Summary: If we can recognize the accent we hear, our brains are able to process foreign accented speech with better real time accuracy, a new study reports.

Source: Penn State.

Our brains process foreign-accented speech with better real-time accuracy if we can identify the accent we hear, according to a team of neurolinguists.

“Increased familiarity with an accent leads to better sentence processing,” said Janet van Hell, professor of psychology and linguistics and co-director of the Center for Language Science, Penn State. “As you build up experience with foreign-accented speech, you train your acoustic system to better process the accented speech.”

A native of the Netherlands, where the majority of people are bilingual in Dutch and English, van Hell noticed that her spoken interactions with people changed somewhat when she moved to central Pennsylvania.

“My speaker identity changed,” said van Hell. “I suddenly had a foreign accent, and I noticed that people were hearing me differently, that my interactions with people had changed because of my foreign accent. And I wanted to know why that is, scientifically.”

Van Hell and her colleague Sarah Grey, former Penn State postdoctoral researcher and now assistant professor of modern languages and literature at Fordham University, compared how people process foreign-accented and native-accented speech in a neurocognitive research study that measured neural signals associated with comprehension while listening to spoken sentences.

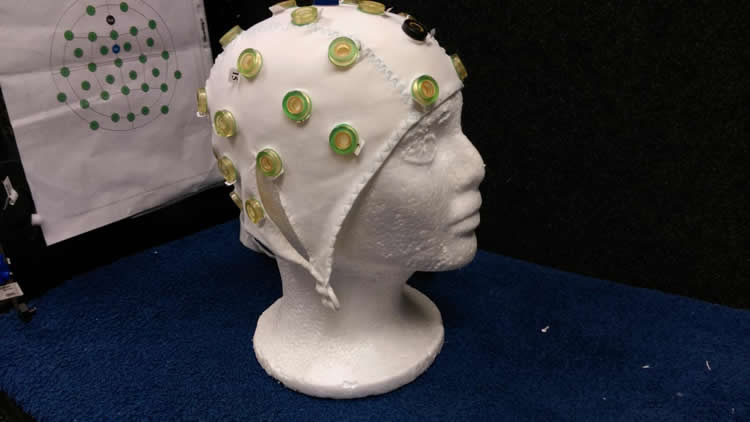

The researchers had study participants listen to the sentences while they recorded brain activity through an electroencephalogram. They then asked listeners to indicate whether they heard grammar or vocabulary errors after each sentence, to judge overall sentence comprehension.

The listeners heard sentences spoken in both a neutral American-English accent and a Chinese-English accent. Thirty-nine college-aged, monolingual, native English speakers with little exposure to foreign accents participated in this study.

The researchers tested grammar comprehension using personal pronouns, which are missing from the Chinese language, in sentences like “Thomas was planning to attend the meeting but she missed the bus to school.”

They tested vocabulary usage by substituting words far apart in meaning into simple sentences, such as using “cactus” in place of “airplane,” in sentences like “Kaitlyn traveled across the ocean in a cactus to attend the conference.”

The listeners were able to correctly identify both grammar and vocabulary errors in the American- and Chinese-accented speech at a similarly high level on a behavioral accuracy task, an average of 90 percent accuracy for both accents.

However, while average accuracy was high, Grey and van Hell found that the listeners’ brain responses differed between the two accents. In particular, the frontal negativity and N400 responses — features of an EEG signal related to speech processing — were different when processing errors in foreign- and native-accented sentences.

In a more detailed follow-up analysis, Grey and van Hell tried to explain these differences by connecting the EEG scans with a questionnaire asking listeners to identify the accents they heard.

When relating the EEG activity to the questionnaire responses, the researchers found that listeners who correctly identified the accent as Chinese-English responded to both grammar and vocabulary errors and had the same responses for both foreign and native accents.

