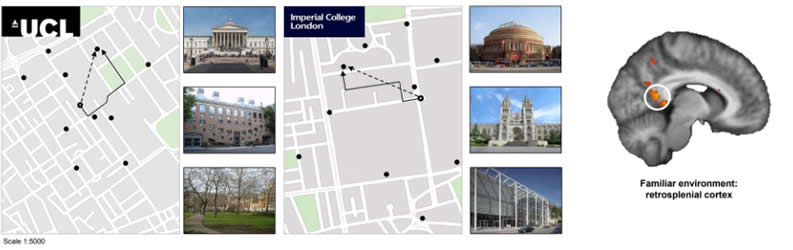

Summary: The posterior hippocampus tracks distance to a newly learned location, as well as familiar environments. By contrast, when navigating a familiar location, the retrosplenial cortex takes over responsibility for tracking distance. The findings shed light on how the brain navigates and encodes spatial information.

Source: UCL

UCL scientists have discovered the key brain region for navigating well-known places, helping explain why brain damage seen in early stages of Alzheimer’s disease can cause such severe disorientation.

The study, published today in Cerebral Cortex, is the first to identify the specific brain regions used in guiding the navigation of familiar places.

Researchers observed that a brain region long-known to be involved in new learning – the hippocampus – was involved in tracking distance to a destination in a ‘newly learned’ environment.

However, when navigating a familiar place, another brain region – the retrosplenial cortex – was found to “take over” tracking the distance to the destination.

“Our findings are significant because they reveal that there are in fact two different parts of the brain that guide navigation,” says Professor Hugo Spiers (UCL Experimental Psychology), senior author on the study.

“Which part gets used depends on whether you are in a place you know well or a place you only visited recently. The results help to explain why damage to the retrosplenial cortex in Alzheimer’s disease is so debilitating, and why these patients get lost even in very familiar environments.”

The research team worked with students from UCL and Imperial College London. The students’ brain activity was monitored as they navigated a simulation of their own familiar campus and the other university’s campus, which was ‘newly learned’ days before.

The researchers also explored the impact of Sat-Navs by having students navigate the campuses with directions overlaid on the route in front of them. Strikingly, neither the hippocampus nor retrosplenial cortex continued to track distance to the destination when using this Sat-Nav-like device.

“We wondered whether navigating a very familiar place would be similar to using a Sat-Nav, seeing as you don’t need to think as much about where you’re going in a familiar place,” says Professor Spiers. “However, the results show this isn’t the case; the brain is more engaged in processing the space when you are using your memory.”

“This has significant implications for ongoing research into Alzheimer’s disease,” says Dr. Zita Patai (UCL Experimental Psychology), first author on the study. “Specifically, how the deterioration of different brain regions contributes to fundamental behaviors such as memory and navigation, and how this changes over time.”

Funding: The research was funded by the Wellcome Trust, James S. McDonnell Foundation, and the Canadian Institute of Health Research.

Source:

UCL

Media Contacts:

Tash Payne – UCL

Image Source:

The image is credited to UCL.

Original Research: Open access

E Zita Patai, Amir-Homayoun Javadi, Jason D Ozubko, Andrew O’Callaghan, Shuman Ji, Jessica Robin, Cheryl Grady, Gordon Winocur, R Shayna Rosenbaum, Morris Moscovitch, Hugo J Spiers, “Hippocampal and Retrosplenial Goal Distance Coding After Long-term Consolidation of a Real-World Environment”, Cerebral Cortex, bhz044, doi:10.1093/cercor/bhz044

Abstract

Hippocampal and Retrosplenial Goal Distance Coding After Long-term Consolidation of a Real-World Environment

Recent research indicates the hippocampus may code the distance to the goal during navigation of newly learned environments. It is unclear however, whether this also pertains to highly familiar environments where extensive systems-level consolidation is thought to have transformed mnemonic representations. Here we recorded fMRI while University College London and Imperial College London students navigated virtual simulations of their own familiar campus (>2 years of exposure) and the other campus learned days before scanning. Posterior hippocampal activity tracked the distance to the goal in the newly learned campus, as well as in familiar environments when the future route contained many turns. By contrast retrosplenial cortex only tracked the distance to the goal in the familiar campus. All of these responses were abolished when participants were guided to their goal by external cues. These results open new avenues of research on navigation and consolidation of spatial information and underscore the notion that the hippocampus continues to play a role in navigation when detailed processing of the environment is needed for navigation.