Summary: Researchers confirm humans have heightened visual awareness when it comes to snakes.

Source: Nagoya University.

Nagoya University research team uses new image processing tool to confirm human visual system has evolved specifically to detect snakes

Some studies have suggested that the visual systems of humans and other primates are finely tuned to identify dangerous creatures such as snakes and spiders. This is understandable because, among our ancestors, those who were more able to see and avoid these animals would have been more likely to pass on their genes to the next generation. However, it has been difficult to compare the recognition of different animals in an unbiased way because of their different shapes, anatomical features, and levels of camouflage.

In a study reported recently in PLOS ONE, a pair of researchers at Nagoya University obtained strong support for the idea that humans have heightened visual awareness of snakes. The researchers applied an image manipulation tool and revealed that subjects could identify snakes in much more blurry images than they could identify other harmless animals in equivalent images.

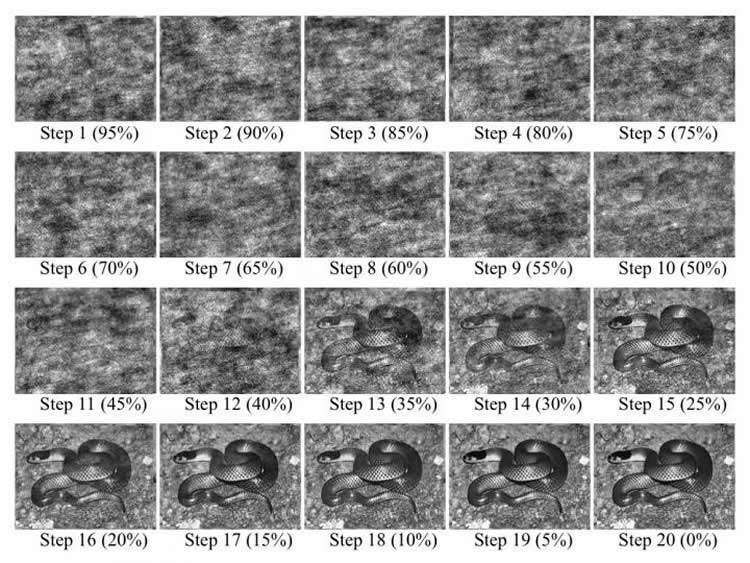

The tool, called Random Image Structure Evolution (RISE), was used to create a series of 20 images of snakes, birds, cats, and fish, ranging from completely blurred to completely clear. The pair then asked subjects to views these images in order of increasing clarity until they could identify the animal in the picture.

“Because of the algorithm that it uses, RISE produces images that allow unbiased comparison between the recognition of different animals,” first author Nobuyuki Kawai says. “In the images, the animals are ‘camouflaged’ in a uniform way, representing typical conditions in which animals are encountered in the wild.”

The snakes were increasingly well-identified in the sixth to eighth of 20 images, while the subjects often needed to see the less blurred ninth or tenth images to identity the other animals. “This suggests that humans are primed to pick out snakes even in dense undergrowth, in a way that isn’t activated for other animals that aren’t a threat,” co-author Hongshen He explains.

The findings confirm the Snake Detection Theory; namely, that the visual system of humans and primates has specifically evolved in a way that facilitates picking out of dangerous animals. This work augments understanding of the evolutionary pressures placed on our ancestors.

Funding: The study was funded by Japanese Society for the Promotion of Science.

Source: Koomi Sung – Nagoya University

Image Source: This NeuroscienceNews.com image is credited to Nobuyuki Kawai.

Original Research: Full open access research for “Breaking Snake Camouflage: Humans Detect Snakes More Accurately than Other Animals under Less Discernible Visual Conditions” by Nobuyuki Kawai and Hongshen He in PLOS ONE. Published online October 26 2016 doi:10.1371/journal.pone.0164342

[cbtabs][cbtab title=”MLA”]Nagoya University. “Humans Recognize Partially Obscured Snakes More Easily Than Other Animals.” NeuroscienceNews. NeuroscienceNews, 8 November 2016.

<https://neurosciencenews.com/snake-recognition-vision-5460/>.[/cbtab][cbtab title=”APA”]Nagoya University. (2016, November 8). Humans Recognize Partially Obscured Snakes More Easily Than Other Animals. NeuroscienceNews. Retrieved November 8, 2016 from https://neurosciencenews.com/snake-recognition-vision-5460/[/cbtab][cbtab title=”Chicago”]Nagoya University. “Humans Recognize Partially Obscured Snakes More Easily Than Other Animals.” https://neurosciencenews.com/snake-recognition-vision-5460/ (accessed November 8, 2016).[/cbtab][/cbtabs]

Abstract

Breaking Snake Camouflage: Humans Detect Snakes More Accurately than Other Animals under Less Discernible Visual Conditions

Humans and non-human primates are extremely sensitive to snakes as exemplified by their ability to detect pictures of snakes more quickly than those of other animals. These findings are consistent with the Snake Detection Theory, which hypothesizes that as predators, snakes were a major source of evolutionary selection that favored expansion of the visual system of primates for rapid snake detection. Many snakes use camouflage to conceal themselves from both prey and their own predators, making it very challenging to detect them. If snakes have acted as a selective pressure on primate visual systems, they should be more easily detected than other animals under difficult visual conditions. Here we tested whether humans discerned images of snakes more accurately than those of non-threatening animals (e.g., birds, cats, or fish) under conditions of less perceptual information by presenting a series of degraded images with the Random Image Structure Evolution technique (interpolation of random noise). We find that participants recognize mosaic images of snakes, which were regarded as functionally equivalent to camouflage, more accurately than those of other animals under dissolved conditions. The present study supports the Snake Detection Theory by showing that humans have a visual system that accurately recognizes snakes under less discernible visual conditions.

“Breaking Snake Camouflage: Humans Detect Snakes More Accurately than Other Animals under Less Discernible Visual Conditions” by Nobuyuki Kawai and Hongshen He in PLOS ONE. Published online October 26 2016 doi:10.1371/journal.pone.0164342