Summary: A rapid memory system transition from the hippocampus to the posterior parietal cortex is stabilized as we sleep. Sleep and repeated rehearsal of memory jointly contribute to long-term memory consolidation.

Source: University of Tübingen

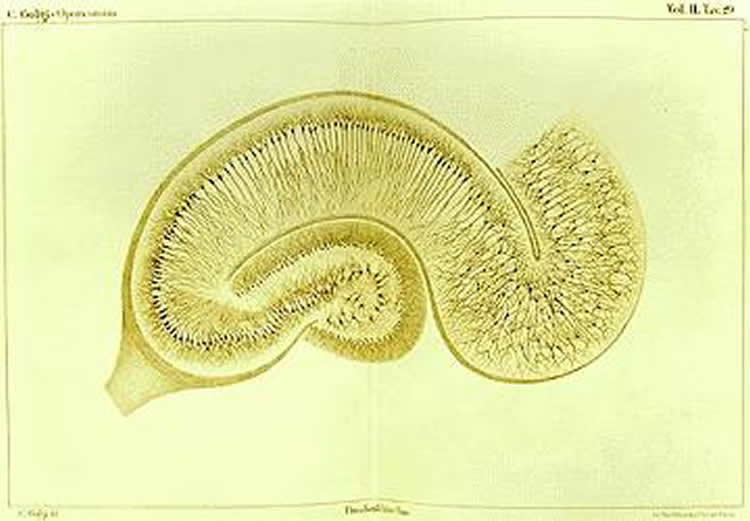

Two regions of our brain are used to store memory contents: the hippocampus and the cerebral cortex. While the former is required, especially at short notice, to absorb new information, the latter can store large amounts of information for a long time. Lea Himmer, dr. Monika Schönauer and Professor Steffen Gais from the Institute of Medical Psychology and Behavioral Neurobiology at the University of Tübingen and their team have investigated how the brain areas share the tasks of consolidating newly learned things and what role sleep plays in this.

Using imaging, the research team demonstrated that repetitive training allows new memory trails to be established in the cerebral cortex within a short time frame. However, these are only sufficient on their own if the learning follows a sleep phase – otherwise the brain has to resort additionally to the hippocampus for the permanent storage of new memory contents.

The study of the Tübingen neuroscientists appears in the journal Science Advances.

In the new study, the scientists gave their subjects a learning task in which they should memorize a word list in seven repetitions. While performing this task, their brain activity was recorded in a magnetic resonance imaging (MRI) machine. Twelve hours later, the subjects repeated the same task with the already learned and a new word list. Half of the people had slept during this time, the other half had stayed awake. The repeated practice led within an hour to retrieve what was learned using the posterior parietal lobe, a region of the cerebral cortex. Accordingly, the involvement of the hippocampus decreased.

Rapid formation of memory traces

“This pattern indicates a rapid formation of memory traces in the cerebral cortex,” says Monika Schönauer. “In addition, the parietal lobe shows even after twelve hours a greater activity in learned words compared to new words, which speaks for the long-term stability of these tracks.” However, the hippocampus remained uninvolved only if the subjects slept for several hours after the first session. If they stayed awake, they were needed again for familiar words, as well as for new words.

“In this way we show that memory processes proceed in the sleep that go beyond pure repetition. Learning repeats can create long-term memory traces. Whether the contents can be stored permanently independently of the hippocampus, however, depends crucially on a sleeping phase.”

Sleep, therefore, had an effect on the hippocampus in the experiment. “How the hippocampus and cerebral cortex work together is still unclear,” says Steffen Gais, head of the working group. “Understanding this interaction is an important step in the evolution of common memory theories.” Understanding the conditions under which memory is stored directly in the cerebral cortex and the role of the hippocampus is also a fundamental understanding of learning and memory disorders significant.

Source:

University of Tübingen

Media Contacts:

Lea Himmer – University of Tübingen

Image Source:

The image is in the public domain.

Original Research: Open access.

“Rehearsal initiates systems memory consolidation, sleep makes it last.”

L. Himmer, M. Schonauer, DPJ Heib, M. Schabus, S. Gais (2019). Science Advances. doi:10.1126/sciadv.aav1695

Abstract

Rehearsal initiates systems memory consolidation, sleep makes it last.

After encoding, memories undergo a transitional process termed systems memory consolidation. It allows fast acquisition of new information by the hippocampus, as well as stable storage in neocortical long-term networks, where memory is protected from interference. Whereas this process is generally thought to occur slowly over time and sleep, we recently found a rapid memory systems transition from hippocampus to posterior parietal cortex (PPC) that occurs over repeated rehearsal within one study session. Here, we use fMRI to demonstrate that this transition is stabilized over sleep, whereas wakefulness leads to a reset to naïve responses, such as observed during early encoding. The role of sleep therefore seems to go beyond providing additional rehearsal through memory trace reactivation, as previously thought. We conclude that repeated study induces systems consolidation, while sleep ensures that these transformations become stable and long lasting. Thus, sleep and repeated rehearsal jointly contribute to long-term memory consolidation.