Some people are born without the ability to visualize images.

If counting sheep is an abstract concept, or you are unable to visualise the faces of loved ones, you could have aphantasia – a newly defined condition to describe people who are born without a “mind’s eye”.

Some people report a significant impact on their lives from being unable to visualise memories of their partners, or departed relatives. Others say that descriptive writing is meaningless to them, and careers such as architecture or design are closed to them, as they would not be able to visualise an end product.

Cognitive neurologist Professor Adam Zeman, at the University of Exeter Medical School, has revisited the concept of people who cannot visualise, which was first identified by Sir Francis Galton in 1880 A 20th century survey suggested that this may be true of 2.5% of the population – yet until now, this phenomenon has remained largely unexplored.

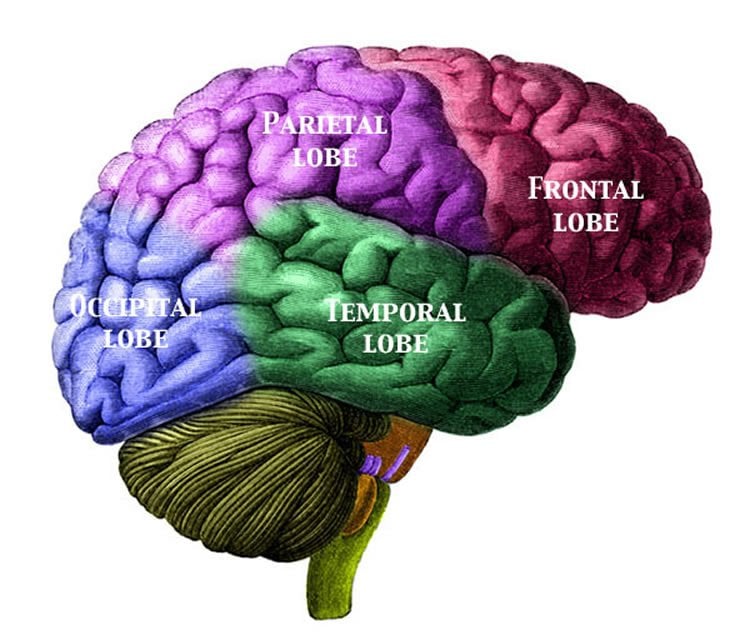

Visualisation is the result of activity in a network of of regions widely distributed across the brain, working together to enable us to generate images on the basis of our memory of how things look. These regions include areas in the frontal and parietal lobes, which ‘organise’ the process of visualisation, together with areas in the temporal and occipital lobes, which represent the items we wish to call to the mind’s eye, and give visualisation its ‘visual’ feel. An inability to visualise could result from an alteration of function at several points in this network. This problem has been described previously following major brain damage and in the context of mood disorder. Now, Professor Zeman and his team are conducting further studies to find out more about why some people are born with poor or diminished visual imagery ability.

The recent research came about by serendipity. The American science journalist, Carl Zimmer, wrote an article in Discover magazine about a previous paper by Professor Zeman reporting a man who lost his mind’s eye in his sixties following a cardiac procedure. Professor Zeman was then contacted by 21 individuals who recognised their own experience in the Discover article, but had never been able to imagine. Professor Zeman and colleagues describe these patients’ experience in a paper just published in the journal Cortex.

One of the responders, Tom Ebeyer, 25, from Ontario, Canada, keenly felt a sense of loss when he realised at the age of 21 that his girlfriend could visually “see” things in her mind’s eye in a way that he could not.

Tom said: “It had a serious emotional impact. I began to feel isolated – unable to do something so central to the average human experience. The ability to recall memories and experiences, the smell of flowers or the sound of a loved one’s voice; before I discovered that recalling these things was humanly possible, I wasn’t even aware of what I was missing out on. The realisation did help me to understand why I am a slow at reading text, and why I perform poorly on memorisation tests, despite my best efforts.”

For Tom, all types of sense are affected. He cannot conjure up any sound, texture, taste, smell, emotion, or any other type of imagery.

He said the condition had severely affected his relationships, as he is unable to visualise his partner if they are not together, or to recall shared experiences. He said: “After the passing of my mother, I was extremely distraught in that I could not reminisce on the memories we had together. I can remember factually the things we did together, but never an image. After seven years, I hardly remember her.”

“To have the condition researched and defined brings me great pleasure. Not only do I now have an official title to refer to the condition while discussing it with my peers, but the knowledge that professionals are recognising its reality gives me hope that further understanding is still to come.”

Niel Kenmuir, 39, from Lancaster in the UK, first realised he could not visualise images at primary school. “I can remember not understanding what ‘counting sheep’ entailed when I couldn’t sleep. I assumed they meant it in a figurative sense. When I tried it myself, I found myself turning my head to watch invisible sheep fly by. I’ve spent years looking online for information about my condition, and finding nothing. I’m very happy that it is now being researched and defined.”

Niel works in a bookshop and is an avid reader, but avoids books with vivid landscape descriptions as they bring nothing to mind for him. “I just find myself going through the motion of reading the words without any image coming to mind,” he said. “I usually have to go back and read a passage about a visual description several times – it’s almost meaningless.”

Niel studied philosophy, which is rich in visual imagery, but this aspect was lost on him. The way he explains it, though, he does understand the mechanics behind it. He said: “The mind’s eye is a canvas, and the neurones work together to project onto it. The neurones are all working fine, but I don’t have the canvas”.

Asked if it had impacted on his life, he said: “I have never been ambitious, and wondered if an inability to ‘imagine myself in a place ten years from now’ as a concrete image has affected this. I also find it difficult to jump from abstract thought to concrete examples, although I think a positive consequence is that I am perhaps better at thinking abstractly than many other people.”

Professor Zeman said: “This intriguing variation in human experience has received little attention. Our participants mostly have some first-hand knowledge of imagery through their dreams: our study revealed an interesting dissociation between voluntary imagery, which is absent or much reduced in these individuals, and involuntary imagery, for example in dreams, which is usually preserved.”

Professor Zeman is pursuing the study of aphantasia through an interdisciplinary project funded by the Arts and Humanities Research Council (AHRC), The Eye’s Mind – a study of the neural basis of visual imagination and its role in culture. The AHRC project involves, among others, the artist Susan Aldworth, art historian John Onians and philosopher, Fiona Macpherson.

Source: Louise Vennells – University of Exeter

Image Source: The image is credited to Camazine and is licensed CC BY 3.0

Original Research: Abstract for “Lives without imagery – Congenital aphantasia” by Adam Zeman, Michaela Dewar, and Sergio Della Sala in Cortex. Published online June 3 2015 doi:10.1016/j.cortex.2015.05.019