Summary: Study reveals a correlation between instances of eye contact and higher levels of engagement during conversations.

Source: Dartmouth College

Making eye contact repeatedly when you’re talking to someone is common, but why do we do it? When two people are having a conversation, eye contact occurs during moments of “shared attention” when both people are engaged, with their pupils dilating in synchrony as a result, according to a Dartmouth study published in the Proceedings of the National Academy of Sciences.

“Eye contact is really immersive and powerful,” says lead author Sophie Wohltjen, a graduate student in psychological and brain sciences at Dartmouth.

“When two people are having a conversation, eye contact signals that shared attention is high —that they are in peak synchrony with one another. As eye contact persists, that synchrony then decreases. We think this is also good because too much synchrony can make a conversation stale. An engaging conversation requires at times being on the same page and at times saying something new. Eye contact seems to be one way we create a shared space while also allowing space for new ideas.”

“In the past, it has been assumed that eye contact creates synchrony, but our findings suggest that it’s not that simple,” says senior author Thalia Wheatley, a professor of psychological and brain sciences at Dartmouth, and principal investigator of the Dartmouth Social Systems Laboratory.

“We make eye contact when we are already in sync, and, if anything, eye contact seems to then help break that synchrony. Eye contact may usefully disrupt synchrony momentarily in order to allow for a new thought or idea.”

To examine the relationship between eye contact and pupillary synchrony in a natural conversation, pairs of Dartmouth students were brought into the lab. Wearing eye-tracking glasses and sitting across from each other, each pair was asked to have a conversation for 10 minutes, which was audio and video recorded. Participants could talk about whatever they wanted.

After the conversation was over, the two participants were separated into different rooms and were asked to watch the conversation that they just had and to continuously rate how engaged they were.

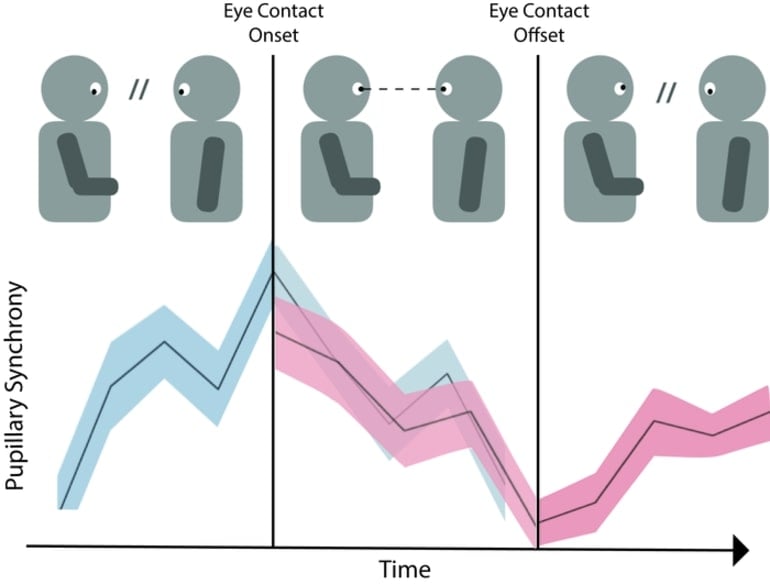

The research team looked at how pupillary synchrony increases and decreases around instances of eye contact. The results showed that people make eye contact as pupillary synchrony is at its peak. Pupillary synchrony then immediately decreases, only recovering again once eye contact is broken. The data also demonstrated a correlation between instances of eye contact and higher levels of engagement during the conversation.

“Conversation is a creative act in which people build a shared story from independent voices.” Wheatley adds, “Moments of eye contact seem to signal when we have achieved shared understanding and need to contribute our independent voice.”

The team’s results are consistent with other work, which has illustrated how periodically breaking synchrony can allow for creativity and individual exploration.

About this neuroscience research news

Author: Amy Olson

Source: Dartmouth College

Contact: Amy Olson – Dartmouth College

Image: The image is credited to Sophie Wohltjen

Original Research: Closed access.

“Eye contact marks the rise and fall of shared attention in conversation” by Sophie Wohltjen and Thalia Wheatley. PNAS

Abstract

Eye contact marks the rise and fall of shared attention in conversation

Conversation is the platform where minds meet: the venue where information is shared, ideas cocreated, cultural norms shaped, and social bonds forged. Its frequency and ease belie its complexity.

Every conversation weaves a unique shared narrative from the contributions of independent minds, requiring partners to flexibly move into and out of alignment as needed for conversation to both cohere and evolve. How two minds achieve this coordination is poorly understood.

Here we test whether eye contact, a common feature of conversation, predicts this coordination by measuring dyadic pupillary synchrony (a corollary of shared attention) during natural conversation.

We find that eye contact is positively correlated with synchrony as well as ratings of engagement by conversation partners. However, rather than elicit synchrony, eye contact commences as synchrony peaks and predicts its immediate and subsequent decline until eye contact breaks. This relationship suggests that eye contact signals when shared attention is high.

Furthermore, we speculate that eye contact may play a corrective role in disrupting shared attention (reducing synchrony) as needed to facilitate independent contributions to conversation.