Summary: New research highlights that some sedentary activities, like reading or crafting, are better for brain health than others, such as watching TV or gaming. A study of 397 older adults found that mentally stimulating and socially engaging activities support memory and thinking abilities, while passive screen time is linked to cognitive decline.

This insight is crucial, as 45% of dementia cases are linked to modifiable lifestyle factors. Researchers suggest swapping passive activities for more engaging ones to protect brain health, even during indulgent holiday marathons.

Key Facts

- Cognitive Benefits: Reading and social engagement improve brain function, unlike passive screen time.

- Preventable Risk: 45% of dementia cases could be reduced through lifestyle changes.

- Healthy Swaps: Small activity changes, like breaking up TV time with reading or movement, benefit the brain.

Source: University of South Australia

It’s that time of the year when most of us get the chance to sit back and enjoy some well-deserved down time. But whether you reach for the TV controller, or a favourite book, your choice could have implications for your long-term brain health, say researchers at the University of South Australia.

Assessing the 24-hour activity patterns of 397 older adults (aged 60+), researchers found that the context or type of activity that you engage in, matters when it comes to brain health. And specifically, that some sedentary (or sitting) behaviours are better for cognitive function than others.

Video Credit: Neuroscience News

When looking at different sedentary behaviours, they found that social or mentally stimulating activities such as reading, listening to music, praying, crafting, playing a musical instrument, or chatting with others are beneficial for memory and thinking abilities. Yet watching TV or playing video games are detrimental.

Researchers believe that there is likely a hierarchy of how sedentary behaviours relate to cognitive function, in that some have positive effects while others have negative effects.

It’s a valuable insight that could help reduce risks of cognitive impairment, particularly when at least 45% of dementia cases could be prevented through modifiable lifestyle factors.

In Australia, about 411,100 people (or one in every 1000 people) are living with dementia. Nearly two-thirds are women. Globally, the World Health Organization estimates that more than 55 million people have dementia with nearly 10 million new cases each year.

UniSA researcher Dr Maddison Mellow says that not all sedentary behaviours are equal when it comes to memory and thinking ability.

“In this research, we found that the context of an activity alters how it relates to cognitive function, with different activities providing varying levels of cognitive stimulation and social engagement,” Dr Mellow says.

“We already know that physical activity is a strong protector against dementia risk, and this should certainly be prioritised if you are trying to improve your brain health. But until now, we hadn’t directly explored whether we can benefit our brain health by swapping one sedentary behaviour for another.

“We found that sedentary behaviours which promote mental stimulation or social engagement – such as reading or talking with friends – are beneficial for cognitive function, whereas others like watching TV or gaming have a negative effect. So, the type of activity is important.

“And, while the ‘move more, sit less’ message certainly holds true for cardiometabolic and brain health, our research shows that a more nuanced approach is needed when it comes to thinking about the link between sedentary behaviours and cognitive function.”

Now, as the Christmas holidays roll around, what advice do researchers have for those who really want to indulge in a myriad of Christmas movies or a marathon of Modern Family?

“To achieve the best brain health and physical health benefits, you should prioritise movement that’s enjoyable and gets the heart rate up, as this has benefits for all aspects of health,” Dr Mellow says.

“But even small five-minute time swaps can have benefits. So, if you’re dead set on having a Christmas movie marathon, try to break up that time with some physical activity or a more cognitively engaged seated activity, like reading, at some point. That way you can slowly build up healthier habits.”

This research was conducted by a team of UniSA researchers including: Dr Maddison Mellow, Prof Dot Dumuid, Dr Alexandra Wade, Prof Tim Olds, Dr Ty Stanford, Prof Hannah Keage, and Assoc Prof Ashleigh Smith; with researchers from the University of Leicester, and the University of Newcastle.

About this brain health and neurology research news

Author: Annabel Mansfield

Source: University of South Australia

Contact: Annabel Mansfield – University of South Australia

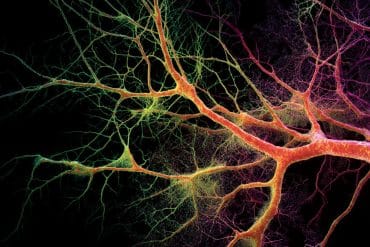

Image: The image is credited to Neuroscience News

Original Research: Open access.

“Should We Work Smarter or Harder for Our Health? A Comparison of Intensity and Domain-Based Time-Use Compositions and Their Associations With Cognitive and Cardiometabolic Health” by Maddison Mellow et al. Journals of Gerontology Series A

Abstract

Should We Work Smarter or Harder for Our Health? A Comparison of Intensity and Domain-Based Time-Use Compositions and Their Associations With Cognitive and Cardiometabolic Health

Background

Each day is made up of a composition of “time-use behaviors.” These can be classified by their intensity (eg, light or moderate–vigorous physical activity [PA]) or domain (eg, chores, socializing). Intensity-based time-use behaviors are linked with cognitive function and cardiometabolic health in older adults, but it is unknown whether these relationships differ depending on the domain (or type/context) of behavior.

Methods

This study included 397 older adults (65.5 ± 3.0 years, 69% female, 16.0 ± 3.0 years education) from Adelaide and Newcastle, Australia. Time-use behaviors were recorded using the Multimedia Activity Recall for Children and Adults, cognitive function was measured using the Addenbrooke’s Cognitive Examination III and Cambridge Neuropsychological Test Automated Battery, and systolic and diastolic blood pressure, total cholesterol, and waist–hip ratio were also recorded.

Two 24-hour time-use compositions were derived from each participant’s Multimedia Activity Recall for Children and Adults, including a 4-part intensity composition (sleep, sedentary behavior, light, and moderate–vigorous PA) and an 8-part domain composition (Sleep, Self-Care, Chores, Screen Time, Quiet Time, Household Administration, Sport/Exercise, and Social).

Results

Linear regressions found significant associations between the domain composition and both Addenbrooke’s Cognitive Examination III (p = .010) and waist–hip ratio (p = .009), and between the intensity composition and waist–hip ratio (p = .025). Isotemporal substitution modeling demonstrated that the domains of sedentary behaviors and PA impacted their associations with Addenbrooke’s Cognitive Examination III, while any PA appeared beneficial for waist–hip ratio.

Conclusions

Findings suggest the domain of behavior should be considered when aiming to support cognitive function, whereas, for cardiometabolic health, it appears sufficient to promote any type of PA.