Summary: A new PNAS study reveals typically developing children experience neurogenesis in the amygdala as they become adults. However, for those with autism, the amygdala loses neurons as they age.

Source: UC Davis.

In a striking new finding, researchers at the UC Davis MIND Institute found that typically-developing children gain more neurons in a region of the brain that governs social and emotional behavior, the amygdala, as they become adults. This phenomenon does not happen in people with autism spectrum disorder (ASD). Instead, children with ASD have too many neurons early on and then appear to lose those neurons as they become adults. The findings were published today in the journal Proceedings of the National Academy of Sciences (PNAS).

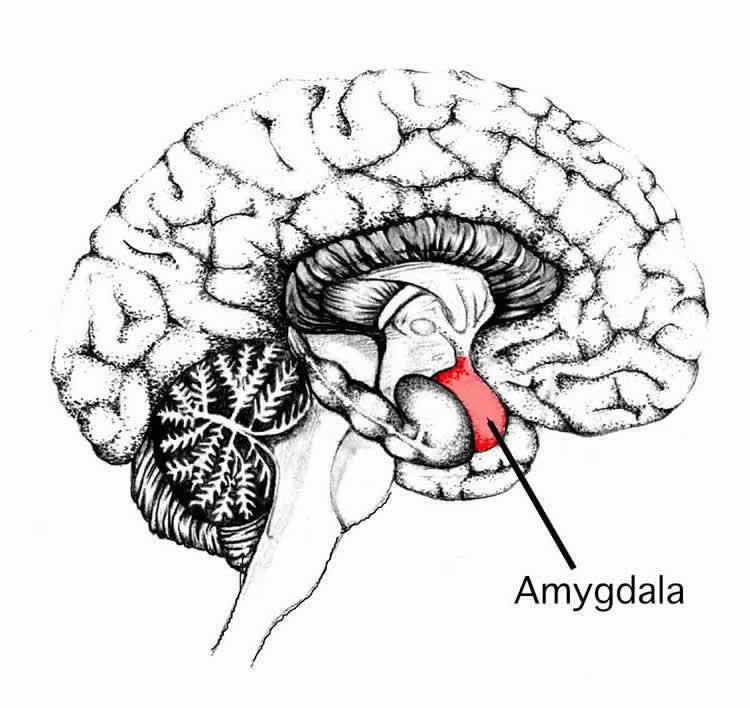

The amygdala is a small almond-shaped group of 13 regions (nuclei) that work as a danger detector in the brain to regulate anxiety and social interactions. Amygdala dysfunction has been linked to many psychiatric and neurodevelopmental disorders, including ASD, schizophrenia, bipolar disorder and depression.

“The amygdala is a unique brain structure in that it grows dramatically during adolescence, longer than other brain regions, as we become more socially and emotionally mature,” said Cynthia Schumann, associate professor in the Department of Psychiatry and Behavioral Sciences at the UC Davis MIND Institute and senior author of the paper. “Any deviation from this normal path of development can profoundly influence human behavior.” To understand what cellular factors underlie amygdala development, the team studied 52 postmortem human brains, both neurotypical and ASD, ranging from 2 to 48 years of age.

“We were surprised to find that the number of neurons in one of the amygdala regions increased by more than 30% from childhood to adulthood in typically-developing individuals,” said Schumann.

The picture was quite different in people with ASD. There were more neurons in young children with ASD, but as they got older, those numbers went down.

“We don’t know if having too many amygdala neurons early in development in ASD is related to the apparent loss later on,” said Schumann. “It’s possible that having too many neurons early on could contribute to anxiety and challenges with social interactions. However, with time, that constant activity could wear on the system and lead to neuron loss.”

Schumann and her team believe that if they can explain how the cells are changing throughout adolescence in the amygdala, it might be possible to intervene and treat symptoms such as anxiety that develop in people with autism and other neurodevelopmental and psychiatric disorders.

Other authors included Thomas A. Avino, Nicole Barger, Martha V. Vargas, Erin L. Carlson, David G. Amaral and Melissa D. Bauman.

Funding: Research reported in this publication was supported by the National Institute of Mental Health of the National Institutes of Health (R01MH097236).

Source: Shawn Kramer – UC Davis

Publisher: Organized by NeuroscienceNews.com.

Image Source: NeuroscienceNews.com image is in the public domain.

Original Research: Open access research in PNAS.

doi:10.1073/pnas.1801912115

[cbtabs][cbtab title=”MLA”]UC Davis “Amygdala Neurons Increase as Children Become Adults; Except in Autism.” NeuroscienceNews. NeuroscienceNews, 20 March 2018.

<https://neurosciencenews.com/autism-amygdala-neurogenesis-8675/>.[/cbtab][cbtab title=”APA”]UC Davis (2018, March 20). Amygdala Neurons Increase as Children Become Adults; Except in Autism. NeuroscienceNews. Retrieved March 20, 2018 from https://neurosciencenews.com/autism-amygdala-neurogenesis-8675/[/cbtab][cbtab title=”Chicago”]UC Davis “Amygdala Neurons Increase as Children Become Adults; Except in Autism.” https://neurosciencenews.com/autism-amygdala-neurogenesis-8675/ (accessed March 20, 2018).[/cbtab][/cbtabs]

Abstract

Neuron numbers increase in the human amygdala from birth to adulthood, but not in autism

Remarkably little is known about the postnatal cellular development of the human amygdala. It plays a central role in mediating emotional behavior and has an unusually protracted development well into adulthood, increasing in size by 40% from youth to adulthood. Variation from this typical neurodevelopmental trajectory could have profound implications on normal emotional development. We report the results of a stereological analysis of the number of neurons in amygdala nuclei of 52 human brains ranging from 2 to 48 years of age [24 neurotypical and 28 autism spectrum disorder (ASD)]. In neurotypical development, the number of mature neurons in the basal and accessory basal nuclei increases from childhood to adulthood, coinciding with a decrease of immature neurons within the paralaminar nucleus. Individuals with ASD, in contrast, show an initial excess of amygdala neurons during childhood, followed by a reduction in adulthood across nuclei. We propose that there is a long-term contribution of mature neurons from the paralaminar nucleus to other nuclei of the neurotypical human amygdala and that this growth trajectory may be altered in ASD, potentially underlying the volumetric changes detected in ASD and other neurodevelopmental or neuropsychiatric disorders.