Summary: Depending on the network state, certain neurons in the primary somatosensory cortex can be more or less excitable, which shapes stimulus processing in the brain.

Source: Max Planck Institute

Rustling leaves, light rain at the window, a quietly ticking clock – muffled sounds, just above the threshold of hearing. One moment we perceive them, the next we don’t, even if we, or the sounds, don’t seem to change. Many studies have shown that we never process an incoming stimulus, be it a sound, an image, or a touch, in the same way. This is true, even if the stimulus is exactly the same. This occurs because the impact a stimulus makes, on the brain regions that process it, depends on the momentary state of the networks those brain regions belong to. However, the factors that influence and underlie the constantly fluctuating momentary state of the networks and whether these states are random or follow a rhythm, was previously unknown.

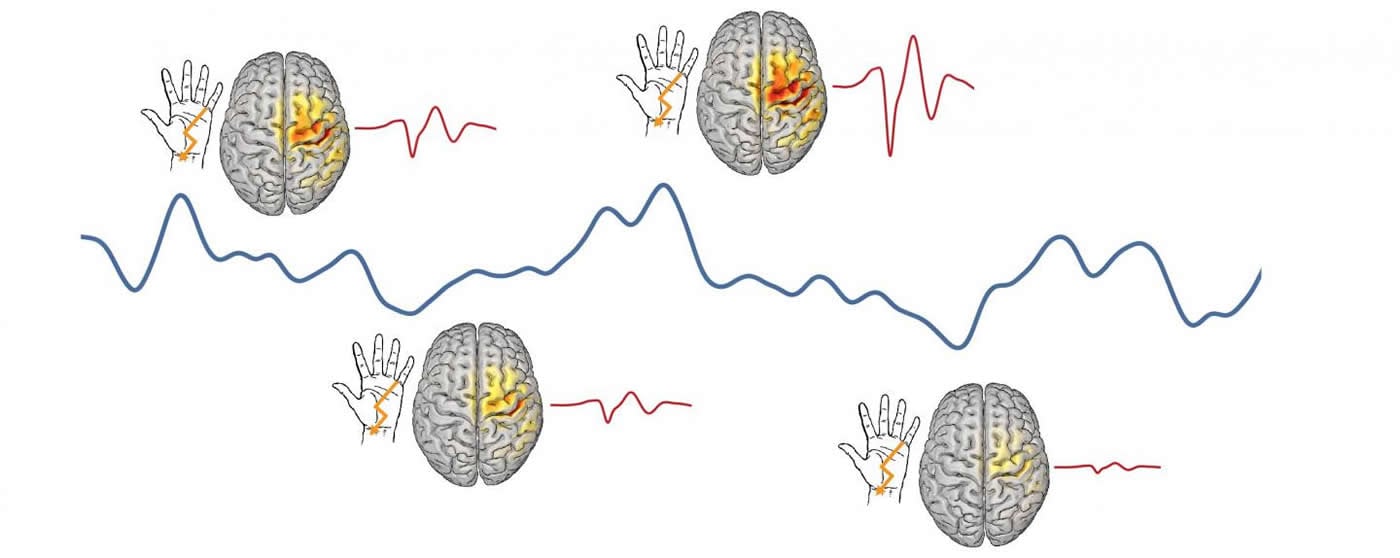

Now, scientists at the Max Planck Institute for Human Cognitive and Brain Sciences (MPI CBS) in Leipzig, Germany, have discovered that the sensitivity of the network state, at the time the stimulus-related information reaches the cerebral cortex, influences how strongly the brain reacts to the stimulus. Depending on the network state, certain nerve cells in this so-called primary somatosensory cortex can be more or less ‘excitable’, which shapes the following stimulus processing in the brain. This means that the brain’s response is modulated already at the entry to the cerebral cortex and depends on more than how the stimulus is evaluated at higher, downstream levels.

“There is always a certain amount of activity between the neurons of a network, even if there are apparently no external influences on us. So, the system is never completely still or inactive,” explains Tilman Stephani, PhD student at the MPI CBS and first author of the study, which has now been published in the Journal of Neuroscience. Rather, information is constantly arising, from inside the body about our heartbeat, digestion, or breathing, information about our position in space, the temperature, and internally generated thoughts. In addition, intrinsic neuronal activity occurs even if neuronal networks are isolated from any input. This constantly affects the excitability of various brain networks. “The dynamics from internal processes are thus associated with the system´s excitability and therefore, also the stimulus response,” says Stephani. “So, the brain does not seem to function like a computer where the same incoming information always means the same reaction.”

