Summary: A new study identifies neurons in the hippocampus that store food-specific memories, directly influencing overeating and body weight. These neurons, which encode memories for sugar and fat, act as “memory traces” that drive dietary behavior and metabolism. Silencing these neurons in mice disrupted sugar-related memories, reduced intake, and prevented weight gain, even on high-sugar diets.

The findings highlight how memory systems evolved for survival now contribute to overeating in modern food-rich environments. The study reveals specific brain circuits for sugar and fat memories, opening doors for targeted obesity treatments. This research underscores the critical role of memory in shaping dietary behavior and metabolic health.

Key Facts:

- Memory and Overeating: Food-specific memories stored in hippocampal neurons influence eating behavior and body weight.

- Neural Specialization: Separate neurons encode sugar and fat memories, with distinct effects on intake.

- Therapeutic Potential: Targeting these circuits could disrupt overeating and improve metabolic health.

Source: Monell Chemical Senses Center

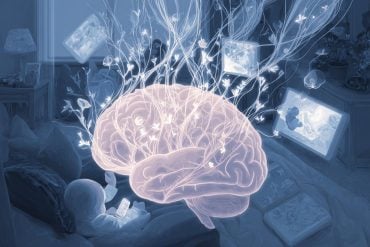

Can memory influence what and how much we eat? A groundbreaking Monell Chemical Senses Center study, which links food memory to overeating, answered that question with a resounding “Yes.”

Led by Monell Associate Member Guillaume de Lartigue, PhD, the research team identified, for the first time, the brain’s food-specific memory system and its direct role in overeating and diet-induced obesity.

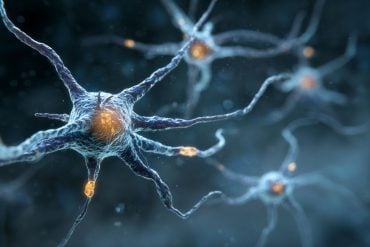

Published in Nature Metabolism, they describe a specific population of neurons in the mouse brain that encode memories for sugar and fat, profoundly impacting food intake and body weight.

“In today’s world, we are constantly bombarded with advertisements and environmental triggers designed to remind us of pleasurable food experiences,” said Dr. de Lartigue.

“What’s surprising is that we’ve pinpointed a specific population of neurons in the hippocampus that not only forms these food-related memories but also drives our eating behavior. This connection could have significant implications for body weight and metabolic health.”

These neurons encode memories of the spatial location of nutrient-rich foods, acting as a “memory trace,” particularly for sugar and fat.

Silencing these neurons impairs an animal’s ability to recall sugar-related memories, reduces sugar consumption, and prevents weight gain, even when animals are exposed to diets that contribute to excessive weight gain.

Conversely, reactivating these neurons enhances memory for food, increasing consumption and demonstrating how food memories influence dietary behavior.

These findings introduce two new concepts: first, evidence that specific neurons in the brain store food-related memories, and second, that these memories directly impact food intake.

“While it’s no surprise that we remember pleasurable food experiences, it was long assumed that these memories had little to no impact on eating behavior,” said Dr. de Lartigue.

“What’s most surprising is that inhibition of these neurons prevents weight gain, even in response to diets rich in fat and sugar.”

Memory’s Underappreciated Role

Memory is often overlooked as a key driver of food intake, but this study demonstrates a direct link between memory and metabolism. What sets this discovery apart from other studies related to memory is its implications for understanding metabolic health.

Deleting sugar-responsive neurons in the hippocampus of the animals not only disrupts memory but also reduces sugar intake and protects against weight gain, even when animals are exposed to high-sugar diets.

This highlights a direct link between certain brain circuits involved in memory and metabolic health, which has been largely overlooked in the field of obesity research.

“Memory systems in the hippocampus evolved to help animals locate and remember food sources critical for survival,” said first author Mingxin Yang, a University of Pennsylvania doctoral student in the de Lartigue lab.

“In modern environments, where food is abundant and cues are everywhere, these memory circuits may drive overeating, contributing to obesity.”

Specific, Yet Independent Circuits

Another key discovery is that food-related memories are highly specific. Sugar-responsive neurons encode and influence only sugar-related memories and intake, while fat-responsive neurons impact only fat intake. These neurons do not affect other types of memory, such as spatial memory for non-food-related tasks.

“The specificity of these circuits is fascinating,” said de Lartigue.

“It underscores how finely tuned the brain is for linking food to behavior, ensuring animals can differentiate between various nutrient sources in their environment.”

We have separate types of neurons that encode memory for foods rich in fat versus memory for foods rich in sugar. These separate systems presumably evolved because foods in nature rarely contain both fat and sugar, surmise the authors.

Implications for Treating Obesity

The study’s findings open new possibilities for addressing overeating and obesity. By targeting hippocampal memory circuits, it may be possible to disrupt the memory triggers that drive consumption of unhealthy, calorie-dense foods.

“These neurons are critical for linking sensory cues to food intake,” said Dr. de Lartigue. “Their ability to influence both memory and metabolism makes them promising targets for treating obesity in today’s food-rich world.”

Funding: This collaborative study was conducted with colleagues from the University of Pennsylvania and the University of Southern California and was supported by the National Institutes of Health and the American Heart Association.

About this memory and obesity research news

Author: Karen Kreeger

Source: Monell Chemical Senses Center

Contact: Karen Kreeger – Monell Chemical Senses Center

Image: The image is credited to Neuroscience News

Original Research: Open access.

“Separate orexigenic hippocampal ensembles shape dietary choice by enhancing contextual memory and motivation” by Guillaume de Lartigue et al. Nature Metabolism

Abstract

Separate orexigenic hippocampal ensembles shape dietary choice by enhancing contextual memory and motivation

The hippocampus (HPC) has emerged as a critical player in the control of food intake, beyond its well-known role in memory.

While previous studies have primarily associated the HPC with food intake inhibition, recent research suggests a role in appetitive processes.

Here we identified spatially distinct neuronal populations within the dorsal HPC (dHPC) that respond to either fats or sugars, potent natural reinforcers that contribute to obesity development.

Using activity-dependent genetic capture of nutrient-responsive dHPC neurons, we demonstrate a causal role of both populations in promoting nutrient-specific intake through different mechanisms.

Sugar-responsive neurons encoded spatial memory for sugar location, whereas fat-responsive neurons selectively enhanced the preference and motivation for fat intake.

Importantly, stimulation of either nutrient-responsive dHPC neurons increased food intake, while ablation differentially impacted obesogenic diet consumption and prevented diet-induced weight gain.

Collectively, these findings uncover previously unknown orexigenic circuits underlying macronutrient-specific consumption and provide a foundation for developing potential obesity treatments.