Summary: Concussions can leave lasting effects on vision, with nearly half of young patients experiencing disorders that disrupt daily life and delay return to normal activities. A new study shows that 12 weeks of targeted vision therapy restored normal vision in almost 90% of adolescents and young adults, compared to only 10% who improved without therapy.

Researchers also found that traditional vision exercises used in non-concussed patients work equally well for those with concussion-related eye deficits. These results highlight the need for early intervention, insurance coverage, and potentially at-home virtual reality therapies to expand access.

Key Facts:

- High Prevalence: About 50% of young people with persistent concussion symptoms develop eye coordination disorders.

- Therapy Success: 90% of patients improved with 12 weeks of vision therapy compared to under 10% without treatment.

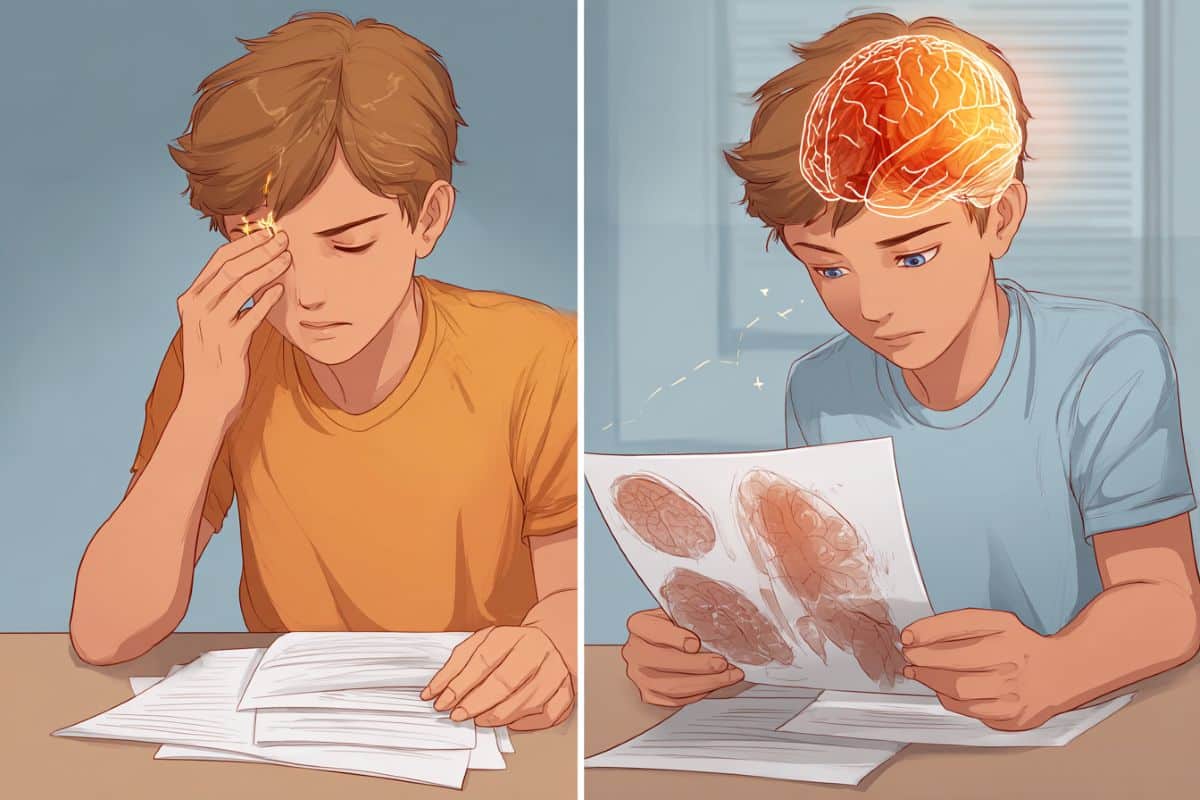

- Brain Changes: fMRI scans showed therapy altered brain activity, strengthening connections in eye-related regions.

Source: NJIT

Nearly half of adolescents and young adults with lingering symptoms of concussion suffer from eye coordination disorders that cause double and blurred vision, headaches and difficulties concentrating.

