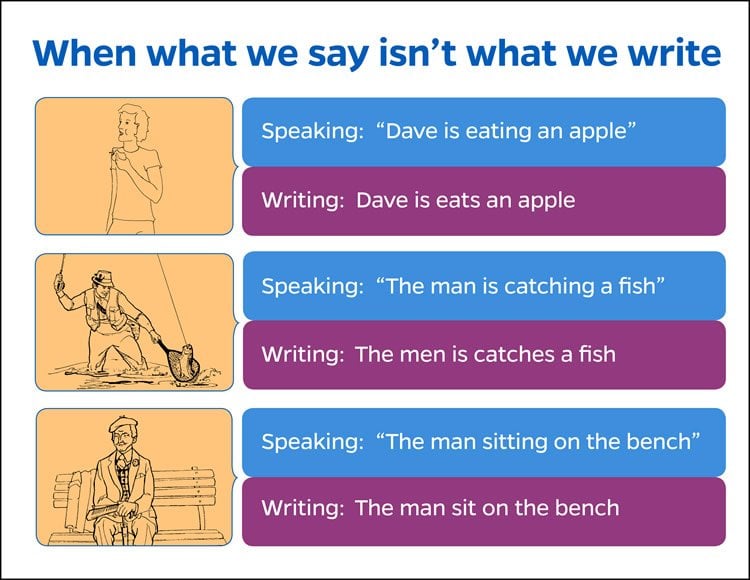

Out loud, someone says, “The man is catching a fish.” The same person then takes pen to paper and writes, “The men is catches a fish.”

Although the human ability to write evolved from our ability to speak, in the brain, writing and talking are now such independent systems that someone who can’t write a grammatically correct sentence may be able say it aloud flawlessly, discovered a team led by Johns Hopkins University cognitive scientist Brenda Rapp.

In a paper published this week in the journal Psychological Science, Rapp’s team found it’s possible to damage the speaking part of the brain but leave the writing part unaffected — and vice versa — even when dealing with morphemes, the tiniest meaningful components of the language system including suffixes like “er,” “ing” and “ed.”

“Actually seeing people say one thing and — at the same time — write another is startling and surprising. We don’t expect that we would produce different words in speech and writing,” said Rapp, a professor in the Department of Cognitive Science in the Krieger School of Arts and Sciences. “It’s as though there were two quasi independent language systems in the brain.”

The team wanted to understand how the brain organizes knowledge of written language — reading and spelling — since that there is a genetic blueprint for spoken language but not written. More specifically, they wanted to know if written language was dependent on spoken language in literate adults. If it was, then one would expect to see similar errors in speech and writing. If it wasn’t, one might see that people don’t necessarily write what they say.

The team, that included Simon Fischer-Baum of Rice University and Michele Miozzo of Columbia University, both cognitive scientists, studied five stroke victims with aphasia, or difficulty communicating. Four of them had difficulties writing sentences with the proper suffixes, but had few problems speaking the same sentences. The last individual had the opposite problem — trouble with speaking but unaffected writing.

The researchers showed the individuals pictures and asked them to describe the action. One person would say, “the boy is walking,” but write, “the boy is walked.” Or another would say, “Dave is eating an apple” and then write, “Dave is eats an apple.”

The findings reveal that writing and speaking are supported by different parts of the brain — and not just in terms of motor control in the hand and mouth, but in the high-level aspects of word construction.

“We found that the brain is not just a ‘dumb’ machine that knows about letters and their order, but that it is ‘smart’ and sophisticated and knows about word parts and how they fit together,” Rapp said. “When you damage the brain, you might damage certain morphemes but not others in writing but not speaking, or vice versa.”

This understanding of how the adult brain differentiates word parts could help educators as they teach children to read and write, Rapp said. It could lead to better therapies for those suffering aphasia.

Funding: Parts of this research was funded by National Institutes on Deafness and Other Communication Disorders Grant DC012283.

Source: Jill Rosen – Johns Hopkins University

Image Source: The image is adapted from the Johns Hopkins University press release

Original Research: Abstract for “Modality and Morphology: What We Write May Not Be What We Say” by Brenda Rapp, Simon Fischer-Baum, and Michele Miozzo in Psychological Science. Published online April 29 2015 doi:10.1177/0956797615573520

Abstract

Modality and Morphology: What We Write May Not Be What We Say

Written language is an evolutionarily recent human invention; consequently, its neural substrates cannot be determined by the genetic code. How, then, does the brain incorporate skills of this type? One possibility is that written language is dependent on evolutionarily older skills, such as spoken language; another is that dedicated substrates develop with expertise. If written language does depend on spoken language, then acquired deficits of spoken and written language should necessarily co-occur. Alternatively, if at least some substrates are dedicated to written language, such deficits may doubly dissociate. We report on 5 individuals with aphasia, documenting a double dissociation in which the production of affixes (e.g., the -ing in jumping) is disrupted in writing but not speaking or vice versa. The findings reveal that written- and spoken-language systems are considerably independent from the standpoint of morpho-orthographic operations. Understanding this independence of the orthographic system in adults has implications for the education and rehabilitation of people with written-language deficits.

“Modality and Morphology: What We Write May Not Be What We Say” by Brenda Rapp, Simon Fischer-Baum, and Michele Miozzo in Psychological Science. Published online April 29 2015 doi:10.1177/0956797615573520