Summary: New research suggests our brains prioritize actions based on rewards, not habits, challenging the idea that tech simply “steals” attention. The study found that when presented with multiple tasks, participants consistently chose the option with the highest reward, even if it conflicted with a trained habit.

This reward-driven attention helps explain why digital technology is so engaging; it taps into our natural preference for immediate, valuable rewards. Understanding how we choose actions in the moment could inform future studies on long-term planning, especially for actions tied to personal values. In essence, it’s not technology but our reward-seeking minds that drive attention shifts.

Key Facts:

- Reward-driven attention: People prioritize tasks with the highest perceived reward over habitual actions.

- Tech’s role: Digital tech doesn’t control attention but leverages our natural reward-seeking tendencies.

- Future research: Studies are planned to explore how we recall actions planned for the future.

Source: Univesity of Copenhagen

The mobile phone is often blamed for drowning us in information and stealing our attention. But it is rather our inner reward system that our phones and tech companies utilize, shows new research from the University of Copenhagen.

We often hear that we live in an attention economy, where tech companies like Google, Apple, and Facebook present us with an overwhelming amount of irresistible information that steals our attention.

This is not wrong, but our understanding of how attention works is imprecise. In a new study, researchers from the University of Copenhagen show that our attention works surprisingly well. And that it enables us to achieve exactly what our brains most desire—rewards.

In a series of controlled experiments that have just been published in the article “Testing Biased Competition Between Attention Shifts,” in the Journal of Experimental Psychology: Human Perception and Performance, the researchers have studied what causes people to turn their attention towards a particular action when they are presented with a number of different courses of action.

In the experiments, the choices were represented by a series of boxes on a computer screen, which could hold between 1 and 9 points. Each box was associated with a corner of the screen where a random letter was displayed. The task was then to report one of the letters and thus earn the points indicated by the box.

“The participants in our experiments were presented with four boxes at once and had to quickly shift their attention to one of the possibilities. They marked the attention shift by entering a letter, which was presented in the corner of the screen.

“The process had to be repeated thousands of times by each individual participant, so we could be certain that it was not a matter of chance,” explains Associate Professor Thor Grünbaum from the Cognition, Intention and Action research group, which he heads together with Professor Søren Kyllingsbæk.

“Our experiments show that the participants prepare several attention shifts at the same time. That is, several attention shifts compete simultaneously to be performed. By associating the different shifts with different rewards, we can show that the shift associated with the highest reward usually wins.

“The experiments therefore show that reward is a decisive factor in determining what we notice and remember to do when we are presented with multiple opportunities.”

Therefore, Grünbaum and Kyllingsbæk also believe that it is imprecise to talk about the digital world stealing or controlling our attention. It is almost the opposite. The technologies often exploit our ability to choose exactly the content that gives us the greatest reward when presented with a wide range of possibilities.

In other words, what tech companies leverage are our subjective values by rewarding our attention shifts and actions.

Habits versus rewards

Normally we think of habits as close to unbreakable, but here too the experiment can tell us something important.

“It tells us something about our behavior in a situation where we have been trained for a certain action. The participants in our experiments spent a lot of time learning how to connect a single box with a shift of attention to a particular corner of the screen.

“Training the attention shifts should make them into habits. When they are presented with four competing actions that they have a short time to decide on, we show that they choose the reward over the habitual behavior,” says Grünbaum.

In the experimental situation, the action with the highest subjective value is most likely to be selected, even though other actions have been trained extensively, conclude the authors.

This means that a person’s values compete with ingrained habits—a competition the habit often loses if another action is more important. This insight is also worth bringing into the discussion about attention economy.

Long-term planning

The next step for the researchers will be a project in which they will examine how we plan in the long term. The current experiment shows something about what activates our shift in attention in the short term, but what happens when we try to plan actions in the future?

“If I have now decided to buy flour on the way home from work, I have to save the action in my long-term memory. What we want to understand is how we go about recalling the things we set out to do. Especially when we have planned several different actions, which we typically do,” says Grünbaum.

Grünbaum and Kyllingsbæk expect that here too we will focus our attention on the action to which we attach the highest value. But when we are in the real world as opposed to a laboratory, other factors come into play.

“Previous research has shown that our surroundings play an important role in how we remember things. Therefore, one can imagine that my plan to buy flour will be activated if I see a supermarket sign on my way home from work. We are developing experimental designs to study the factors involved in the selection between competing plans.”

About this attention and neuroscience research news

Author: Thor Grünbaum

Source: University of Copenhagen

Contact: Thor Grünbaum – University of Copenhagen

Image: The image is credited to Neuroscience News

Original Research: Open access.

“Testing biased competition between attention shifts: The new multiple cue paradigm” by Thor Grünbaum et al. Journal of Experimental Psychology: Human Perception and Performance

Abstract

Testing biased competition between attention shifts: The new multiple cue paradigm

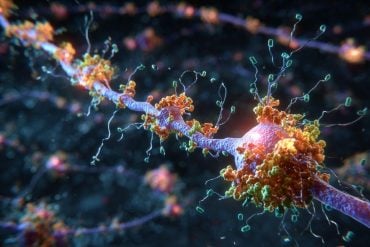

While the classic Posner cuing paradigm has been used to study cuing of a single endogenous shift of attention, we present a new multiple cue paradigm to study the competition between multiple endogenous shifts of attention.

The new paradigm enables us to manipulate the number of competing attention shifts and their relative importance.

In three experiments, we demonstrate that the process of selecting one among other relevant attention shifts is governed by limited capacity and biased competition.

We show that the probability of performing the most optimal attention shift is influenced by the total number of attention shifts competing for execution and that reward is a determining factor for the selection between attention shifts.

We explain our results with a recent mathematical model of biased selection of response sets (the model of intention selection [MIS]).

Our new paradigm offers a critical test of MIS and is an important new tool for investigating the mechanisms underlying the retrieval of response sets from long-term memory (LTM).

The model (MIS) and the new multiple cue paradigm can provide a new perspective on LTM representations of response sets for instrumental action and on habitual and goal-directed processing in action control.