Summary: Perception of objects is robust to changes in our environment.

Source: Max Planck Institute

How is it possible for the brain to recognize drawn objects as houses or animals?

In a recent study in the Journal of Neuroscience, scientists from the Max Planck Institute for Human Cognitive and Brain Sciences in Leipzig, in collaboration with the Freie Universität Berlin and Justus Liebig University Giessen, investigated how our perception of line drawings differs from natural images.

The researchers show that the perception of objects is particularly robust to changes in our environment.

Almost everyone can represent objects with a few strokes. Kindergarten children often come home with self-drawn pictures showing mom, dad, or perhaps their own home. And even thousands of years ago, our ancestors drew animals and other objects on cave walls with strokes. But how is it actually possible that we recognize these objects as a house or an animal?

After all, line drawings are very different from the objects that surround us. They often have no color, are highly simplified, and can even have a completely different shape than the real object.

To investigate the question of how we humans perceive line drawings, scientists at MPI CBS in Leipzig, in collaboration with the Freie Universität Berlin and Justus Liebig University of Giessen, studied how our perception of line drawings differs from natural images.

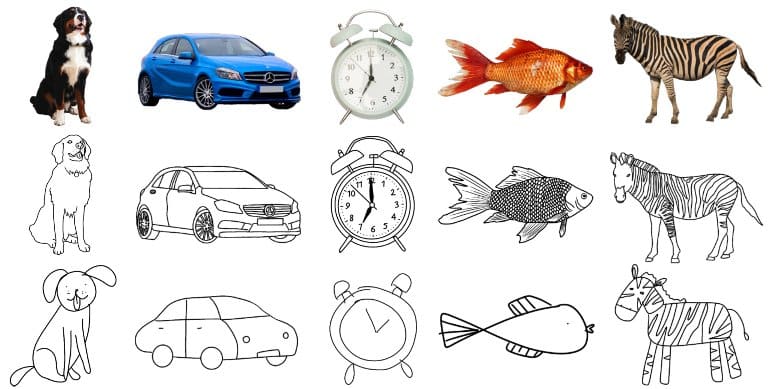

The researchers showed the study participants pictures of objects such as dogs or cars in three variants: once as a normal photo, once as a detailed line drawing of the photo, and once as a quickly scribbled sketch. While participants looked at these pictures, their brain activity was recorded with functional magnetic resonance imaging and magnetoencephalography.

Johannes Singer, lead author of the study, explains: “By using these two measurement methods, we were able to determine the brain regions involved in the perception of objects and also measure the time course of the brain activity change with millisecond precision. This way, we were able to accurately watch the brain at work as it processed images of objects as photographs and as line drawings.”

The researchers had two hypotheses here. Either our brain perceives objects differently when depicted as line drawings. Then it must resort to further processing steps. In this scenario, the line drawing of a dog has to go through an extra round in the brain, figuratively speaking, before it is recognized. Alternatively, our brains are already flexible enough to recognize a dog, even if it is only a few lines.

The results were clear: for the perception of drawings, the brain signals were very similar to those measured for photos of objects. This means that our brains can deal with line drawings of objects quite automatically.

“These results are not only interesting for our understanding of how we perceive line drawings,” says Martin Hebart, head of the study, “We also now know that our perception of objects is really particularly robust to changes in our environment.”

So, our brains make it easy for us to recognize objects when observed as line drawings. If you cannot draw very well, for example, that’s not so bad: the brain already helps us recognize what you were trying to depict. In the future, the researchers want to extend these results to a larger number of objects and to the question of whether some line drawings might be harder for our brains to perceive than others.

About this visual perception research news

Author: Press Office

Source: Max Planck Institute

Contact: Press Office – Max Planck Institute

Image: The image is credited to MPI CBS

Original Research: Closed access.

“The spatiotemporal neural dynamics of object recognition for natural images and line drawings” by Johannes J.D. Singer et al. Journal of Neuroscience

Abstract

The spatiotemporal neural dynamics of object recognition for natural images and line drawings

Drawings offer a simple and efficient way to communicate meaning. While line drawings capture only coarsely how objects look in reality, we still perceive them as resembling real-world objects.

Previous work has shown that this perceived similarity is mirrored by shared neural representations for drawings and natural images, which suggests that similar mechanisms underlie the recognition of both. However, other work has proposed that representations of drawings and natural images become similar only after substantial processing has taken place, suggesting distinct mechanisms.

To arbitrate between those alternatives, we measured brain responses resolved in space and time using fMRI and MEG, respectively, while human participants (female and male) viewed images of objects depicted as photographs, line drawings, or sketch-like drawings.

Using multivariate decoding, we demonstrate that object category information emerged similarly fast and across overlapping regions in occipital, ventral-temporal and posterior parietal cortex for all types of depiction, yet with smaller effects at higher levels of visual abstraction. In addition, cross-decoding between depiction types revealed strong generalization of object category information from early processing stages on.

Finally, by combining fMRI and MEG data using representational similarity analysis, we found that visual information traversed similar processing stages for all types of depiction, yet with an overall stronger representation for photographs.

Together our results demonstrate broad commonalities in the neural dynamics of object recognition across types of depiction, thus providing clear evidence for shared neural mechanisms underlying recognition of natural object images and abstract drawings.