleep regulation may contribute to sleep disturbances in children with ASD.