“These conditions make it hard to read books, work on a computer or even use a smartphone, and the impact on cognition and learning can be severe. They also delay the return to sports, work and driving for young people,” said Tara Alvarez, a distinguished professor of biomedical engineering at NJIT.

In a recent study published in the British Journal of Sports Medicine, Alvarez and colleagues show for the first time that there is an effective way to treat these post-concussion disorders.

They are known as convergence insufficiency (CI), a condition causing double vision in which the muscles that control eye movements don’t coordinate to focus on near objects, and accommodation insufficiency (AI), which makes objects appear blurry.

With a multi-institutional team of engineers, optometrists, vision researchers, sports medicine physicians and biostatisticians, Alvarez set out four years ago to gather data that could potentially establish guidelines to help clinicians diagnose and treat patients. It would, for example, enable data-driven decisions about the timing, dosing and need for treatment.

“We wanted to come up with best practices to optimize therapy for individual patients, as well as the means to verify the results,” she said, noting, “Physicians, for example, have a difficult time clearing people to return to activities. They base their decisions on their experience in identifying symptoms, because they lack quantitative measures to determine more precisely when it’s safe.”

Backed by a $3 million grant from the National Eye Institute of the National Institutes of Health, the team enrolled 106 patients from ages 11 to 25 with one to multiple concussions and persisting symptoms for one to six months after their most recent injury.

After 12 weeks of vision therapy, nearly 90% of patients in the study were able to see normally, compared to just under 10% in the group that monitored symptoms to determine whether they would go away naturally. A small number of patients in the treatment group required an additional four weeks to improve sufficiently.

“A practical conclusion is that someone with a concussion-related vision issue really shouldn’t delay starting therapy if symptoms disrupt daily activities,” said Mitchell Scheiman, O.D., Ph.D., senior associate dean of research at the Pennsylvania College of Optometry at Drexel University, and the study’s lead optometrist.

“People who have concussions and haven’t recovered are struggling with their lives. At first glance, six weeks might seem like a short time, but if you have a concussion, six weeks is a long time.”

Critically, the team also learned that the methods used to treat non-concussed patients, including several exercises to strengthen and coordinate eye muscles, worked equally well for people with head injuries.

The study participants were under the care of sports medicine physicians Christina Master, M.D., with the Minds Matter Concussion Program of Children’s Hospital of Philadelphia, and Arlene Goodman, M.D., with the Somerset Pediatric Group.

“Eye problems are the biggest issue in the majority of patients who have persistent symptoms after a concussion,” Goodman said.

She noted that the majority of her concussion patients have convergence insufficiency. Some of them recover within the first three weeks, but a significant number have persisting symptoms a month out. They are currently referred to physical therapy, and if they don’t respond, they follow up with vision therapy.

“There are few providers who offer this type of therapy, and it’s not covered by insurance. Some patients can’t afford to pay for it and therefore are left with persistent headaches and eye problems,” she said.

“As someone who treats patients with concussion and often am consulted for second or third opinions, what I have found both clinically and in my research is that vision deficits after concussion are often missed,” Master said.

“The American Academy of Pediatrics and the international Concussion in Sport Group recommend screening for vision disorders after concussion and the results of this study now provide very strong, high-quality evidence for recommending treatment with rehabilitation of the vision system to address these deficits.”

She added, “I am very optimistic that the results of the study will inform standardized treatment protocols for concussion-related CI and prompt third party reimbursement for this treatment, which would improve the quality of life for millions of people suffering from this disorder.”

While testing their patients’ vision, assessing their ability to perform daily tasks such as reading, and collecting eye movement data to determine how quickly and accurately they tracked a moving target on a computer screen, the group also examined links to the brain. Through fMRI imaging, they measured changes in blood oxygen levels in different regions of the brain to determine how much energy was produced, which is an indicator of eye performance, such as speed.

In addition to levels of blood oxygen, the team led by Suril Gohel, Ph.D. of Rutgers University and Farzin Hajebrahimi, Ph.D. of NJIT also measured how consistently neurons in the eye-functioning regions fired, whether cells near those neurons got recruited to help with tasks and whether connections between neurons improved so that signals flowed faster and more effectively.

