Summary: Researchers are making strides in restoring touch sensations to prosthetic limbs through brain stimulation. By using electrodes in the brain’s touch center, they can evoke stable, precise sensations, even allowing users to feel the shape and motion of objects.

This breakthrough could enable prosthetic users to perform tasks requiring fine motor control with confidence. Long-term tests show consistent sensation locations, critical for real-world usability.

Advanced stimulation patterns further enhance the tactile experience, mimicking natural touch. These innovations mark significant progress toward neuroprosthetics that improve quality of life for people with limb loss or sensory impairments.

Key Facts:

- Stable Sensations: Brain stimulation reliably evoked the same touch sensations over years, enhancing usability.

- Dynamic Touch: Patterns of stimulation allowed users to perceive motion and shapes, such as sliding objects or letters.

- Broad Applications: The approach could extend to restoring other types of sensory loss, including post-mastectomy touch.

Source: University of Chicago

You can probably complete an amazing number of tasks with your hands without looking at them. But if you put on gloves that muffle your sense of touch, many of those simple tasks become frustrating.

Take away proprioception — your ability to sense your body’s relative position and movement — and you might even end up breaking an object or injuring yourself.

“Most people don’t realize how often they rely on touch instead of vision — typing, walking, picking up a flimsy cup of water,” said Charles Greenspon, PhD, a neuroscientist at the University of Chicago.

“If you can’t feel, you have to constantly watch your hand while doing anything, and you still risk spilling, crushing or dropping objects.”

Greenspon and his research collaborators recently published papers in Nature Biomedical Engineering and Science documenting major progress on a technology designed to address precisely this problem: direct, carefully timed electrical stimulation of the brain that can recreate tactile feedback to give nuanced “feeling” to prosthetic hands.

The science of restoring sensation

These new studies build on years of collaboration among scientists and engineers at UChicago, the University of Pittsburgh, Northwestern University, Case Western Reserve University and Blackrock Neurotech.

