Summary: A new study tested how humans and ChatGPT understand color metaphors, revealing key differences between lived experience and language-based AI. Surprisingly, colorblind and color-seeing humans showed similar comprehension, suggesting vision isn’t essential for interpreting metaphors.

Painters, however, outperformed others on novel metaphors, indicating that hands-on color experience deepens understanding. ChatGPT generated consistent, culture-informed answers but struggled with novel or inverted metaphors, highlighting the limits of language-only models in fully capturing human cognition.

Key Facts:

- Color Vision Not Required: Colorblind and color-seeing humans performed similarly in metaphor tasks.

- Experience Matters: Painters excelled at novel metaphors, suggesting practical experience enhances understanding.

- AI Limitations: ChatGPT mimicked human responses but faltered on novel and reversed metaphors.

Source: USC

ChatGPT works by analyzing vast amounts of text, identifying patterns and synthesizing them to generate responses to users’ prompts.

Color metaphors like “feeling blue” and “seeing red” are commonplace throughout the English language, and therefore comprise part of the dataset on which ChatGPT is trained.

But while ChatGPT has “read” billions of words about what it might mean to feel blue or see red, it has never actually seen a blue sky or a red apple in the ways that humans have.

Which begs the questions: Do embodied experiences — the capacity of the human visual system to perceive color — allow people to understand colorful language beyond the textual ways ChatGPT does? Or is language alone, for both AI and humans, sufficient to understand color metaphors?

New results from a study published in Cognitive Science led by Professor Lisa Aziz-Zadeh and a team of university and industry researchers offer some insights into those questions, and raise even more.

“ChatGPT uses an enormous amount of linguistic data to calculate probabilities and generate very human-like responses,” said Aziz-Zadeh, the publication’s senior author.

“But what we are interested in exploring is whether or not that’s still a form of secondhand knowledge, in comparison to human knowledge grounded in firsthand experiences.”

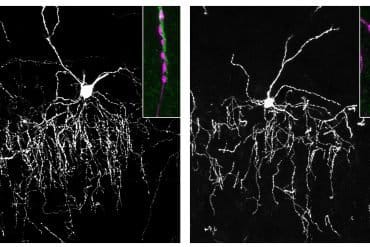

Aziz-Zadeh is the director of the USC Center for the Neuroscience of Embodied Cognition and holds a joint appointment at the USC Dornsife Brain and Creativity Institute. Her lab uses brain imaging techniques to examine how neuroanatomy and neurocognition are involved in higher order skills including language, thought, emotions, empathy and social communication.

The study’s interdisciplinary team included psychologists, neuroscientists, social scientists, computer scientists and astrophysicists from UC San Diego, Stanford, Université de Montréal, the University of the West of England and Google DeepMind, Google’s AI research company based in London.

A Google Faculty Gift to Aziz-Zadeh partially funded the study.

ChatGPT understands ‘very pink party’ better than ‘burgundy meeting’

The research team conducted large-scale online surveys comparing four participant groups: color-seeing adults, colorblind adults, painters who regularly work with color pigments, and ChatGPT. Each group was tasked with assigning colors to abstract words like physics. Groups were also asked to decipher familiar color metaphors (“they were on red alert”) and unfamiliar ones (“it was a very pink party”), and then to explain their reasoning.

Results show that color-seeing and colorblind humans were surprisingly similar in their color associations, suggesting that, contrary to the researchers’ hypothesis, visual perception is not necessarily a requirement for metaphorical understanding.

However, painters showed a significant boost in correctly interpreting novel color metaphors. This suggests that hands-on experiences using color unlocks deeper conceptual representations of it in language.

ChatGPT also generated highly consistent color associations, and when asked to explain its reasoning, often referenced emotional and cultural associations with various colors. For example, to explain the pink party metaphor, ChatGPT replied that “Pink is often associated with happiness, love, and kindness, which suggest that the party was filled with positive emotions and good vibes.”

However, ChatGPT used embodied explanations less frequently than humans did. It also broke down more often when prompted to interpret novel metaphors (“the meeting made him burgundy”) or invert color associations (“the opposite of green”).

As AI continues to evolve, studies like this underscore the limits of language-only models in representing the full range of human understanding. Future research may explore whether integrating sensory input — such as visual or tactile data — could help AI models move closer to approximating human cognition.

“This project shows that there’s still a difference between mimicking semantic patterns, and the spectrum of human capacity for drawing upon embodied, hands-on experiences in our reasoning,” Aziz-Zadeh said.

About this study:

In addition to Aziz-Zadeh’s Google Faculty Gift, this study was also supported by the Barbara and Gerson Bakar Faculty Fellowship and the Haas School of Business at the University of California, Berkeley. Google had no role in the study design, data collection, analysis or publication decisions.

About this AI and LLM research news

Author: Leigh Hopper

Source: USC

Contact: Leigh Hopper – USC

Image: The image is credited to Neuroscience News

Original Research: Closed access.

“Statistical or Embodied? Comparing Colorseeing, Colorblind, Painters, and Large Language Models in Their Processing of Color Metaphors” by Lisa Aziz-Zadeh et al. Cognitive Science

Abstract

Statistical or Embodied? Comparing Colorseeing, Colorblind, Painters, and Large Language Models in Their Processing of Color Metaphors

Can metaphorical reasoning involving embodied experience—such as color perception—be learned from the statistics of language alone?

Recent work finds that colorblind individuals robustly understand and reason abstractly about color, implying that color associations in everyday language might contribute to the metaphorical understanding of color.

However, it is unclear how much colorblind individuals’ understanding of color is driven by language versus their limited (but no less embodied) visual experience.

A more direct test of whether language supports the acquisition of humans’ understanding of color is whether large language models (LLMs)—those trained purely on text with no visual experience—can nevertheless learn to generate consistent and coherent metaphorical responses about color.

Here, we conduct preregistered surveys that compare colorseeing adults, colorblind adults, and LLMs in how they (1) associate colors to words that lack established color associations and (2) interpret conventional and novel color metaphors.

Colorblind and colorseeing adults exhibited highly similar and replicable color associations with novel words and abstract concepts.

Yet, while GPT (a popular LLM) also generated replicable color associations with impressive consistency, its associations departed considerably from colorseeing and colorblind participants.

Moreover, GPT frequently failed to generate coherent responses about its own metaphorical color associations when asked to invert its color associations or explain novel color metaphors in context.

Consistent with this view, painters who regularly work with color pigments were more likely than all other groups to understand novel color metaphors using embodied reasoning.

Thus, embodied experience may play an important role in metaphorical reasoning about color and the generation of conceptual connections between embodied associations.