Summary: People with two common types of dementia, Lewy body dementia, and Alzheimer’s disease, have unique walking patterns. The gait type signals subtle differences between the two disorders. Those with Lew body dementia change their steps more, varying the step time and length. They also display more asymmetry in movement compared to those with Alzheimer’s disease. Researchers say gait could be a clinical biomarker for dementia subtypes.

Source: Newcastle University

For the first time, scientists at Newcastle University have shown that people with Alzheimer’s disease or Lewy body dementia have unique walking patterns that signal subtle differences between the two conditions.

The research, published today in Alzheimer’s & Dementia: The Journal of the Alzheimer’s Association, shows that people with Lewy body dementia change their walking steps more – varying step time and length – and are asymmetric when they move, in comparison to those with Alzheimer’s disease.

It is a first significant step towards establishing gait as a clinical biomarker for various subtypes of the disease and could lead to improved treatment plans for patients.

Useful diagnostic tool

Dr Ríona McArdle, Post-Doctoral Researcher at Newcastle University’s Faculty of Medical Sciences, led the Alzheimer’s Society-funded research.

She said: “The way we walk can reflect changes in thinking and memory that highlight problems in our brain, such as dementia.”

“Correctly identifying what type of dementia someone has is important for clinicians and researchers as it allows patients to be given the most appropriate treatment for their needs as soon as possible.”

“The results from this study are exciting as they suggest that walking could be a useful tool to add to the diagnostic toolbox for dementia.”

“It is a key development as a more accurate diagnosis means that we know that people are getting the right treatment, care and management for the dementia they have.”

Current diagnosis of the two types of dementia is made through identifying different symptoms and, when required, a brain scan.

For the study, researchers analysed the walk of 110 people, including 29 older adults whose cognition was intact, 36 with Alzheimer’s disease and 45 with Lewy body dementia.

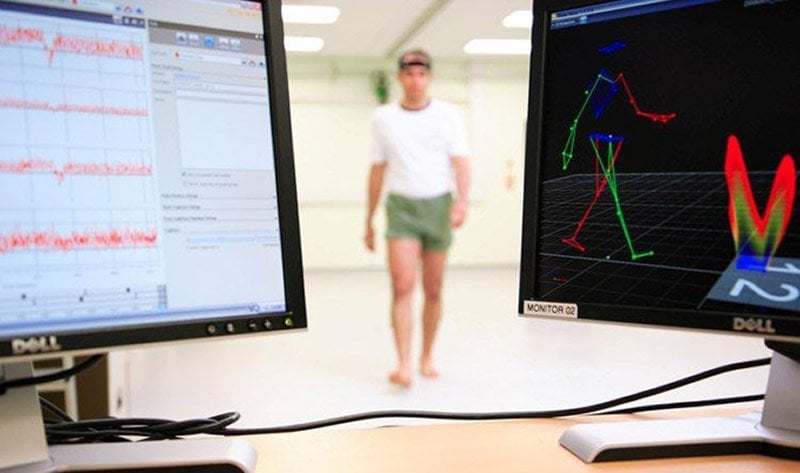

The participants took part in a simple walking test at the Gait Lab of the Clinical Ageing Research Unit, an NIHR-funded research initiative jointly run by Newcastle Hospitals NHS Foundation Trust and Newcastle University.

Participants moved along a walkway – a mat with thousands of sensors inside – which captured their footsteps as they walked across it at their normal speed and this revealed their walking patterns.

People with Lewy body dementia had a unique walking pattern in that they changed how long it took to take a step or the length of their steps more frequently than someone with Alzheimer’s disease, whose walking patterns rarely changed.

When a person has Lewy body dementia, their steps are more irregular and this is associated with increased falls risk. Their walking is more asymmetric in step time and stride length, meaning their left and right footsteps look different to each other.

Scientists found that analysing both step length variability and step time asymmetry could accurately identify 60% of all dementia subtypes – which has never been shown before.

Further work will aim to identify how these characteristics enhance current diagnostic procedures, and assess their feasibility as a screening method. It is hoped that this tool will be available on the NHS within five years.

Pioneering study

Dr James Pickett, Head of Research at Alzheimer’s Society, said: “In this well conducted study we can see for the first time that the way we walk may provide clues which could help us distinguish between Alzheimer’s disease and Lewy body dementia.

“This research – funded by the Alzheimer’s Society – is pioneering for dementia. It shows promise in helping to establish a novel approach to accurately diagnose different types of dementia.”

