Summary: Our brains favor learning from individuals we like over those we dislike, a phenomenon crucial for memory integration.

Through experiments involving everyday objects, the study demonstrated that our ability to connect information and form new inferences is significantly affected by our personal feelings towards the information provider. This selective memory integration can shape our perceptions and beliefs, even in neutral contexts, suggesting an innate bias in how we assimilate information.

The findings highlight the fundamental role of personal preferences in learning and the potential for reinforcing polarization in society.

Key Facts:

- Our brains preferentially learn from and integrate information presented by people we like, affecting how we connect new experiences.

- This bias in memory integration can influence our beliefs and perceptions, potentially leading to selective memory and reinforced polarization.

- The research provides a fundamental insight into how personal preferences impact learning processes, extending beyond social media filter bubbles to basic brain functions.

Source: Lund University

Our brains are “programmed” to learn more from people we like – and less from those we dislike. This has been shown by researchers in cognitive neuroscience in a series of experiments.

Memory serves a vital function, enabling us to learn from new experiences and update existing knowledge. We learn both from individual experiences and from connecting them to draw new conclusions about the world.

This way, we can make inferences about things that we don’t necessarily have direct experience of. This is called memory integration and makes learning quick and flexible.

Inês Bramão, associate professor of psychology at Lund University, provides an example of memory integration: Say you’re walking in a park. You see a man with a dog. A few hours later, you see the dog in the city with a woman. Your brain quickly makes the connection that the man and woman are a couple even though you have never seen them together.

“Making such inferences is adaptive and helpful. But of course, there’s a risk that our brain draws incorrect conclusions or remembers selectively”, says Inês Bramão.

Important who provides the information

To examine what affects our ability to learn and make inferences, Inês Bramão, along with colleagues Marius Boeltzig and Mikael Johansson, set up experiments where participants were tasked with remembering and connecting different objects. It could be a bowl, ball, spoon, scissors, or other everyday objects. It turned out that memory integration, i.e., the ability to remember and connect information across learning events, was influenced by who presented it.

If it was a person the participant liked, connecting the information was easier compared to when the information came from someone the participant disliked. The participants provided individual definitions of ‘like’ and ‘dislike’ based on aspects such as political views, major, eating habits, favorite sports, hobbies, and music.

Can be translated to politics

The findings can be applied in real life, according to the researchers. Inês Bramão takes a hypothetical example from politics:

“A political party argues for raising taxes to benefit healthcare. Later, you visit a healthcare center and notice improvements have been made. If you sympathize with the party that wanted to improve healthcare through higher taxes, you’re likely to attribute the improvements to the tax increase, even though the improvements might have had a completely different cause”.

About fundamental mechanisms

There’s already vast research describing that people learn information differently depending on the source and how that characterizes polarization and knowledge resistance.

“What our research shows is how these significant phenomena can partly be traced back to fundamental principles that govern how our memory works”, says Mikael Johansson, professor of psychology at Lund University. “

We are more inclined to form new connections and update knowledge from information presented by groups we favor. Such preferred groups typically provide information that aligns with our pre-existing beliefs and ideas, potentially reinforcing polarized viewpoints”.

Innate way of handling information

Understanding the roots of polarization, resistance to new knowledge, and related phenomena from basic brain functions offers a deeper insight into these complex behaviors, the researchers argue. So, it’s not just about filter bubbles on social media but also about an innate way of assimilating information.

“Particularly striking is that we integrate information differently depending on who is saying something, even when the information is completely neutral. In real life, where information often triggers stronger reactions, these effects could be even more prominent”, says Mikael Johansson.

About this learning and memory research news

Author: Lotte Billing

Source: Lund University

Contact: Lotte Billing – Lund University

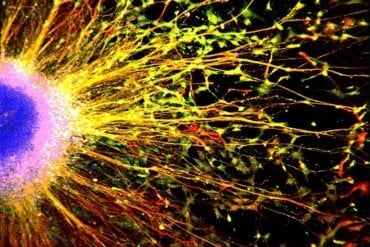

Image: The image is credited to Neuroscience News

Original Research: Open access.

“Ingroup sources enhance associative inference” by Ines Bramao et al. Communications Psychology

Abstract

Ingroup sources enhance associative inference

Episodic memory encompasses flexible processes that enable us to create and update knowledge by making novel inferences across overlapping but distinct events. Here we examined whether an ingroup source enhances the capacity to draw such inferences.

In three studies with US-American samples (NStudy1 = 53, NStudy2 = 68, NStudy3 = 68), we investigated the ability to make indirect associations, inferable from overlapping events, presented by ingroup or outgroup sources.

Participants were better at making inferences based on events presented by ingroup compared to outgroup sources (Studies 1 and 3). When the sources did not form a team, the effect was not replicated (Study 2). Furthermore, we show that this ingroup advantage may be linked to differing source monitoring resources allocated to ingroup and outgroup sources.

Altogether, our findings demonstrate that inferential processes are facilitated for ingroup information, potentially contributing to spreading biased information from ingroup sources into expanding knowledge networks, ultimately maintaining and strengthening polarized beliefs.