Summary: Feeling Safe is a novel, effective treatment method that significantly reduces symptoms for those with persecutory delusions and paranoia.

Source: Oxford University

‘I was too paranoid about going out. Thinking someone’s going to stab me. I was housebound. Purely just paranoia. I missed out on so many things in life. I’d lie in bed, and I’d be thinking that tomorrow something’s going to happen, something’s going to happen. It would play on my mind 24/7.’

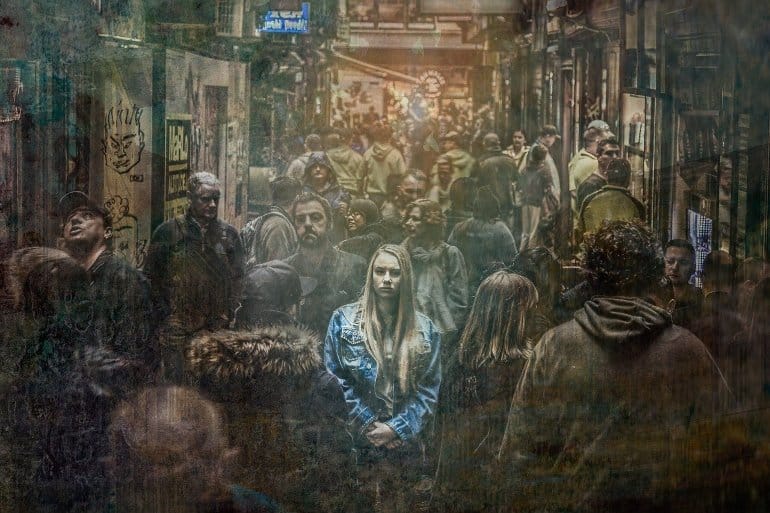

This fear of other people is common among people diagnosed with severe mental health disorders such as schizophrenia. Largely unfounded, often unrelenting, and wearyingly upsetting, these intensely paranoid thoughts are known as persecutory delusions. People feel very unsafe.

Also typical is the response: when being out and about is so frightening, staying at home can seem the only way to cope. But there are consequences for both mental and physical health. For example, three quarters of patients with severe paranoia have suicidal thoughts.

Life expectancy is on average 14.5 years shorter, due to conditions such as high blood pressure, diabetes and heart disease – illnesses to which inactivity is likely a significant contributory factor.

Given the distress caused by persecutory delusions, treatment is critically important. Usually, people are prescribed anti-psychotic medications. They certainly can help, but only about a quarter of patients have a good response. Moreover, these drugs can trigger unwelcome side-effects.

Sometimes medication is combined with psychological treatment – specifically something called cognitive behaviour therapy (CBT) for psychosis. Again, some people get real additional benefit, but all too often the paranoia persists.

There has been, then, plenty of scope for improvement in the treatment of persecutory delusions. So, I set myself an ambitious target: to produce a psychological therapy that would lead to recovery in persecutory delusions for 50% of patients for whom anti-psychotic medication had not succeeded. That half of patients would no longer believe that their fears were true.

The Feeling Safe programme, developed with colleagues over the past decade, is the result of that effort.

As you might imagine, developing Feeling Safe has been a long and eventful journey. First, we needed to develop a better understanding of the causes of persecutory delusions. Next, we built and evaluated brief interventions to tackle each of those causes. Finally, we combined those interventions into a new six-month-long treatment.

Patients were a crucial part of the design process. And we would not have got far without a succession of UK mental health funders – the National Institute for Health Research (NIHR), the Medical Research Council (MRC), and the Wellcome Trust – stepping up to the plate.

Let’s rewind to the first stage of the treatment development process. What are the causes of persecutory delusions? At the core of the delusion is a threat belief: a conviction that everyday situations are dangerous. Everyday situations have become associated with danger. That threat belief doesn’t appear out of the blue. It is triggered by real-life experiences (bullying, for example, or an assault).

But there is likely a genetic vulnerability at work too. Threat beliefs are sustained by what we call maintenance factors: for example, spending lots of time worrying, sleeping poorly, feeling inadequate, and avoiding the situations we fear.

Feeling Safe is fundamentally an effort to counteract and supersede memories of danger by helping the person to relearn that they are safe. To do that, we need to tackle first the key maintenance factors. We help people, for example, worry less, sleep better, and feel more self-confident. Then, ultimately, it’s about spending time in the feared situations with one’s defences lowered, fully engaged in the moment and experience. By so doing, the person can learn that they are, in fact, safe.

Does it work?

The results of the first randomised controlled clinical trial of Feeling Safe have just been published in the Lancet Psychiatry. Taking part were 130 patients with persistent persecutory delusions, recruited from NHS mental health services.

The form of the trial was intentionally tough: we compared the Feeling Safe Programme to an alternative psychological approach provided by the same therapists. In this way, we could tell if the Feeling Safe programme brings benefits beyond those that come with a positive therapeutic relationship.

Patients were assessed before treatment (which typically comprised twenty sessions over a six-month period), after treatment, and six months later.

The results have been as good as I had dared to imagine all those years back. Half of patients at the end of treatment no longer had a persecutory delusion. A further quarter experienced moderate benefit. And those gains largely remained at follow-up.