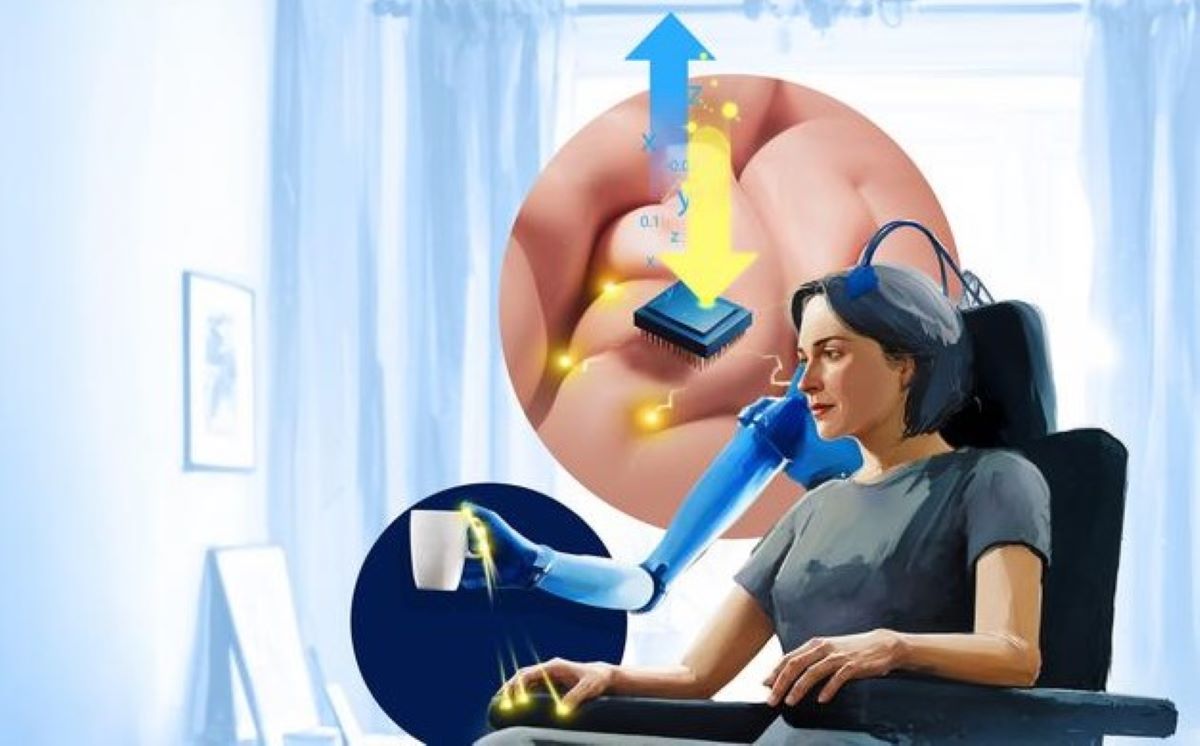

Together they are designing, building, implementing and refining brain-computer interfaces (BCIs) and robotic prosthetic arms aimed at restoring both motor control and sensation in people who have lost significant limb function.

On the UChicago side, the research was led by neuroscientist Sliman Bensmaia, PhD, until his unexpected passing in 2023.

The researchers’ approach to prosthetic sensation involves placing tiny electrode arrays in the parts of the brain responsible for moving and feeling the hand.

On one side, a participant can move a robotic arm by simply thinking about movement, and on the other side, sensors on that robotic limb can trigger pulses of electrical activity called intracortical microstimulation (ICMS) in the part of the brain dedicated to touch.

For about a decade, Greenspon explained, this stimulation of the touch center could only provide a simple sense of contact in different places on the hand.

“We could evoke the feeling that you were touching something, but it was mostly just an on/off signal, and often it was pretty weak and difficult to tell where on the hand contact occurred,” he said.

The newly published results mark important milestones in moving past these limitations.

Advancing understanding of artificial touch

In the first study, published in Nature Biomedical Engineering, Greenspon and his colleagues focused on ensuring that electrically evoked touch sensations are stable, accurately localized and strong enough to be useful for everyday tasks.

By delivering short pulses to individual electrodes in participants’ touch centers and having them report where and how strongly they felt each sensation, the researchers created detailed “maps” of brain areas that corresponded to specific parts of the hand.

The testing revealed that when two closely spaced electrodes are stimulated together, participants feel a stronger, clearer touch, which can improve their ability to locate and gauge pressure on the correct part of the hand.

The researchers also conducted exhaustive tests to confirm that the same electrode consistently creates a sensation corresponding to a specific location.

“If I stimulate an electrode on day one and a participant feels it on their thumb, we can test that same electrode on day 100, day 1,000, even many years later, and they still feel it in roughly the same spot,” said Greenspon, who was the lead author on this paper.

From a practical standpoint, any clinical device would need to be stable enough for a patient to rely on it in everyday life. An electrode that continually shifts its “touch location” or produces inconsistent sensations would be frustrating and require frequent recalibration.

By contrast, the long-term consistency this study revealed could allow prosthetic users to develop confidence in their motor control and sense of touch, much as they would in their natural limbs.

Adding feelings of movement and shapes

The complementary Science paper went a step further to make artificial touch even more immersive and intuitive. The project was led by first author Giacomo Valle, PhD, a former postdoctoral fellow at UChicago who is now continuing his bionics research at Chalmers University of Technology in Sweden.

“Two electrodes next to each other in the brain don’t create sensations that ‘tile’ the hand in neat little patches with one-to-one correspondence; instead, the sensory locations overlap,” explained Greenspon, who shared senior authorship of this paper with Bensmaia.

The researchers decided to test whether they could use this overlapping nature to create sensations that could let users feel the boundaries of an object or the motion of something sliding along their skin.

After identifying pairs or clusters of electrodes whose “touch zones” overlapped, the scientists activated them in carefully orchestrated patterns to generate sensations that progressed across the sensory map.

Participants described feeling a gentle gliding touch passing smoothly over their fingers, despite the stimulus being delivered in small, discrete steps.

The scientists attribute this result to the brain’s remarkable ability to stitch together sensory inputs and interpret them as coherent, moving experiences by “filling in” gaps in perception.

The approach of sequentially activating electrodes also significantly improved participants’ ability to distinguish complex tactile shapes and respond to changes in the objects they touched.

