Summary: Researchers say most people are not aware that two forms of the letter ‘g’ exist and, for those who are aware, most can not correctly identify or write the typeset version we usually see. The findings suggest the important role writing styles play in letter learning.

Source: Johns Hopkins University.

Despite seeing it millions of times in pretty much every picture book, every novel, every newspaper, and every email message, people are essentially unaware of the more common version of the lowercase print letter “g,” Johns Hopkins researchers have found.

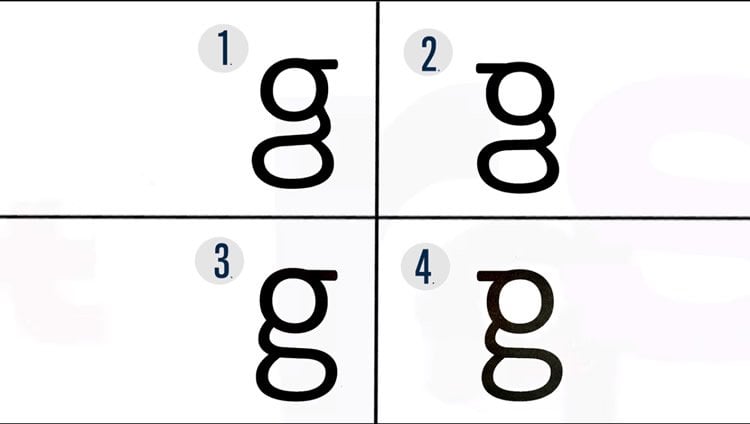

Most people don’t even know that two forms of the letter—one usually handwritten, the other typeset—exist. And if they do, they can’t write the typeset one we typically see. They can’t even pick the correct version of it out of a lineup.

The findings, which suggest the important role writing plays in learning letters, appear in the Journal of Experimental Psychology: Human Perception & Performance.

“We think that if we look at something enough, especially if we have to pay attention to its shape as we do during reading, then we would know what it looks like. But our results suggest that’s not always the case,” said Johns Hopkins cognitive scientist Michael McCloskey, the study’s senior author. “What we think may be happening here is that we learn the shapes of most letters in part because we have to write them in school. ‘Looptail g’ is something we’re never taught to write, so we may not learn its shape as well.”

Unlike most letters, “g” has two lowercase print versions. There’s the opentail one that most everyone uses when writing by hand; it looks like a loop with a fishhook hanging from it. Then there’s the looptail g, which is by far the more common, seen in everyday fonts like Times New Roman and Calibri and, hence, in most printed and typed material.

To test people’s awareness of the g they tend to write and the g they tend to read, the researchers conducted a three-part experiment:

First, they wanted to figure out if people knew there were two lowercase print gs. They asked 38 adults to list letters with two lowercase print varieties. Just two named g. And only one could write both forms correctly.

“We would say: ‘There’re two forms of g. Can you write them?’ And people would look at us and just stare for a moment, because they had no idea,” said first author Kimberly Wong, a junior undergraduate at Johns Hopkins. “Once you really nudged them on, insisting there are two types of g, some would still insist there is no second g.”

Next, the researchers asked 16 new participants to silently read a paragraph filled with looptail gs, but to say each word with a “g” aloud. Immediately after participants finished, having paid particular attention to each of 14 gs, they were asked to write the “g” that they just saw 14 times. Half of them wrote the wrong type, the opentail. The others attempted to write a looptail version, but only one could.

Finally, the team asked 25 participants to identify the correct looptail g in a multiple-choice test with four options. Just seven succeeded.

“They don’t entirely know what this letter looks like, even though they can read it,” said co-author Gali Ellenblum, a graduate student in cognitive science. “This is not true of letters in general. What’s going on here?”

This outlier g seems to demonstrate that our knowledge of letters can suffer when we don’t write them. And as we write less and become more dependent on electronic devices, the researchers wonder about the implications for reading.

“What about children who are just learning to read? Do they have a little bit more trouble with this form of g because they haven’t been forced to pay attention to it and write it?” McCloskey said. “That’s something we don’t really know. Our findings give us an intriguing way of looking at questions about the importance of writing for reading. Here is a naturally occurring situation where, unlike most letters, this is a letter we don’t write. We could ask whether children have some reading disadvantage with this form of g.”

Co-authors include Frempongma Wadee, who graduated from Johns Hopkins with her bachelor’s degree last year.

Source: Jill Rosen – Johns Hopkins University

Publisher: Organized by NeuroscienceNews.com.

Image Source: NeuroscienceNews.com image is adapted from the Johns Hopkins University video.

Video Source: The videos are credited to Johns Hopkins University.

Original Research: Abstract for “The Devil’s in the g-tails: Deficient letter-shape knowledge and awareness despite massive visual experience” by Wong, Kimberly; Wadee, Frempongma; Ellenblum, Gali; and McCloskey, Michael in Journal of Experimental Psychology: Human Perception & Performance. Published April 3 2018.

doi:10.1037/xhp0000532

[cbtabs][cbtab title=”MLA”]Johns Hopkins University “A Letter of the Alphabet We Can Read But Not Write?.” NeuroscienceNews. NeuroscienceNews, 4 April 2018.

<https://neurosciencenews.com/letter-g-learning-8724/>.[/cbtab][cbtab title=”APA”]Johns Hopkins University (2018, April 4). A Letter of the Alphabet We Can Read But Not Write?. NeuroscienceNews. Retrieved April 4, 2018 from https://neurosciencenews.com/letter-g-learning-8724/[/cbtab][cbtab title=”Chicago”]Johns Hopkins University “A Letter of the Alphabet We Can Read But Not Write?.” https://neurosciencenews.com/letter-g-learning-8724/ (accessed April 4, 2018).[/cbtab][/cbtabs]

Abstract

The Devil’s in the g-tails: Deficient letter-shape knowledge and awareness despite massive visual experience

Knowledge of letter shapes is central to reading. In experiments focusing primarily on a single letter shape—the “looptail” lowercase print G—we found surprising gaps in skilled readers’ knowledge. In Experiment 1 most participants failed to recall the existence of looptail g when asked if G has two lowercase print forms, and almost none were able to write looptail g accurately. In Experiment 2 participants searched for Gs in text with multiple looptail gs. Asked immediately thereafter to write the g form they had seen, half the participants produced an “opentail” g (the typical handwritten form), and only one wrote looptail g accurately. In Experiment 3 participants performed poorly in discriminating looptail g from distractors with important features mislocated or misoriented. These results have implications for understanding types of knowledge about letters, and how this knowledge is acquired. For example, our findings speak to hypotheses concerning the role of writing in learning letter shapes. More generally, our findings raise questions about the conditions under which massive exposure does, and does not, yield detailed, accurate, accessible knowledge. In this context we relate our findings to studies showing poor knowledge or memory for various types of stimuli despite extensive exposure.