Summary: A new study shows that integrating artificial intelligence with advanced proximity and pressure sensors allows a commercial bionic hand to grasp objects in a natural, intuitive way—reducing cognitive effort for amputees. By training an artificial neural network on grasping postures, each finger could independently “see” objects and automatically move into the correct position, improving grip security and precision.

Participants performed everyday tasks such as lifting cups and picking up small items with far less mental strain and without extensive training. The shared-control system balanced human intent with machine assistance, enabling effortless, lifelike use of a prosthetic hand.

Key Facts

- Natural Control: AI-enabled fingers used proximity and pressure sensors to form stable, intuitive grasps.

- Reduced Cognitive Load: Participants performed tasks with less mental effort and greater precision.

- Shared Autonomy: The system blended user control with AI assistance to avoid conflict and enhance dexterity.

Source: University of Utah

Whether you’re reaching for a mug, a pencil or someone’s hand, you don’t need to consciously instruct each of your fingers on where they need to go to get a proper grip.

The loss of that intrinsic ability is one of the many challenges people with prosthetic arms and hands face. Even with the most advanced robotic prostheses, these everyday activities come with an added cognitive burden as users purposefully open and close their fingers around a target.

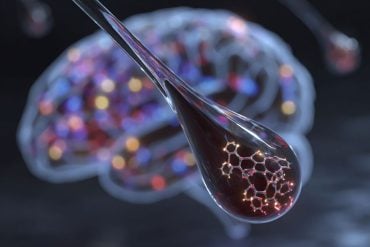

Researchers at the University of Utah are now using artificial intelligence to solve this problem. By integrating proximity and pressure sensors into a commercial bionic hand, and then training an artificial neural network on grasping postures, the researchers developed an autonomous approach that is more like the natural, intuitive way we grip objects. When working in tandem with the artificial intelligence, study participants demonstrated greater grip security, greater grip precision and less mental effort.

Critically, the participants were able to perform numerous everyday tasks, such as picking up small objects and raising a cup, using different gripping styles, all without extensive training or practice.

The study was led by engineering professor Jacob A. George and Marshall Trout, a postdoctoral researcher in the Utah NeuroRobotics Lab, and appears Tuesday in the journal Nature Communications.

“As lifelike as bionic arms are becoming, controlling them is still not easy or intuitive,” Trout said. “Nearly half of all users will abandon their prosthesis, often citing their poor controls and cognitive burden.”

One problem is that most commercial bionic arms and hands have no way of replicating the sense of touch that normally gives us intuitive, reflexive ways of grasping objects. Dexterity is not simply a matter of sensory feedback, however. We also have subconscious models in our brains that simulate and anticipate hand-object interactions; a “smart” hand would also need to learn these automatic responses over time.

The Utah researchers addressed the first problem by outfitting an artificial hand, manufactured by TASKA Prosthetics, with custom fingertips. In addition to detecting pressure, these fingertips were equipped with optical proximity sensors designed to replicate the finest sense of touch. The fingers could detect an effectively weightless cotton ball being dropped on them, for example.

For the second problem, they trained an artificial neural network model on the proximity data so that the fingers would naturally move to the exact distance necessary to form a perfect grasp of the object. Because each finger has its own sensor and can “see” in front of it, each digit works in parallel to form a perfect, stable grasp across any object.

But one problem still remained. What if the user didn’t intend to grasp the object in that exact manner? What if, for example, they wanted to open their hand to drop the object? To address this final piece of the puzzle, the researchers created a bioinspired approach that involves sharing control between the user and the AI agent. The success of the approach relied on finding the right balance between human and machine control.

“What we don’t want is the user fighting the machine for control. In contrast, here the machine improved the precision of the user while also making the tasks easier,” Trout said. “In essence, the machine augmented their natural control so that they could complete tasks without having to think about them.”

The researchers also conducted studies with four participants whose amputations fall between the elbow and wrist. In addition to improved performance on standardized tasks, they also attempted multiple everyday activities that required fine motor control. Simple tasks, like drinking from a plastic cup, can be incredibly difficult for an amputee; squeeze too soft and you’ll drop it, but squeeze too hard and you’ll break it.

“By adding some artificial intelligence, we were able to offload this aspect of grasping to the prosthesis itself,” George said. “The end result is more intuitive and more dexterous control, which allows simple tasks to be simple again.”

George is the Solzbacher-Chen Endowed Professor in the John and Marcia Price College of Engineering’s Department of Electrical & Computer Engineering and the Spencer Fox Eccles School of Medicine’s Department of Physical Medicine and Rehabilitation.

This work is part of the Utah NeuroRobotics Lab’s larger vision to improve the quality of life for amputees.

“The study team is also exploring implanted neural interfaces that allow individuals to control prostheses with their mind and even get a sense of touch coming back from this,” George said. “Next steps, the team plans to blend these technologies, so that their enhanced sensors can improve tactile function and the intelligent prosthesis can blend seamlessly with thought-based control.”

The study was published online Dec.9 in Nature Communications under the title “Shared human-machine control of an intelligent bionic hand improves grasping and decreases cognitive burden for transradial amputees.”

Coauthors include NeuroRobotics Lab members Fredi Mino, Connor Olsen and Taylor Hansen, as well as Masaru Teramoto, research assistant professor in the School of Medicine’s Division of Physical Medicine & Rehabilitation, David Warren, research associate professor emeritus in the Department of Biomedical Engineering, and Jacob Segil of the University of Colorado Boulder.

Funding: Funding came from the National Institutes of Health and National Science Foundation.

Key Questions Answered:

A: The system uses fingertip proximity and pressure sensors plus a trained neural network to automatically position each finger for a stable, natural grasp.

A: No. A shared-control framework blends human intent with machine assistance, preventing conflict and preserving user agency.

A: Current prostheses require high cognitive effort; the new AI-driven system restores intuitive, low-effort grasping similar to natural hand function.

Editorial Notes:

- This article was edited by a Neuroscience News editor.

- Journal paper reviewed in full.

- Additional context added by our staff.

About this neurotech and robotics research news

Author: Evan Lerner

Source: University of Utah

Contact: Evan Lerner – University of Utah

Image: The image is credited to Neuroscience News

Original Research: Open access.

“Shared human-machine control of an intelligent bionic hand improves grasping and decreases cognitive burden for transradial amputees” by Jacob A. George et al. Nature Communications

Abstract

Shared human-machine control of an intelligent bionic hand improves grasping and decreases cognitive burden for transradial amputees

Bionic hands can replicate many movements of the human hand, but our ability to intuitively control these bionic hands is limited. Humans’ manual dexterity is partly due to control loops driven by sensory feedback.

Here, we describe the integration of proximity and pressure sensors into a commercial prosthesis to enable autonomous grasping and show that continuously sharing control between the autonomous hand and the user improves dexterity and user experience.

Artificial intelligence moved each finger to the point of contact while the user controlled the grasp with surface electromyography. A bioinspired dynamically weighted sum merged machine and user intent. Shared control resulted in greater grip security, greater grip precision, and less cognitive burden.

Demonstrations include intact and amputee participants using the modified prosthesis to perform real-world tasks with different grip patterns. Thus, granting some autonomy to bionic hands presents a translatable and generalizable approach towards more dexterous and intuitive control.