Summary: Self-consciousness about one’s body affects the ability to learn and perform movement tasks, according to new research. Participants recalling body-related embarrassment performed worse on motor tasks compared to those recalling pride, with the negative impact being stronger in men than women.

The study highlights how focusing on body image shifts attention away from tasks, impairing performance, and emphasizes the need for supportive environments in sports. These findings could influence training approaches, sport culture, and broader domains like academics and well-being.

Key Facts:

- Body-related embarrassment negatively affects motor task performance, especially in men.

- Negative body image in sports can reduce participation and learning.

- Supportive coaching, less appearance-focused feedback, and mindful practices can help.

Source: University of Toronto

Self-consciousness about one’s body has a direct impact on the ability to learn and perform movement tasks, according to a new study by researchers from the University of Toronto’s Faculty of Kinesiology & Physical Education (KPE).

For the study, published in the journal Body Image, participants were asked to recall and write about a time when they felt either proud or embarrassed about their bodies, before completing a movement task.

“Overall, participants in the embarrassed group performed worse than the participants in the proud group, suggesting that evoking negative emotions about the body negatively impacted performance,” says Jude Bek, a post-doctoral fellow who co-authored the study with Professors Catherine Sabiston and Tim Welsh and PhD candidate Delaney Thibodeau.

The researchers also found that the negative impact of embarrassment was stronger among men than women; specifically, re-living body-related embarrassment showed great impact on movement time in men, and on task accuracy in women.

“I was surprised to see a stronger effect of embarrassment in the men, but it is possible that many women already have a heightened sense of body-related embarrassment, so this may have caused them to be less impacted by being asked to recall a time when they felt embarrassed about their body,” says Bek.

Sabiston says she, too, was surprised that embarrassment had a stronger effect in men than women. “For men, the requirement to re-live an embarrassing experience pertaining to their body may have elicited a stronger stress response and therefore greater attention bias that impacted motor performance,” Sabiston says, who holds a Canada Research Chair in Physical Activity and Mental Health

The study builds on previous work by Sabiston and Welsh aimed at testing the impact of body image factors on cognitive and motor performance outcomes. The main foundation of the work is that these emotions lead people to shift attention away from the task at hand to their appearance.

“If they are focused on their body, they are not focused on the task and therefore the performance on the task could be impaired,” says Sabiston, who worked with Welsh on a study that found that tight and revealing clothing negatively impacts motor performance compared to loose, concealing clothing.

“It is interesting to see emotions also having an impact on motor performance – such findings have been commonly observed in cognitive and academic tasks, but this is the first time it was shown in motor performance,” says Welsh.

“We believe this finding could have impacts on learning and life-long participation in sports and physical activity.”

Sabiston has carried out several studies that have shown that negative body image is related to drop-out from sports and physical activity due to decreased motivation to participate.

She says the sport world is “ripe with body-focused cues and stimuli” ranging from uniform fit and narratives of idealized athletic body types to teammate comparisons and spectator comments.

“Recent public discourse from the Olympics and Paralympic Games also show athletes are often the targets of body-focused stimuli,” she says.

The researchers hope their findings will lead coaches and trainers to reconsider how they provide feedback – if making athletes feel embarrassed leads to decreased performance and learning during training and competition, it might also affect their motivation to stay involved, potentially quelling the benefits of sport participation.

Sabiston says that coaches, parents and guardians are in the best position to make the change in sport culture through thoughtful and intentional communication that doesn’t focus on appearance, but rather on positive role modelling.

“Sport administrators can benefit from designing or allocating uniforms that de-emphasize the body shape and appearance and are comfortable, so they are not a constant focus for athletes,” she says.

“Administrators can also reduce appearance-focused media, like posters and print material, in training and performance centres.

“And, athletes can benefit from an awareness of the impact that these body-focused stimuli and cues have on their performance by proactively engaging in stress management and coping strategies such as motivational self-talk, mindfulness and self-compassion practices.”

While these findings have implications for sport skill development and competence, the researchers suggest they may go beyond sport to other important achievement-focused domains such as academics. They also say this study makes clear the need to continue to include men in research focused on body image.

Up next, the researchers intend to delve deeper into the broader implications of negative body image resulting from excessive body scrutiny in sport, including injury risk.

