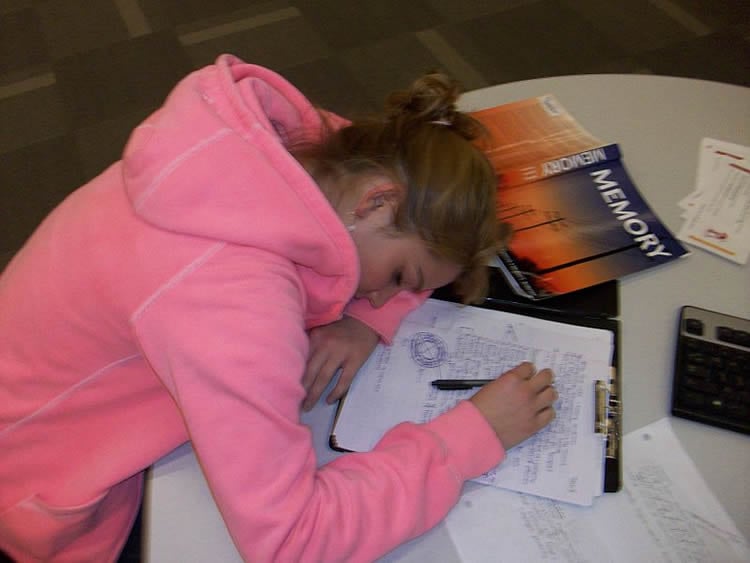

Researchers from Royal Holloway, University of London have found that successful long-term learning happens after classroom teaching, after the learners have slept on the new material.

Academics from the Department of Psychology at Royal Holloway taught a group of people new words from a fictional language, which unknown to them, was characterised by a rule relating the new words to one another. They found that although learners became aware of the rule within the new language shortly after being taught it, they were unable to apply it to understanding new, untrained words until after a period of rest.

Kathy Rastle, Professor of Cognitive Psychology at Royal Holloway, said: “Teachers have long suspected that proper rest is critical for successful learning. Our research provides some experimental support for this notion. Participants in our experiments were able to identify the hidden rule shortly after learning. However, it was not until they were tested a week after training that participants were able to use that rule to understand a totally new word from the fictional language when it was presented in a sentence.”

She added: “This result shows that the key processes that underpin long-term learning of general knowledge arise outside of the classroom, sometime after learning, and may be associated with brain processes that arise during sleep.”

The research, published in the journal Cognitive Psychology also found that participants needed time to consolidate this rule-based knowledge before being introduced to new words that did not follow the rule. If the exceptions were introduced during the initial vocabulary learning session, learners were unable to develop an understanding of the general rule.

The findings have important implications for language teaching in the classroom. It is not uncommon for teachers to introduce ‘tricky words’ or exceptions to the rule alongside rule-based examples when teaching children how to read phonetically. For example, children may be taught that that the rule for pronouncing CH applies to church, chest, and chess, but not to chef or chorus.

The research suggests exceptions should not be introduced until children have already consolidated the standard rule after a good night’s sleep, otherwise, they will not develop the necessary knowledge required.

Professor Rastle explains: “Our research suggests that including such exceptions at the time of initial learning could block the formation of general knowledge about the rule being taught. If we want learners to extract general principles from a set of examples, we need to think carefully about the structure of that set of examples.”

Funding: Open Access funded by Economic and Social Research Council.

Source: Royal Holloway, University of London

Image Source: The image is credited to Psy3330 W10 and is licensed Creative Commons Attribution-ShareAlike 3.0 Unported

Original Research: Full open access research for “From specific examples to general knowledge in language learning” by Jakke Tamminen, Matthew H. Davis, and Kathleen Rastle in Cognitive Psychology. Published online April 16 2015 doi:10.1016/j.cogpsych.2015.03.003

Abstract

From specific examples to general knowledge in language learning

The extraction of general knowledge from individual episodes is critical if we are to learn new knowledge or abilities. Here we uncover some of the key cognitive mechanisms that characterise this process in the domain of language learning. In five experiments adult participants learned new morphological units embedded in fictitious words created by attaching new affixes (e.g., -afe) to familiar word stems (e.g., “sleepafe is a participant in a study about the effects of sleep”). Participants’ ability to generalise semantic knowledge about the affixes was tested using tasks requiring the comprehension and production of novel words containing a trained affix (e.g., sailafe). We manipulated the delay between training and test (Experiment 1), the number of unique exemplars provided for each affix during training (Experiment 2), and the consistency of the form-to-meaning mapping of the affixes (Experiments 3–5). In a task where speeded online language processing is required (semantic priming), generalisation was achieved only after a memory consolidation opportunity following training, and only if the training included a sufficient number of unique exemplars. Semantic inconsistency disrupted speeded generalisation unless consolidation was allowed to operate on one of the two affix-meanings before introducing inconsistencies. In contrast, in tasks that required slow, deliberate reasoning, generalisation could be achieved largely irrespective of the above constraints. These findings point to two different mechanisms of generalisation that have different cognitive demands and rely on different types of memory representations.

“From specific examples to general knowledge in language learning” by Jakke Tamminen, Matthew H. Davis, and Kathleen Rastle in Cognitive Psychology. Published online April 16 2015 doi:10.1016/j.cogpsych.2015.03.003