They could sometimes identify letters of the alphabet electrically “traced” on their fingertips, and they could use a bionic arm to steady a steering wheel when it began to slip through the hand.

These advancements help move bionic feedback closer to the precise, complex, adaptive abilities of natural touch, paving the way for prosthetics that enable confident handling of everyday objects and responses to shifting stimuli.

The future of neuroprosthetics

The researchers hope that as electrode designs and surgical methods continue to improve, the coverage across the hand will become even finer, enabling more lifelike feedback.

“We hope to integrate the results of these two studies into our robotics systems, where we have already shown that even simple stimulation strategies can improve people’s abilities to control robotic arms with their brains,” said co-author Robert Gaunt, PhD, associate professor of physical medicine and rehabilitation and lead of the stimulation work at the University of Pittsburgh.

Greenspon emphasized that the motivation behind this work is to enhance independence and quality of life for people living with limb loss or paralysis.

“We all care about the people in our lives who get injured and lose the use of a limb — this research is for them,” he said.

“This is how we restore touch to people. It’s the forefront of restorative neurotechnology, and we’re working to expand the approach to other regions of the brain.”

The approach also holds promise for people with other types of sensory loss. In fact, the group has also collaborated with surgeons and obstetricians at UChicago on the Bionic Breast Project, which aims to produce an implantable device that can restore the sense of touch after mastectomy.

Although many challenges remain, these latest studies offer evidence that the path to restoring touch is becoming clearer. With each new set of findings, researchers come closer to a future in which a prosthetic body part is not just a functional tool, but a way to experience the world.

About this neurotech and neuroprosthetics research news

Author: Grace Niewijk

Source: University of Chicago

Contact: Grace Niewijk – University of Chicago

Image: The image is credited to Chalmers University of Technology | Boid | David Ljungberg

Original Research: Closed access.

“Tactile edges and motion via patterned microstimulation of the human somatosensory cortex” by Giacomo Valle et al. Science

Open access.

“Evoking stable and precise tactile sensations via multi-electrode intracortical microstimulation of the somatosensory cortex” by Giacomo Valle et al. Nature Biomedical Engineering

Abstract

Tactile edges and motion via patterned microstimulation of the human somatosensory cortex

Intracortical microstimulation (ICMS) of somatosensory cortex evokes tactile sensations whose properties can be systematically manipulated by varying stimulation parameters. However, ICMS currently provides an imperfect sense of touch, limiting manual dexterity and tactile experience.

Leveraging our understanding of how tactile features are encoded in the primary somatosensory cortex (S1), we sought to inform individuals with paralysis about local geometry and apparent motion of objects on their skin.

We simultaneously delivered ICMS through electrodes with spatially patterned projected fields (PFs), evoking sensations of edges. We then created complex PFs that encode arbitrary tactile shapes and skin indentation patterns.

By delivering spatiotemporally patterned ICMS, we evoked sensation of motion across the skin, the speed and direction of which could be controlled. Thus, we improved individuals’ tactile experience and use of brain-controlled bionic hands.

Abstract

Evoking stable and precise tactile sensations via multi-electrode intracortical microstimulation of the somatosensory cortex

Tactile feedback from brain-controlled bionic hands can be partially restored via intracortical microstimulation (ICMS) of the primary somatosensory cortex.

In ICMS, the location of percepts depends on the electrode’s location and the percept intensity depends on the stimulation frequency and amplitude. Sensors on a bionic hand can thus be linked to somatotopically appropriate electrodes, and the contact force of each sensor can be used to determine the amplitude of a stimulus.

Here we report a systematic investigation of the localization and intensity of ICMS-evoked percepts in three participants with cervical spinal cord injury.

A retrospective analysis of projected fields showed that they were typically composed of a focal hotspot with diffuse borders, arrayed somatotopically in keeping with their underlying receptive fields and stable throughout the duration of the study.

When testing the participants’ ability to rapidly localize a single ICMS presentation, individual electrodes typically evoked only weak sensations, making object localization and discrimination difficult.

However, overlapping projected fields from multiple electrodes produced more localizable and intense sensations and allowed for a more precise use of a bionic hand.