A study, led by Royal Holloway University researcher Carolyn McGettigan, has identified the brain regions and interactions involved in impersonations and accents.

Using an fMRI scanner, the team asked participants, all non-professional impressionists, to repeatedly recite the opening lines of a familiar nursery rhyme either with their normal voice, by impersonating individuals, or by impersonating regional and foreign accents of English.

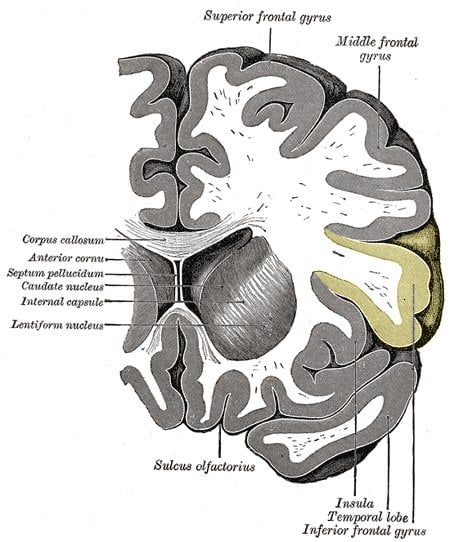

They found that when a voice is deliberately changed, it brings the left anterior insula and inferior frontal gyrus (LIFG) of the brain into play.

The researchers also discovered that when comparing impersonations against accents, areas in the posterior superior temporal/inferior parietal cortex and in the right middle/anterior superior temporal sulcus showed greater responses.

“The voice is a powerful channel for the expression of our identity – it conveys information such as gender, age and place of birth, but crucially, it also expresses who we want to be,” said lead author Carolyn McGettigan from the Department of Psychology at Royal Holloway University.

“Consider the difference between talking to a friend on the phone, talking to a police officer who’s cautioning you for parking violation, or speaking to a young infant. While the words we use might be different across these settings, another dramatic difference is the tone and style with which we deliver the words we say. We wanted to find out more about this process and how the brain controls it.”

While past work has found that listening to voices activates regions of the temporal lobe of the brain, no research had explored the brain regions involved in controlling vocal identity before this study.

“Our aim is to find out more about how the brain controls this very flexible communicative tool, which could potentially lead to new treatments for those looking to recover their own vocal identity following brain injury or a stroke, ” said Carolyn.

Notes about this neuroscience and impersonation research

Contact: Tanya Gubbay – Royal Holloway, University of London

Source: Royal Holloway, University of London press release

Image Source: The inferior frontal gyrus brain image is credited to Gray’s Anatomy and is in the public domain.

Original Research: Abstract for “T’ain’t What You Say, It’s the Way That You Say It—Left Insula and Inferior Frontal Cortex Work in Interaction with Superior Temporal Regions to Control the Performance of Vocal Impersonations ” by Carolyn McGettigan, Frank Eisner, Zarinah K. Agnew, Tom Manly, Duncan Wisbey and Sophie K. Scott in Journal of Cognitive Neuroscience. Published online May 22 2013 doi:10.1162/jocn_a_00427