About this motor skills and body image research news

Author: Jelena Damjanovic

Source: University of Toronto

Contact: Jelena Damjanovic – University of Toronto

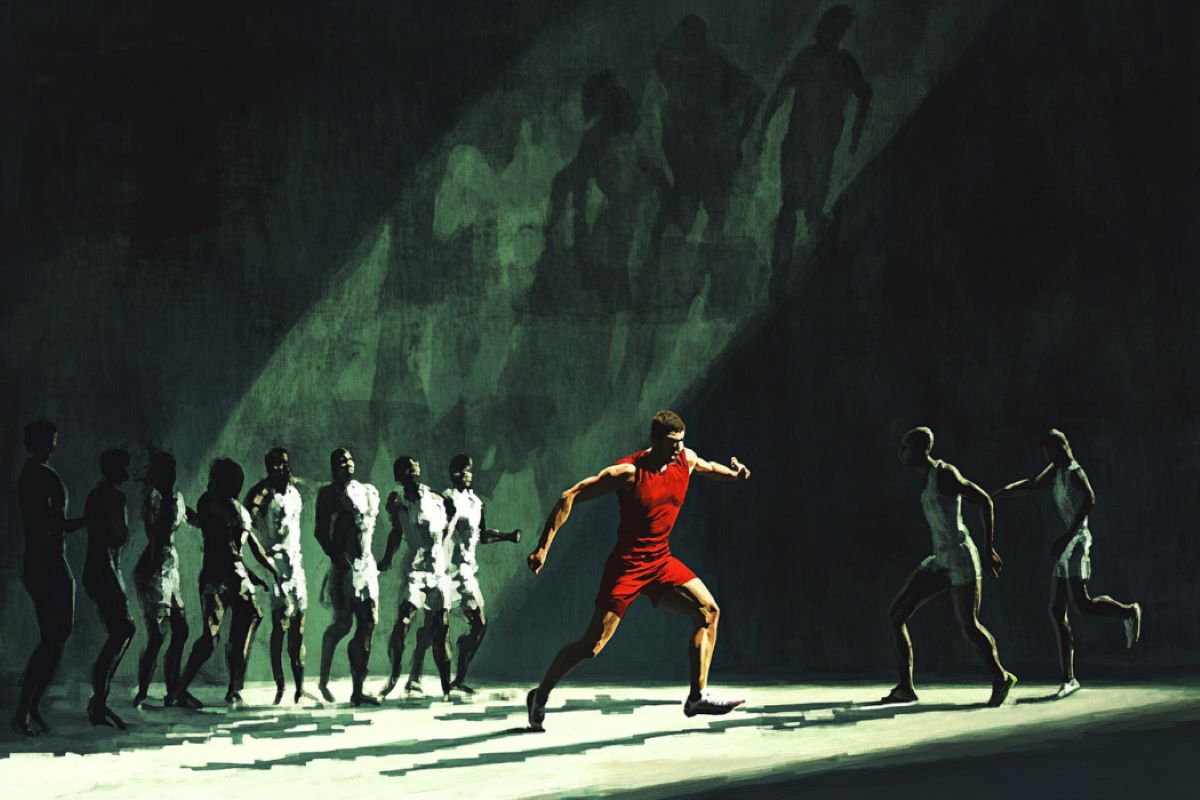

Image: The image is credited to Neuroscience News

Original Research: Open access.

“Gender-specific effects of self-objectification on visuomotor adaptation and learning” by Jude Bek et al. Body Image

Abstract

Gender-specific effects of self-objectification on visuomotor adaptation and learning

Self-objectification can influence cognitive and motor task performance by causing resources to be reallocated towards monitoring the body.

The present study investigated effects of recalling positive or negative body-related experiences on visuomotor adaptation in women and men. Moderating effects of positive and negative affect were also explored.

Participants (100 women, 47 men) were randomly assigned to complete a narrative writing task focused on body-related pride or embarrassment before performing a visuomotor adaptation (cursor rotation) task.

A retention test of the visuomotor task was completed after 24 h. Men in the embarrassment group were more impacted by the initial cursor rotation (in movement time and accuracy) than the pride group and showed poorer retention of movement time.

Women in the embarrassment group were less accurate than the pride group following initial rotation. In women only, affect modulated the effects of the negative recalled scenario.

Further analysis indicated that the differences between embarrassment and pride groups remained in a subset of participants (34 women, 28 men) who explicitly referred to their own movement within their recalled scenarios.

These results demonstrate that recalling body-related self-conscious emotions can impact visuomotor adaptation and learning in both women and men, but effects may differ between genders.