Feeling Safe did not only tackle paranoia; it also brought an improvement in patients’ general psychological wellbeing. Crucially, the treatment was very popular: almost everyone stayed the course. Feeling Safe showed large benefits compared to the alternative (and often effective) psychological treatment. The type of therapy we provide to patients really does matter.

Feeling Safe is the most effective psychological treatment for persecutory delusions. But the work does not stop there. The challenge now is to reach the many thousands of people whose lives have disrupted by severe paranoia, and not merely those being treated by our team.

We think too that the programme can be improved. Mindful of the quarter of trial participants who did not benefit from Feeling Safe, we will continue to explore alternative therapeutic strategies.

But we are optimistic that we are seeing a step change in the treatment of severe paranoia.

As the trial participant quoted at the beginning of this piece told us, ‘There are techniques taught that I will never forget. I feel very safe. After a life changing study for me, I feel very, very safe. I have a great life again. Genuinely, inside I feel very, very happy. I don’t have to worry anymore about people potentially attacking me. Living a safer life is more enjoyable.’

Funding: The study was funded by an NIHR Research Professorship awarded to Daniel Freeman (NIHR-RP-2014-05-003). It was also supported by the NIHR Oxford Health Biomedical Research Centre (BRC-1215-20005).

About this paranoia research news

Source: Oxford University

Contact: Press Office – Oxford University

Image: The image is in the public domain

Original Research: Open access.

“Comparison of a theoretically driven cognitive therapy (the Feeling Safe Programme) with befriending for the treatment of persistent persecutory delusions: a parallel, single-blind, randomised controlled trial” by Freeman, D., Emsley, R., Diamond, R., Collett, N., Bold, E., Chadwick, E., Isham, L., Bird, J., Edwards, D., Kingdon, D., Fitzpatrick, R., Kabir, T., Waite, F., & Oxford Cognitive Approaches to Psychosis Trial Study Group. Lancet Psychiatry

Abstract

Comparison of a theoretically driven cognitive therapy (the Feeling Safe Programme) with befriending for the treatment of persistent persecutory delusions: a parallel, single-blind, randomised controlled trial

Background

There is a large clinical need for improved treatments for patients with persecutory delusions. We aimed to test whether a new theoretically driven cognitive therapy (the Feeling Safe Programme) would lead to large reductions in persecutory delusions, above non-specific effects of therapy. We also aimed to test treatment effect mechanisms.

Methods

We did a parallel, single-blind, randomised controlled trial to test the Feeling Safe Programme against befriending with the same therapists for patients with persistent persecutory delusions in the context of non-affective psychosis diagnoses. Usual care continued throughout the duration of the trial.

The trial took place in community mental health services in three UK National Health Service trusts.

Participants were included if they were 16 years or older, had persecutory delusions (as defined by Freeman and Garety) for at least 3 months and held with at least 60% conviction, and had a primary diagnosis of non-affective psychosis from the referring clinical team.

Patients were randomly assigned to either the Feeling Safe Programme or the befriending programme, using a permuted blocks algorithm with randomly varying block size, stratified by therapist.

Trial assessors were masked to group allocation. If an allocation was unmasked then the unmasked assessor was replaced with a new masked assessor.

Outcomes were assessed at 0 months, 6 months (primary endpoint), and 12 months. The primary outcome was persecutory delusion conviction, assessed within the Psychotic Symptoms Rating Scale (PSYRATS; rated 0–100%). Outcome analyses were done in the intention-to-treat population. Each intervention was provided individually over 6 months.

This trial is registered with the ISRCTN registry, ISRCTN18705064.

Findings

From Feb 8, 2016, to July 26, 2019, 130 patients with persecutory delusions (78 [60%] men; 52 [40%] women, mean age 42 years [SD 12·1, range 17–71]; 86% White, 9% Black, 2% Indian; 2·3% Pakistani; 2% other) were recruited. 64 patients were randomly allocated to the Feeling Safe Programme and 66 patients to befriending.

Compared with befriending, the Feeling Safe Programme led to significant end of treatment reductions in delusional conviction (−10·69 [95% CI −19·75 to −1·63], p=0·021, Cohen’s d=–0·86) and delusion severity (PSYRATS, −2·94 [–4·58 to −1·31], p<0·0001, Cohen’s d=–1·20).

More adverse events occurred in the befriending group (68 unrelated adverse events reported in 20 [30%] participants) compared with the Feeling Safe group (53 unrelated adverse events reported in 16 [25%] participants).

Interpretation

The Feeling Safe Programme led to a significant reduction in persistent persecutory delusions compared with befriending. To our knowledge, these are the largest treatment effects seen for patients with persistent delusions. The principal limitation of our trial was the relatively small sample size when comparing two active treatments, meaning less precision in effect size estimates and lower power to detect moderate treatment differences in secondary outcomes.

Further research could be done to determine whether greater effects could be possible by reducing the hypothesised delusion maintenance mechanisms further. The Feeling Safe Programme could become the recommended psychological treatment in clinical services for persecutory delusions.

Funding

NIHR Research Professorship and NIHR Oxford Health Biomedical Research Centre.