It turns out that fluctuations of cortical excitability do not occur completely at random but rather show a certain temporal pattern: The excitability at one moment depends on previous network states and influences subsequent ones. Scientists refer to this as long-range temporal dependency or long-lasting autocorrelation.

The fact that cortical excitability varies in this special way suggests that neuronal networks are poised at a so-called “critical” state, where there is a delicate balance between excitation and inhibition of the network. Earlier theoretical and empirical studies have indicated that such “criticality” may be a fundamental principle underlying brain functioning where information transmission and capacity are maximized. Stephani and colleagues now provide evidence that this principle may govern the variability of sensory brain responses in the human brain, too. Presumably, this serves as an adaptive mechanism of the brain to cope with the variety of information that is constantly arriving from the environment. A single stimulus should neither excite the entire system at once nor fade away too quickly.

However, it is still unknown whether greater excitability leads to a more salient experience. In other words, do the study participants perceive the intensity of the stimuli different depending on the instantaneous excitability? This is now being tested in a second study. “But other processes can also play a role here,” explains Stephani. “Attention, for example. If you direct it to something else, a first, strong brain response can still occur. However, higher brain processes downstream may then prevent it from being consciously perceived.”

The experiments were carried out by examining the response of participants’ brains to thousands of small successive electrical currents. These stimuli were applied to the participants´ forearms to stimulate the main nerve in the arm. This, in turn, produced an initial reaction 20 milliseconds later in a specific area of the brain, the somatosensory cortex. Based on the evoked EEG patterns, they were able to see how easily each individual stimulus excited the brain.

About this neuroscience research article

Source:

Max Planck Institute

Media Contacts:

Verena Müller – Max Planck Institute

Image Source:

The image is credited to Stephani/ MPI CBS.

Original Research: Closed access

“Temporal signatures of criticality in human cortical excitability as probed by early somatosensory responses”. by T. Stephani, G. Waterstraat, S. Haufe, G. Curio, A. Villringer and V. V. Nikulin. Journal of Neuroscience.

Abstract

Temporal signatures of criticality in human cortical excitability as probed by early somatosensory responses

Brain responses vary considerably from moment to moment, even to identical sensory stimuli. This has been attributed to changes in instantaneous neuronal states determining the system’s excitability. Yet the spatio-temporal organization of these dynamics remains poorly understood. Here we test whether variability in stimulus-evoked activity can be interpreted within the framework of criticality, which postulates dynamics of neural systems to be tuned towards the phase transition between stability and instability as is reflected in scale-free fluctuations in spontaneous neural activity. Using a novel non-invasive approach in 33 male human participants, we tracked instantaneous cortical excitability by inferring the magnitude of excitatory post-synaptic currents from the N20 component of the somatosensory evoked potential. Fluctuations of cortical excitability demonstrated long-range temporal dependencies decaying according to a power law across trials – a hallmark of systems at critical states. As these dynamics covaried with changes in pre-stimulus oscillatory activity in the alpha band (8–13 Hz), we establish a mechanistic link between ongoing and evoked activity through cortical excitability and argue that the co-emergence of common temporal power laws may indeed originate from neural networks poised close to a critical state. In contrast, no signatures of criticality were found in subcortical or peripheral nerve activity. Thus, criticality may represent a parsimonious organizing principle of variability in stimulus-related brain processes on a cortical level, possibly reflecting a delicate equilibrium between robustness and flexibility of neural responses to external stimuli.

Significance Statement

Variability of neural responses in primary sensory areas is puzzling, as it is detrimental to the exact mapping between stimulus features and neural activity. However, such variability can be beneficial for information processing in neural networks if it is of a specific nature, namely if dynamics are poised at a so-called critical state characterized by a scale-free spatio-temporal structure. Here, we demonstrate the existence of a link between signatures of criticality in ongoing and evoked activity through cortical excitability, which fills the long-standing gap between two major directions of research on neural variability: The impact of instantaneous brain states on stimulus processing on the one hand and the scale-free organization of spatio-temporal network dynamics of spontaneous activity on the other.