The brain’s plasticity and its adaptability to new situations do not function the way researchers previously thought, according to a new study published in the journal Cell. Earlier theories are based on laboratory animals, but now researchers at Karolinska Institutet in Sweden have studied the human brain. The results show that a type of support cell, the oligodendrocyte, which plays an important role in the cell-cell communication in the nervous system, is more sophisticated in humans than in rats and mice – a fact that may contribute to the superior plasticity of the human brain.

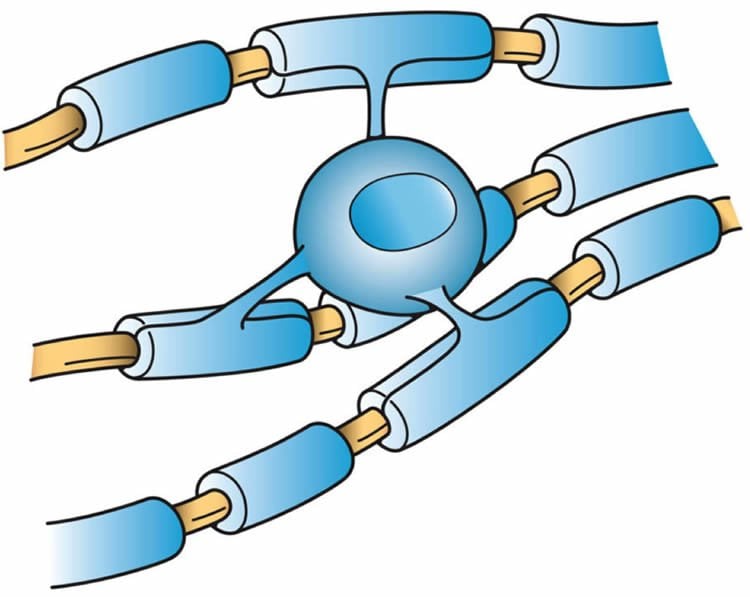

The learning process takes place partly by nerve cells creating new connections in the brain. Our nerve cells are therefore crucial for how we store new knowledge. But it is also important that nerve impulses travel at high speed and a special material called myelin plays a vital role. Myelin acts as an insulating layer around nerve fibres, the axons, and large quantities of myelin speed up the nerve impulses and improve function. When we learn something new, myelin production increases in the part of the brain where learning occurs. This interplay, where the brain’s development is shaped by the demands that are imposed on it, is what we know today as the brain’s plasticity.

Myelin is made by cells known as oligodendrocytes. In the last few years, there has been significant interest in oligodendrocytes and numerous studies have been conducted on mice and rats. These studies have shown that when the nerve cells of laboratory animals need more myelin, the oligodendrocytes are replaced. This is why researchers have assumed that the same also applies in humans. Researchers at Karolinska Institutet and their international collaborators have shown that this is not the case. In humans, oligodendrocyte generation is very low but despite this, myelin production can be modulated and increased if necessary. In other words, the human brain appears to have a preparedness for it, while in mice and rats, increased myelin production relies on the generation of new oligodendrocytes.

In the study in question, researchers have studied the brains of 55 deceased people in the age range from under 1 to 92 years. They were able to establish that at birth most oligodendrocytes are immature. They subsequently mature at a rapid rate until the age of five, when most reach maturity. After this, the turnover rate is very low. Only one in 300 oligodendrocytes are replaced per year, which means that we keep most of these cells our whole lives. This was apparent when the researchers carbon-dated the deceased people’s cells. The levels of carbon-14 isotopes rose sharply in the atmosphere after the nuclear weapons tests during the Cold War, and they provided a date mark in the cells. By studying carbon-14 levels in the oligodendrocytes, researchers have been able to determine their age.

“We were surprised by this discovery. In humans, the existing oligodendrocytes modulate their myelin production, instead of replacing the cells as in mice. It is probably what enables us to adapt and learn faster. Production of myelin is vital in several neurological diseases such as MS. We now have new basic knowledge to build upon,” says Jonas Frisén, PhD, Professor of Stem Cell Research at the Department of Cell and Molecular Biology at Karolinska Institutet.

About this neuroscience research

Contact: Press Office – Karolinska Institutet

Source: Karolinska Institutet press release

Image Source: The image is credited to Holly Fischer and is licensed Creative Commons Attribution 3.0 Unported

Original Research: Abstract for “Dynamics of Oligodendrocyte Generation and Myelination in the Human Brain” by Maggie S.Y. Yeung, Sofia Zdunek, Olaf Bergmann, Samuel Bernard, Mehran Salehpour, Kanar Alkass, Shira Perl, John Tisdale, Göran Possnert, Lou Brundin, Henrik Druid, and Jonas Frisén in Cell. Published online November 6 2014 doi:10.1016/j.cell.2014.10.011