Conversely, listeners who could not correctly identify the Chinese-English accent only responded to vocabulary errors, but not grammar errors, when made in foreign-accented speech. Native-accented speech produced responses for both types of error. The researchers published their results in the Journal of Neurolinguistics.

Van Hell plans to expand on these results by also studying how our brains process differences in regional accents and dialects in our native language, looking specifically at dialects across Appalachia, and how we process foreign-accented speech while living in a foreign-speaking country.

The results of this study are relevant in the United States, van Hell argues, where many people are second-language speakers or listen to second-language speakers on a daily basis. But exposure to foreign-accented speech can vary widely based on local population density and educational resources.

The world is becoming more global, she adds, and it is time to learn how our brains process foreign-accented speech and learn more about fundamental neurocognitive mechanisms of foreign-accented speech recognition.

“At first you might be surprised or startled by foreign-accented speech,” van Hell said, “but your neurocognitive system is able to adjust quickly with just a little practice, the same as identifying speech in a loud room. Our brains are much more flexible than we give them credit for.”

Funding: The National Science Foundation funded this research.

Source: A’ndrea Elyse Messer – Penn State

Image Source: NeuroscienceNews.com image is credited to Kimberly Cartier.

Original Research: Abstract for “Foreign-accented speaker identity affects neural correlates of language comprehension” by Sarah Grey, and Janet G. van Hell in Journal of Neurolinguistics. Published online April 2017 doi:10.1016/j.jneuroling.2016.12.001

[cbtabs][cbtab title=”MLA”]Penn State “Recognizing Foreign Accents Helps Brain Process Accented Speech: Brain Views Immoral Acts As If They Are Impossible.” NeuroscienceNews. NeuroscienceNews, 20 April 2017.

<https://neurosciencenews.com/accented-speech-neuroscience-6456/>.[/cbtab][cbtab title=”APA”]Penn State (2017, April 20). Recognizing Foreign Accents Helps Brain Process Accented Speech: Brain Views Immoral Acts As If They Are Impossible. NeuroscienceNew. Retrieved April 20, 2017 from https://neurosciencenews.com/accented-speech-neuroscience-6456/[/cbtab][cbtab title=”Chicago”]Penn State “Recognizing Foreign Accents Helps Brain Process Accented Speech: Brain Views Immoral Acts As If They Are Impossible.” https://neurosciencenews.com/accented-speech-neuroscience-6456/ (accessed April 20, 2017).[/cbtab][/cbtabs]

Abstract

Foreign-accented speaker identity affects neural correlates of language comprehension

This study tested semantic and grammatical processing of native- and foreign-accented speech. Monolinguals with little experience with foreign-accented speech listened to sentences spoken by foreign-accented and native-accented speakers while their brain activity was recorded using EEG/ERPs. We gathered behavioral measures of sentence comprehension, language attitudes, and accent perception. Behavioral results showed that listeners were highly accurate in comprehending both native- and foreign-accented sentences. ERP results showed that grammatical and semantic violations elicited different neural responses in native versus foreign accented speech. Native-accented speech elicited a frontal negativity (Nref) for grammatical violations and a robust N400 for semantic violations. However, in foreign-accented speech only semantic (not grammatical) violations elicited an ERP effect, a late negativity. Closer inspection of listeners who did and who did not correctly identify the foreign accent revealed that listeners who identified the foreign accent showed ERP responses for both grammatical and semantic errors: an N400-like effect to grammatical errors and a late negativity to semantic errors. In contrast, listeners who did not correctly identify the foreign accent showed no ERP responses to grammatical errors in the foreign-accented condition, but did show a late negativity to semantic errors. These findings provide novel insights into understanding the effects of listener experience and foreign-accented speaker identity on the neural correlates of language processing.

“Foreign-accented speaker identity affects neural correlates of language comprehension” by Sarah Grey, and Janet G. van Hell in Journal of Neurolinguistics. Published online April 2017 doi:10.1016/j.jneuroling.2016.12.001