In an article appearing online today in the journal Science, a group of researchers, including University of Rochester neurologist Steve Goldman, M.D., Ph.D., review the potential and challenges facing the scientific community as therapies involving stem cells move closer to reality.

The review article focuses on pluripotent stem cells (PSCs), which are stem cells that can give rise to all cell types. These include both embryonic stem cells, and those derived from mature cells that have been “reprogrammed” or “induced” – a process typically involving a patient’s own skin cells – so that they possess the characteristics of stem cells found at the earliest stage of development. These cells can then be differentiated, through careful manipulation of chemical and genetic signaling, to become virtually any cell type found in the body.

While the process of making induced PSCs is relatively new in scientific terms – it was first demonstrated that skin cells could be successfully reprogrammed in 2007 – one of the reasons that these cells are viewed with promise by the scientific community is because they are derived from the patient’s own tissue. Consequently, cells used for transplant can be a genetic match and far less likely to be rejected, thereby potentially mitigating the need to use immune system suppressing drugs.

The article addresses the current state of efforts to apply PSCs to treat a number of diseases, including diabetes, liver disease, and heart disease. Goldman, a distinguished professor and co-director of the University of Rochester School of Medicine and Dentistry Center for Translational Neuromedicine, reviewed the current state of therapies for neurological diseases.

While progress has been made over the last several years, the authors point out that significant challenges remain. Scientists must be able to obtain the precise cell populations required to treat the target disease, and once transplanted, make sure that these cells get to where they are needed and integrate into existing tissue. The cells that are transplanted must also first be checked for purity and screened for unwanted cells that could give rise to tumors.

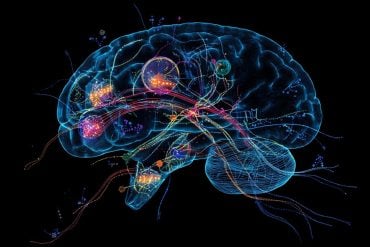

Goldman and his co-authors contend that “the brain is arguable the most difficult of the organs in which to employ stem cell-based therapeutics.” The complex connections and interdependency between neurons and the myriad of other support cells found in central nervous mean that a precise reconstruction of damaged areas of the brain is often impractical. Also, many degenerative neurological disorders, including Alzheimer’s, involve more than one cell type, making them difficult targets for stem cell therapies, at least in the near future.

Instead, Goldman argues that neurological diseases that involve a single cell type – at least at the early stages – are more promising targets for PSC-based therapies. These include Parkinson’s disease and Huntington’s disease, which are characterized by the loss of dopamine-producing neurons and medium spiny neurons, respectively. In particular, diseases that involved support cells found in the brain known as glia – such as multiple sclerosis, white matter stroke, cerebral palsy, and pediatric leukodystrophies – are especially strong candidates for stem cell therapies. These diseases are characterized by the loss of a specific glial cell type called the oligodendrocyte, which makes myelin, the insulation that allows electrical signals to travel between nerve cells. In multiple sclerosis, the body’s own immune system attacks and destroys these cells and, over time, communication between cells is disrupted or even lost.

Oligodendrocytes are the offspring of another cell called the oligodendrocyte progenitor cell, or OPC. Scientists have long speculated that, if successfully transplanted into the diseased or injured brain, OPCs might be able to produce new oligodendrocytes capable of restoring lost myelin, thereby reversing the damage caused by these diseases.

Goldman’s group has already shown that OPCs produced from PSCs obtained from human skin cells successfully restore myelin in the brains and spinal cords of myelin-deficient mice, and can rescue and restore function to mice that would have otherwise died. While this work demonstrated the promise of stem cell therapies, it also illustrated the challenges facing scientists. It took Goldman’s lab four years to establish the exact chemical signaling required to reprogram, produce, and ultimately purify OPCs in sufficient quantities for transplantation, and only recently has the group developed methods for producing the cells in purity and quantity sufficient to transplant into humans.

The authors contend that future progress will depend upon continued close collaboration between scientists and clinicians, and between academia, industry and regulatory bodies to overcome the remaining barriers to bringing new stem cell-based therapies to patients with these devastating diseases.

Additional authors include Ira Fox, Johnny Huard, and Massimo Trucco with the University of Pittsburgh, George Daley with Harvard University, and Timothy Kamp with the University of Wisconsin.

Contact: Mark Michaud – University of Rochester Medical Center

Source: University of Rochester Medical Center press release

Image Source: The image is adapted from the University of Rochester Medical Center press release

Original Research: Abstract for “Use of differentiated pluripotent stem cells as replacement therapy for treating disease” by Ira J. Fox, George Q. Daley, Steven A. Goldman, Johnny Huard, Timothy J. Kamp, and Massimo Trucco in Science. Published online August 22 2014 doi:10.1126/science.1247391