Alvarez, principal investigator (PI) of the study, and Scheiman, the co-PI, will present their results at the annual meeting of the American Academy of Optometry in October. They were the first researchers to describe how CI-related vision therapy changed brain mechanisms, reducing symptoms.

Moving forward, Alvarez is designing a virtual reality vision therapy that tracks eye movements and can be performed at home on a computer. Physicians would receive scores to assist them in decisions about returning children to sports, school and other activities.

“Families have very hectic schedules, and it’s challenging for parents to bring their children for treatment twice a week. Many do not have the resources to pay for it. Furthermore, more remote areas may not even offer these specialized rehabilitative services,” she said.

“Using virtual reality technologies offers the potential for therapy to be done in the comfort of a patient’s home using an entertaining game which can improve patient compliance.”

Key Questions Answered:

A: Nearly half experience convergence or accommodation insufficiency, causing double or blurred vision, headaches, and concentration difficulties.

A: After 12 weeks of therapy, almost 90% of patients saw normal improvements versus less than 10% in those who just monitored symptoms.

A: It provides the first high-quality evidence that vision therapy not only restores sight but also changes brain mechanisms, supporting standardized treatment protocols.

About this concussion and vision research news

Author: Deric Raymond

Source: NJIT

Contact: Deric Raymond – NJIT

Image: The image is credited to Neuroscience News

Original Research: Open access.

“CONCUSS randomised clinical trial of vergence/accommodative therapy for concussion-related symptomatic convergence insufficiency” by Tara Alvarez et al. British Journal of Sports Medicine

Abstract

CONCUSS randomised clinical trial of vergence/accommodative therapy for concussion-related symptomatic convergence insufficiency

Objective

The CONCUSS randomised clinical trial compared the effectiveness of immediate office-based vergence/accommodative therapy with movement (OBVAM) to delayed therapy for the treatment of concussion-related convergence insufficiency (CONC-CI) in participants 11–25 years old with persisting postconcussive symptoms 4–24 weeks post injury.

Methods

Symptomatic CONC-CI was diagnosed using clinical signs via near point of convergence (NPC) and positive fusional vergence (PFV) and symptoms via the Convergence Insufficiency Symptom Survey (CISS). Participants were randomised to immediate OBVAM (twice weekly for 6 weeks) or delayed OBVAM (starting 6 weeks after baseline enrolment).

After 6 weeks (outcome time 1 assessment), the therapeutic outcomes of NPC, PFV and CISS were assessed and compared between the two groups. After the outcome time 1 assessment, the delayed group received twice-weekly OBVAM sessions for 8 weeks, while the immediate group received an additional 2 weeks of twice-weekly OBVAM sessions. The outcome time 2 assessment compared groups after each group received all 16 OBVAM sessions.

Results

In the immediate group, 46/52 (88%) were classified as successful or improved at the outcome time one assessment based on the primary outcome measure, a composite of NPC and PFV, compared with 4/52 (8%) in the delayed group (p<0.001).

The mean NPC decreased (improved) by 7.9 cm in the immediate group and 1.8 cm in the delayed group (mean difference at outcome time 1 assessment: 5.1 cm (95% CI: 3.9 to 6.3; p<0.001)). The mean PFV increased (improved) by 17.5Δ in the immediate group and 2.5∆ in the delayed group (mean difference at outcome time 1 assessment: 15.0∆ (95% CI:11.7 to 18.3); p<0.001).

At the outcome time 1 assessment, 41/52 (79%) of the participants in the immediate group had improved symptoms based on CISS scores ≤ preinjury scores or decreased by 10 points or more, compared with only 7/52 (13%) of participants from the delayed group (p<0.001).

When comparing dosing in the immediate group, for 12 OBVAM sessions, 88% were classified as successful or improved using the composite measurement of NPC and PFV, which increased to 94% after 16 OBVAM sessions. For the outcome time 2 assessment, when both groups had received 16 OBVAM sessions, no significant difference was observed for NPC, PFV or CISS (p=1.0).

Conclusion OBVAM therapy is effective in improving the NPC, PFV and symptoms in CONC-CI. Immediate initiation of OBVAM compared with delayed initiation shortens the period of symptoms experienced and fosters an earlier return to activities.

Trial registration number

clinicaltrials.gov identifier: NCT05262361.