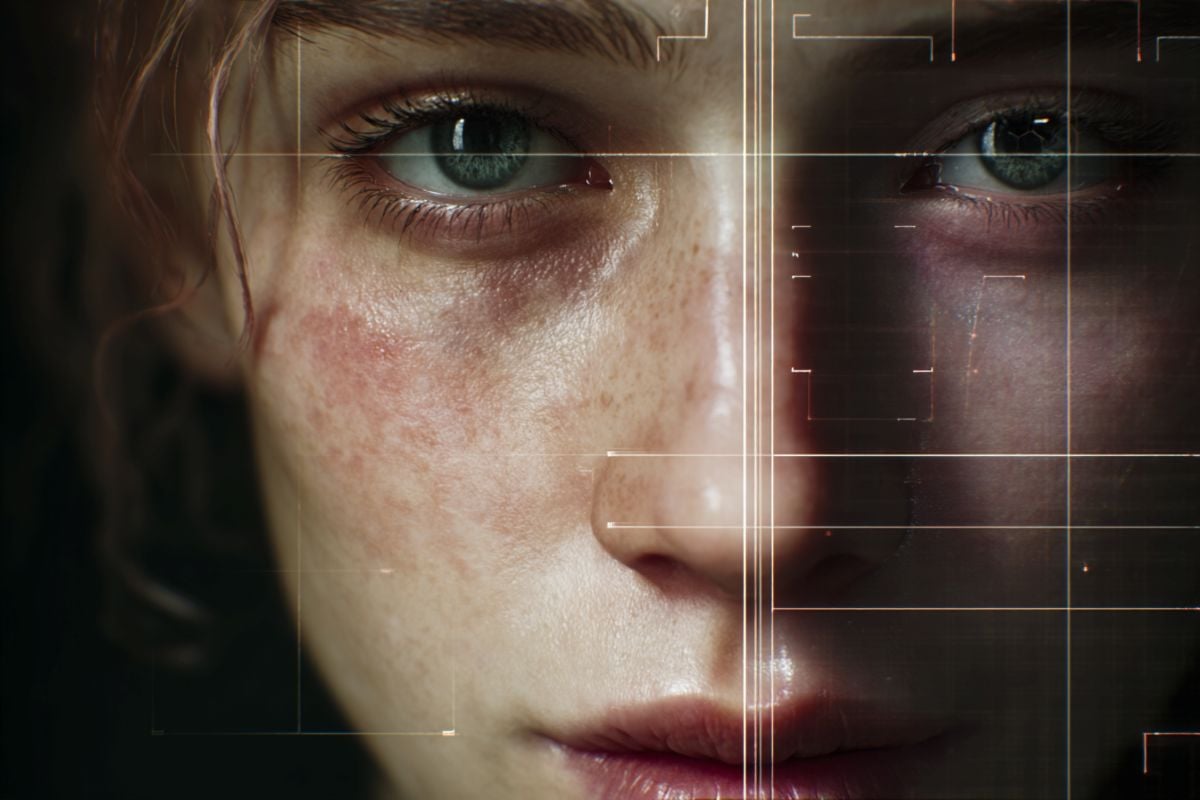

Summary: If you think you can “just tell” when a face is AI-generated, you’re likely overconfident—and potentially at risk. A new study from reveals that humans are now consistently fooled by the most advanced face-generation systems.

Even “super-recognisers”—people with a rare, natural gift for face identification—performed only marginally better than chance. Ironically, the study found that the biggest “tell” for an AI face isn’t a glitch or a distorted ear, but perfection itself. AI faces tend to be “too good to be true”: unusually symmetrical, well-proportioned, and statistically average.

Key Facts

- The Overconfidence Gap: Most people rely on outdated cues (distorted teeth, messy backgrounds) that modern AI has already corrected.

- Super-Recognisers Fooled: People who typically excel at recognizing human faces struggled almost as much as the general population when identifying synthetic faces.

- The “Too Average” Rule: AI-generated faces are often more symmetrical and “average” in their proportions than real human faces, which our brains mistakenly interpret as attractiveness and familiarity.

- Security Risks: This misplaced confidence makes individuals and organizations more vulnerable to scams, fraudulent LinkedIn profiles, and deepfake identities in recruitment or dating.

- Need for Scepticism: Researchers argue that because visual judgment is no longer reliable, we must move toward a healthy level of skepticism regarding all digital images.

Source: UNSW

Most people believe they can spot AI-generated faces, but that confidence is out of date, research from UNSW Sydney and the Australian National University (ANU) has demonstrated.

With AI-generated faces now almost impossible to distinguish from real ones, this misplaced confidence could make individuals and organisations more vulnerable to scammers, fraudsters and bad actors, the researchers warn.

“Up until now, people have been confident of their ability to spot a fake face,” says UNSW School of Psychology researcher Dr James Dunn. “But the faces created by the most advanced face-generation systems aren’t so easily detectable anymore.”

In a research paper published in the British Journal of Psychology, researchers from UNSW and the ANU recruited 125 participants – including 36 people with exceptional face-recognition ability, known as super recognisers, and 89 control participants – to complete an online test in which they were shown a series of faces and asked to judge whether each image was real or AI-generated. Obvious visual flaws were screened out beforehand.

“What we saw was that people with average face-recognition ability performed only slightly better than chance,” Dr Dunn says.

“And while super-recognisers performed better than other participants, it was only by a slim margin. What was consistent was people’s confidence in their ability to spot an AI-generated face – even when that confidence wasn’t matched by their actual performance.”

