Summary: In men with a history of childhood trauma, oxytocin reduced the activity within the amygdala and cravings for cocaine. Women who were addicted to cocaine and had experienced childhood trauma showed an increase in amygdala activity following exposure to oxytocin.

Source: Medicial University of South Carolina

A team of addiction researchers at the Medical University of South Carolina (MUSC) report in Psychopharmacology that oxytocin, a hormone produced naturally in the hypothalamus, has significant gender differences when used as a treatment for cocaine-addicted individuals with a history of childhood trauma.

The MUSC team was led by Jane E. Joseph, Ph.D., a professor in the Department of Neuroscience, and Kathleen T. Brady, M.D., Ph.D., a professor in the Department of Psychiatry and Behavioral Sciences and MUSC vice president for research.

Oxytocin has been shown to have therapeutic action in addiction, reducing cravings that could result in a relapse while also reducing brain activity associated with stress. Despite previous studies showing some potential therapeutic actions of oxytocin, it was not yet known how oxytocin influenced cravings induced by the sight of cocaine paraphernalia or whether gender-based differences existed.

To understand the role of oxytocin in addiction, it is important to understand the changes that can occur in the brain in response to environmental factors. Extremely traumatic events such as childhood trauma can lead to post-traumatic stress disorder, which can change neural connections within the brain. Addiction can lead to changes in the connections of the brain as well, and the areas changed by both trauma and addiction can overlap.

The amygdala, one region in the brain that experiences these changes, is rich in oxytocin receptors and can become hyperreactive in response to stress. While oxytocin has been shown to reduce amygdala activity in response to stress cues, less was known about how oxytocin might affect cravings for cocaine in addicted individuals.

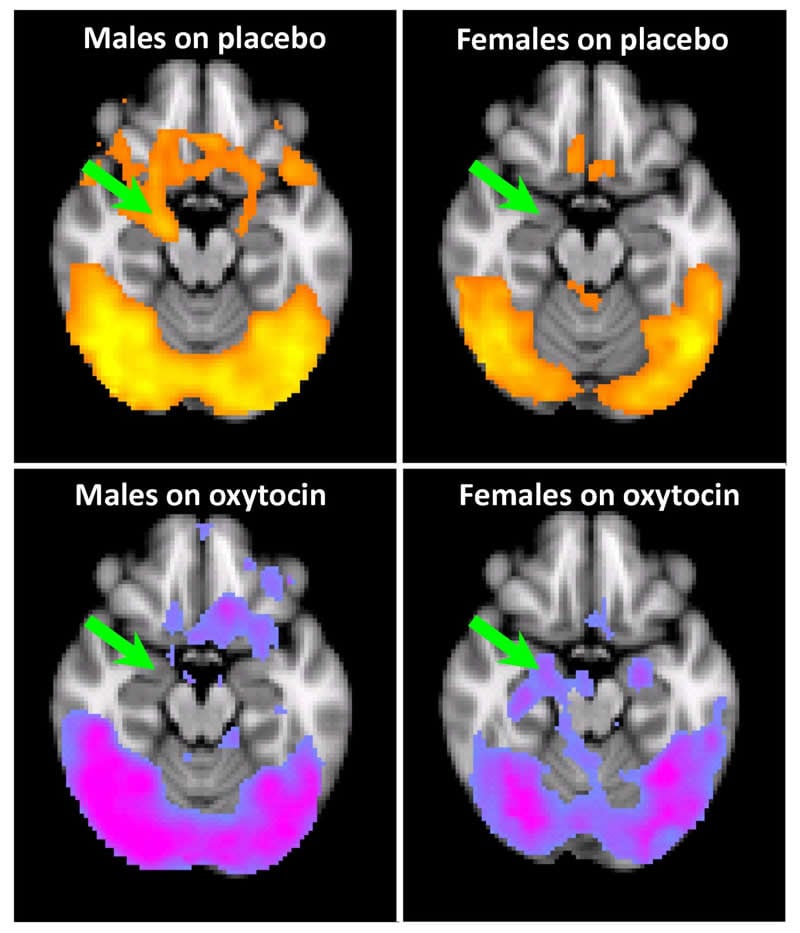

To test the craving response, the researchers asked 67 study participants, while in an MRI, to view images of drug paraphernalia alongside images of more mundane items. Viewing images of drug paraphernalia led to the amygdala “lighting up” in drug-addicted men, correlating to an increase in cravings for cocaine. Participants were then each treated with either oxytocin or a placebo, and the effect on the amygdala was measured.

In men with a history of trauma, the response was as predicted. Oxytocin reduced the activity within the amygdala, as well as the cravings that the individuals felt for cocaine, consistent with previous studies demonstrating the hormone’s therapeutic effect.

