Summary: A small, preliminary study helps researchers identify a region of the brain that specializes in the processing of auditory words.

Source: Northwestern University

Patients in a new Northwestern Medicine study were able to comprehend words that were written but not said aloud. They could write the names of things they saw but not verbalize them.

Even though these patients could hear and speak perfectly fine, a disease had crept into a portion of their brain that kept them from processing auditory words while still allowing them to process visual ones. Patients in the study had primary progressive aphasia (PPA), a rare type of dementia that destroys language and currently has no treatment.

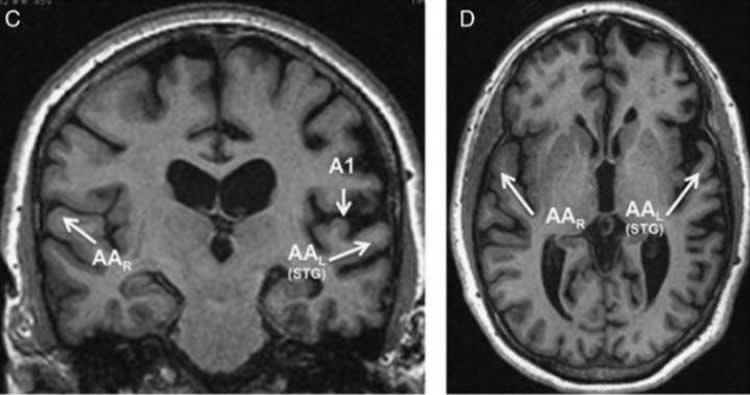

The study, published March 21 in the journal Cognitive and Behavioral Neurology, allowed the scientists to identify a previously little-studied area in the left brain that seems specialized to process auditory words.

If a patient in the study saw the word “hippopotamus” written on a piece of paper, they could identify a hippopotamus in flashcards. But when that patient heard someone say “hippopotamus,” they could not point to the picture of the animal.

“They had trouble naming it aloud but did not have trouble with visual cues,” said senior author Sandra Weintraub, professor of psychiatry and behavioral sciences and neurology at Northwestern University Feinberg School of Medicine. “We always think of these degenerative diseases as causing widespread impairment, but in early stages, we’re learning that neurodegenerative disease can be selective with which areas of the brain it attacks.”

For most patients with PPA, communicating can be difficult because it disrupts both the auditory and visual processes in the brain.

“It’s typically very frustrating for patients with PPA and their families,” said Weintraub, also a member of Northwestern’s Mesulam Center for Cognitive Neurology and Alzheimer’s Disease. “The person looks fine, they’re not limping and yet they’re a different person. It means having to re-adjust to this person and learning new ways to communicate.”

Remarkably, all four patients in this study could still communicate with others through writing and reading because of a specific type of brain pathology, TDP-43 Type A.

“It doesn’t happen that often that you just get an impairment in one area,” Weintraub said, explaining that the brain is compartmentalized so that different networks share the job of seemingly easy tasks, such as reading a word and being able to say it aloud. “The fact that only the auditory words were impaired in these patients and their visual words were untouched leads us to believe we’ve identified a new area of the brain where raw sound information is transformed into auditory word images.”

The findings are preliminary because of the small sample size but the scientists hope they will prompt more testing of this type of impairment in future PPA patients, and help design therapies for PPA patients that focus on written communication over oral communication.

While 30 percent of PPA cases are caused by molecular changes in the brain due to Alzheimer’s Disease, the most common cause of this dementia, especially in people under 60 years old, is frontotemporal lobar degeneration (FTLD). The patients in this study had FTLD-TDP Type A, which is very rare. The fact that this rare neurodegenerative disease is associated with a unique clinical disorder of language is a novel finding.

The study followed patients longitudinally and examined their brains postmortem. Weintraub stressed the importance of people participating in longitudinal brain studies while they’re alive and donating their brain to science after they die so the science community can continue learning more about how to keep brains healthy.

“We know so much about the heart, liver, kidneys, eyes and other organs but we know so little about the brain in comparison,” Weintraub said.

Funding: The study was supported in part by the National Institute on Deafness and Other Communication Disorders grant RO1 008552; the National Institute on Aging grant AG13854; and the National Institute of Neurological Disorders and Stroke grants R35 NS097261 and T32 NS047987.

The study’s first author is Dr. Marek-Marsel Mesulam, director of the Mesulam Center for Cognitive Neurology and Alzheimer’s Disease, professor of neurology at Feinberg and a neurologist at Northwestern Memorial Hospital. Robert S. Hurley and Dr. Eileen H. Bigio from Northwestern are also co-authors.

Source:

Northwestern University

Media Contacts:

Kristin Samuelson – Northwestern University

Image Source:

The image is credited to Northwestern University.

Original Research: Closed access

“Preferential Disruption of Auditory Word Representations in Primary Progressive Aphasia With the Neuropathology of FTLD-TDP Type A”

Mesulam, Marek-Marsel; Nelson, Matthew J.; Hyun, JungMoon; Rader, Benjamin; Hurley, Robert S.; Rademakers, Rosa; Baker, Matthew C.; Bigio, Eileen H.; Weintraub, Sandra Less

Cognitive and Behavioral Neurology. 32(1):46-53, March 2019. doi:10.1097/WNN.0000000000000180

Abstract

Preferential Disruption of Auditory Word Representations in Primary Progressive Aphasia With the Neuropathology of FTLD-TDP Type A

Four patients with primary progressive aphasia displayed a greater deficit in understanding words they heard than words they read, and a further deficiency in naming objects orally rather than in writing. All four had frontotemporal lobar degeneration-transactive response DNA binding protein Type A neuropathology, three determined postmortem and one surmised on the basis of granulin gene (GRN) mutation. These features of language impairment are not characteristic of any currently recognized primary progressive aphasia variant. They can be operationalized as manifestations of dysfunction centered on a putative auditory word-form area located in the superior temporal gyrus of the left hemisphere. The small size of our sample makes the conclusions related to underlying pathology and auditory word-form area dysfunction tentative. Nonetheless, a deeper assessment of such patients may clarify the nature of pathways that link modality-specific word-form information to the associations that mediate their recognition as concepts. From a practical point of view, the identification of these features in patients with primary progressive aphasia should help in the design of therapeutic interventions where written communication modalities are promoted to circumvent some of the oral communication deficits.