Summary: A new theory of gender dysphoria claims brain network activity, and not incorrect brain sex may be at the root of symptoms.

Source: SfN

A new theory of gender dysphoria argues the symptoms of the condition are due to changes in network activity, rather than incorrect brain sex, according to work recently published in eNeuro.

Gender dysphoria is a state of extreme distress caused by the feeling that a person’s true gender does not match the gender assigned at birth. The leading theory of the mechanism behind gender dysphoria attributes the condition to people possessing brains regions with the size and shape of the opposite sex, instead of their biological sex. However, recent brain imaging studies don’t support that theory.

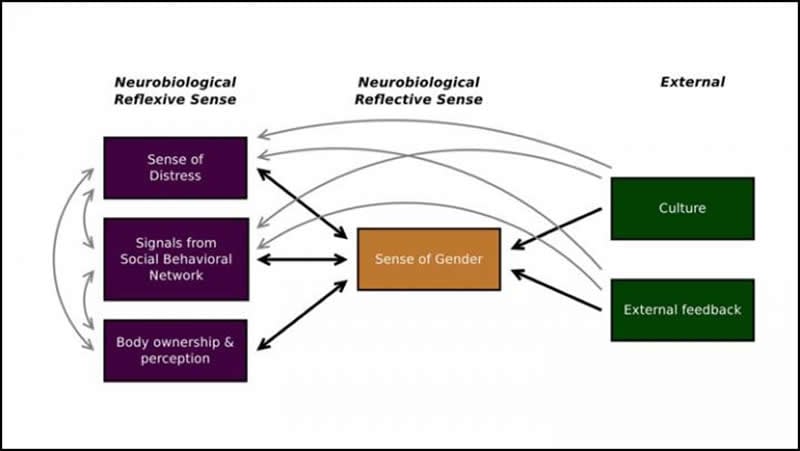

Stephen Gliske reviewed previous research and has developed a new multisense theory of gender dysphoria focused on function of brain regions, rather than only size and shape. He proposes gender dysphoria is caused by altered activity in three networks – the distress, social behavior, and body-ownership networks – affecting distress and one’s sense of their own gender. Previous studies support the premise that activity changes in these networks are associated with anatomical changes and feelings of gender dysphoria.

If supported by further research, this theory could offer ways to treat the distress of gender dysphoria patients without relying on invasive and irreversible gender reassignment surgery.

Source:

SfN

Media Contacts:

Calli McMurray – SfN

Image Source:

The image is credited to Gliske et al.

Original Research: Open access

“A new theory of gender dysphoria incorporating the distress, social behavioral, and body-ownership networks”. Stephen V. Gliske.

NeuroImage doi:10.1523/ENEURO.0183-19.2019.

Abstract

A new theory of gender dysphoria incorporating the distress, social behavioral, and body-ownership networks

When postmortem studies related to transgender individuals were first published, little was known about the function of the various identified nuclei. Now, over two decades later, significant progress has been made associating function with specific brain regions, as well as in identifying networks associated with groups of behaviors. However, much of this progress has not been integrated into the general conceptualization of gender dysphoria in humans. We hypothesize that in individuals with gender dysphoria, the aspects of chronic distress, gender atypical behavior, and incongruence between perception of gender identity and external primary sex characteristics are all directly related to functional differences in associated brain networks. We evaluated previously published neuroscience data related to these aspects and the associated functional networks, along with other relevant information. We find that the brain networks that give individuals their ownership of body parts, that influence gender typical behavior, and that are involved in chronic distress are different in individuals with and without gender dysphoria, leading to a new theory—that gender dysphoria is a sensory perception condition, an alteration in sense of gender influenced by the reflexive behavioral responses associated with each of these networks. This theory builds upon previous work that supports the relevance of the body ownership network and that questions the relevance of cerebral sexual dimorphism in regards to gender dysphoria. However, our theory uses a hierarchical executive function model to incorporate multiple reflexive factors (body ownership, gender (a)typical behavior, and chronic distress) with the cognitive, reflective process of gender identity.

Significance

Our new model highlights connections between multiple dimensions of gender dysphoria and behavioral neuroscience data, explaining the experience of gender dysphoria using relevant neural substrates and networks. This biology/symptom-based approach provides an updated theory of gender dysphoria, fostering new hypotheses to advance basic understanding of the condition. This theory may lead to therapies which directly address the underlying biology rather than just the subjective symptoms. Such therapies may also be more effective at reducing comorbid conditions (e.g., depression or suicide), given the possibility of a common, underlying biological cause.