Surprisingly, this did not hold true for women with a history of trauma. While the amygdala of men with cocaine addiction would become highly active in response to visual drug cues, that of women with cocaine addiction and a history of trauma showed little activity.

“When the women with trauma were viewing the cocaine cues on placebo, they didn’t have a strong response to begin with, which was surprising,” said Joseph. “In fact, the treatment with oxytocin led to the response in the brain to drug paraphernalia being enhanced and exacerbated.”

Historically, cocaine-addicted women have worse treatment outcomes than their male counterparts. This study clearly points to the need to flesh out the trauma-induced changes in the brain, explore how they differ by gender and better understand how they affect addiction. It also suggests that treating women with a history of childhood trauma with oxytocin alone might increase both amygdala activity and cravings, potentially leading to a higher incidence of relapse.

“Even though more men use cocaine, it really has more devastating effects on women when they relapse, and they’re much more sensitive to cocaine,” said Joseph.

Joseph sees several plausible explanations for the study’s surprising findings that gender matters when it comes to the response of cocaine-addicted individuals, with a history of trauma, to oxytocin treatment. Men may be more susceptible to the visual cues of drug paraphernalia and the cravings that they induce. In contrast, women may be more susceptible to “stress-associated” cues, such as visuals that relate to past traumas, which could increase amygdala response. Alternatively, women might have a blunted response in the amygdala to stress and cravings as a result of changes that could occur in response to the initial trauma-induced hyperreactivity. However, as this study only looked at drug cues and craving responses, these hypotheses must be evaluated in future studies.

Existing therapies for addiction may not have been developed with attention to how gender affects treatment responses, perhaps accounting in part for the increased rates of treatment failures in women. Better understanding of the intricacies of trauma, addiction and gender differences could move addiction researchers one step closer to finding effective and personalized therapies for everyone.

“The search for a medication to treat cocaine use disorder has been unsuccessful to date,” said Brady. “Exploring subgroups of individuals, such as those with childhood trauma, and agents with novel mechanisms of action, like oxytocin, is critical to moving the field forward.”

The study was completed with support from the National Institute on Drug Abuse and the South Carolina Clinical & Translational Research (SCTR) Institute, a Clinical and Translational Science Awards hub headquartered at MUSC. SCTR provided data management and the collection and processing of patient samples through the Nexus Research Center.

Source:

Medicial University of South Carolina

Media Contacts:

Heather Woolwine – Medicial University of South Carolina

Image Source:

The image is credited to Joseph et al / Psychopharmacology.

Original Research: Closed access

“Neural correlates of oxytocin and cue reactivity in cocaine-dependent men and women with and without childhood trauma”. Jane E. Joseph, Aimee McRae-Clark, Brian J. Sherman, Nathaniel L. Baker, Megan Moran-Santa Maria & Kathleen T. Brady .

Psychopharmacology doi:10.1007/s00213-009-1721-2.

Abstract

Neural correlates of oxytocin and cue reactivity in cocaine-dependent men and women with and without childhood trauma

Rationale

Women with cocaine use disorder have worse treatment outcomes compared with men. Sex differences in cocaine addiction may be driven by differences in neurobiology or stress reactivity. Oxytocin is a potential therapeutic for stress reduction in substance use disorders, but no studies have examined the effect of oxytocin on neural response to drug cues in individuals with cocaine use disorders or potential sex differences in this response.

Objectives

The goal of this study was to examine the effect of intranasal oxytocin on cocaine cue reactivity in cocaine dependence, modulated by gender and history of childhood trauma.

Methods

Cocaine-dependent men with (n = 24) or without (n = 19) a history of childhood trauma and cocaine-dependent women with (n = 16) or without (n = 8) a history of childhood trauma completed an fMRI cocaine cue reactivity task under intranasal placebo or oxytocin (40 IU) on two different days. fMRI response was measured in the right amygdala and dorsomedial prefrontal cortex (DMPFC).

Results

In the DMPFC, oxytocin reduced fMRI response to cocaine cues across all subject groups. However, in the amygdala, only men with a history of childhood trauma showed a significantly reduced fMRI response to cocaine cues on oxytocin versus placebo, while women with a history of childhood trauma showed an enhanced amygdala response to cocaine cues following oxytocin administration. Cocaine-dependent subjects with no history of childhood trauma showed no effect of oxytocin on amygdala response.

Conclusions

Oxytocin can reduce cue reactivity in cocaine dependence, but its effect is modified by sex and childhood trauma history. Whereas men with cocaine dependence may benefit from oxytocin administration, additional studies are needed to determine whether oxytocin can be an effective therapeutic for cocaine-dependent women.