The end of artefacts

Much of that confidence comes from cues that used to work. Early AI-generated faces were often given away by obvious visual artefacts – distorted teeth, glasses that merged into faces, ears that didn’t quite attach properly, or strange backgrounds that bled into hair and skin.

But as face-generation systems have improved, those kinds of errors have become far less common. The most realistic outputs no longer show obvious flaws, leaving faces that look convincing at a glance, and far harder to judge using the cues people are familiar with.

“A lot of people think they can still tell the difference because they’ve played with popular AI tools like ChatGPT or DALL·E,” says ANU psychologist Dr Amy Dawel. “But those examples don’t reflect how realistic the most advanced face-generation systems have become, and relying on them can give people a false sense of confidence.”

What interested the researchers was how readily even super-recognisers were fooled. While this group did perform better on average, the advantage was modest, and their accuracy remained far below what they typically achieved when recognising real human faces.

There was also substantial overlap between groups, with some non-super-recognisers outperforming super-recognisers – demonstrating this is not simply an experts-versus-everyone-else problem.

Too good to be true

But if AI faces are this convincing, are there any tells we should be looking for?

“Ironically, the most advanced AI faces aren’t given away by what’s wrong with them, but by what’s too right,” Dr Dawel says. “Rather than obvious glitches, they tend to be unusually average – highly symmetrical, well-proportioned and statistically typical.”

Qualities such as symmetry and average proportions usually signal attractiveness and familiarity. But in the current study, they become a red flag for artificiality.

“It’s almost as if they’re too good to be true as faces,” Dr Dawel says.

What to do about it

Super-recognisers didn’t stand out the way they typically do in tests involving real human faces, showing only a modest advantage. What differentiated them was a greater sensitivity to the same qualities identified in the study – plausible, unusually average and highly symmetrical faces. Even so, their limited success suggests spotting AI faces is not a skill that can be easily trained or learned.

The findings also carry practical implications – as relying on visual judgement alone is no longer reliable. This matters in contexts ranging from social media and online dating to professional networking and recruitment, where people often assume they can ‘just tell’ when a profile picture looks fake. Misplaced confidence may leave individuals and organisations more vulnerable to scams, fake profiles and fabricated identities.

“There needs to be a healthy level of scepticism,” Dr Dunn says. “For a long time, we’ve been able to look at a photograph and assume we’re seeing a real person. That assumption is now being challenged.”

Rather than teaching people tricks to spot synthetic faces, the broader lesson is about updating assumptions. The visual rules many of us rely on were shaped by earlier, less sophisticated systems.

“As face-generation technology continues to improve, the gap between what looks plausible and what is real may widen – and recognising the limits of our own judgement will become increasingly important,” says Dr Dawel.

Looking ahead

Interestingly, Dr Dunn wonders whether the research team has stumbled upon a new kind of face recogniser.

“Our research has revealed that some people are already sleuths at spotting AI-faces, suggesting there may be ‘super-AI-face-detectors’ out there.

“We want to learn more about how these people are able to spot these fake faces, what clues they are using, and see if these strategies can be taught to the rest of us.”

- Good with faces? Visit the UNSW Face Test page where you can test your face recognition skills and see how well you can spot AI-faces.

Key Questions Answered:

A: About 2% of the population has an extraordinary ability to remember and identify faces, even those they saw only briefly years ago. While they are usually the gold standard for police work, even they are now being outpaced by AI realism.

A: Paradoxically, look for “perfection.” If a face looks mathematically average, perfectly symmetrical, and has no slight “human” imbalances, it’s actually more likely to be AI. Real human faces almost always have minor asymmetries.

A: We are hardwired to trust what we see. If we believe we are talking to a real person on a professional network or a dating app, we are much more likely to share sensitive information or fall for financial scams.

Editorial Notes:

- This article was edited by a Neuroscience News editor.

- Journal paper reviewed in full.

- Additional context added by our staff.

About this AI and facial recognition research news

Author: Lachlan Gilbert

Source: UNSW

Contact: Lachlan Gilbert – UNSW

Image: The image is credited to Neuroscience News

Original Research: Open access.

“Too Good to be True: Synthetic AI Faces are More Average than Real Faces and Super-recognisers Know It” by . British Journal of Psychology

DOI:10.1111/bjop.70063

Abstract

Too Good to be True: Synthetic AI Faces are More Average than Real Faces and Super-recognisers Know It

The AI revolution has produced synthetic faces that often appear more human than photos of real people.

We tested whether individual differences in human face recognition ability explain variation in discriminating AI from real faces. Super-recognizers – people with exceptional ability to recognize human faces (N = 36) – outperformed a typical sample by 15% and by 7% compared to a group of higher performing, motivated control participants (Cohen’s d = 0.55; N = 89).

Individual difference analysis revealed that this pattern reflected a positive association between human face recognition and AI face discrimination abilities. AI discrimination ability was also associated with individuals’ sensitivity to the ‘hyper-average’ appearance of AI faces.

Deep neural networks optimized for face identity processing confirmed a more central distribution of AI faces in face-space. Moreover, centrality was associated with a higher probability of super-recognizers judging the faces as AI, but this pattern was not observed for controls.

Super-recognizers’ correct interpretation of hyper-averageness as a cue to artificiality constitutes the first mechanistic link between evolved expertise in face processing and AI face detection and addresses a common misconception regarding the structure of human face space.