“We know that research will beat dementia, and provide invaluable support for the 850,000 people living with the condition in the UK today. It’s now vital that we continue to support promising research of this kind.

“We look forward to seeing larger, longer studies to validate this approach and shed light on the relationship between a person’s gait and dementia diagnosis.”

Dementia describes different brain disorders that triggers loss of brain function and these conditions are usually progressive and eventually severe.

It is estimated by the Alzheimer’s Society that people living with dementia in the UK will rise to more than one million by 2025.

Future research at Newcastle University will look at alternative methods to assess walking as part of the €50 MOBILISED-D digital monitoring project, led by Professor Lynn Rochester, which aims to develop a system of small sensors that can be worn on the body during daily routine to assess how well you walk – a sign of health and wellbeing.

Living with Lewy body dementia

Father-of-four and grandfather-of-two John Tinkler has lived with Lewy body dementia for the past three years.

The 70-year-old, of Langley Park, County Durham, was diagnosed after starting to experience difficulties walking when he began to shuffle his feet and would regularly trip over.

John, his wife, Jenny, 59, and the rest of their family, have learned to cope with the difficult diagnosis and have had to adapt their lifestyles accordingly.

Jenny, a physiotherapist, said: “Since John’s diagnosis things have been difficult and, over the years, he has deteriorated to the point where he fatigues easily, which affects his mobility, balance and coordination, and he is now struggling to get out of an armchair. In addition to this, he has joint pain and muscle cramps.

“When we were asked if John would like to take part in the Newcastle University research we didn’t hesitate to say ‘yes’ because it’s important that people do their bit to help research.”

“The findings of the study are exciting because it can help lead to a definitive diagnosis of the subtype of dementia, which will allow patients to be on the right management program as early as possible.”

“If patients and their families know the specific type of dementia they are dealing with, this enables there to be a greater understanding of the specific needs of the person living with the condition.”

“We are extremely lucky to live in an area where research into aging is among the best there is. It would be fantastic if a screening tool like this was available within the NHS for dementia patients.”

Source:

Newcastle University

Media Contacts:

Press Office – Newcastle University

Image Source:

The image is credited to Gait Lab.

Original Research: Closed access

“Do Alzheimer’s and Lewy body disease have discrete pathological signatures of gait?”. Ríona McArdle et al..

Alzheimer’s and Dementia doi:10.1016/j.jalz.2019.06.4953.

Abstract

Do Alzheimer’s and Lewy body disease have discrete pathological signatures of gait?

Objective

We aimed to refine the hypothesis that dementia has a unique signature of gait impairment reflective of underlying pathology by considering two dementia subtypes, Alzheimer’s disease (AD) and Lewy body disease (LBD), and exploring the role of cognition in disease-specific gait impairments.

Background

Accurately differentiating AD and LBD is important for treatment and disease management. Early evidence suggests gait could be a marker of dementia due to associations between discrete gait characteristics and cognitive domains.

Updated Hypothesis

We hypothesize that AD and LBD have unique signatures of gait, reflecting disease-specific cognitive profiles and underlying pathologies. An exploratory study included individuals with mild cognitive impairment or dementia due to LBD (n = 45) and AD (n = 36) and 29 older adult controls. An instrumented walkway quantified 16 gait characteristics reflecting five independent domains of locomotion (pace, rhythm, variability, asymmetry, and postural control). The LBD group demonstrated greater impairments in asymmetry and variability compared with AD; both groups were more impaired in pace and variability domains than controls. Executive dysfunction explained 11% of variance for gait variability in LBD, whereas global cognitive impairment explained 13.5% of variance in AD; therefore, gait impairments may reflect disease-specific cognitive profiles. With a refined hypothesis that AD- and LBD-specific signatures of gait reflect discrete pathologies, future studies must examine the relationship between a validated model of gait with neural networks, using recognized biomarkers and postmortem follow-up.

Major Challenges for Hypothesis

Differential diagnosis of AD and LBD used appropriate criteria and required consensus from an expert diagnostic panel to improve diagnostic accuracy. Future work should follow the framework set out in Parkinson’s disease to establish unique signatures of gait as proxy measures of disease-specific pathology; that is, use a validated gait model to explore the progressive relationship between gait, cognition, and pathology.

Linkage to Other Major Theories

These exploratory findings support the theory of interacting cognitive-motor networks, as the gait-cognition relationship may reflect cognitive control over motor networks. Unique signatures of gait may reflect different temporal patterns of pathological burden in neural areas related to cognitive and motor function.