Summary: A new study looks at Leonardo da Vinci’s contribution to neuroscience and the advancement of modern sciences.

Source: Profiles, Inc

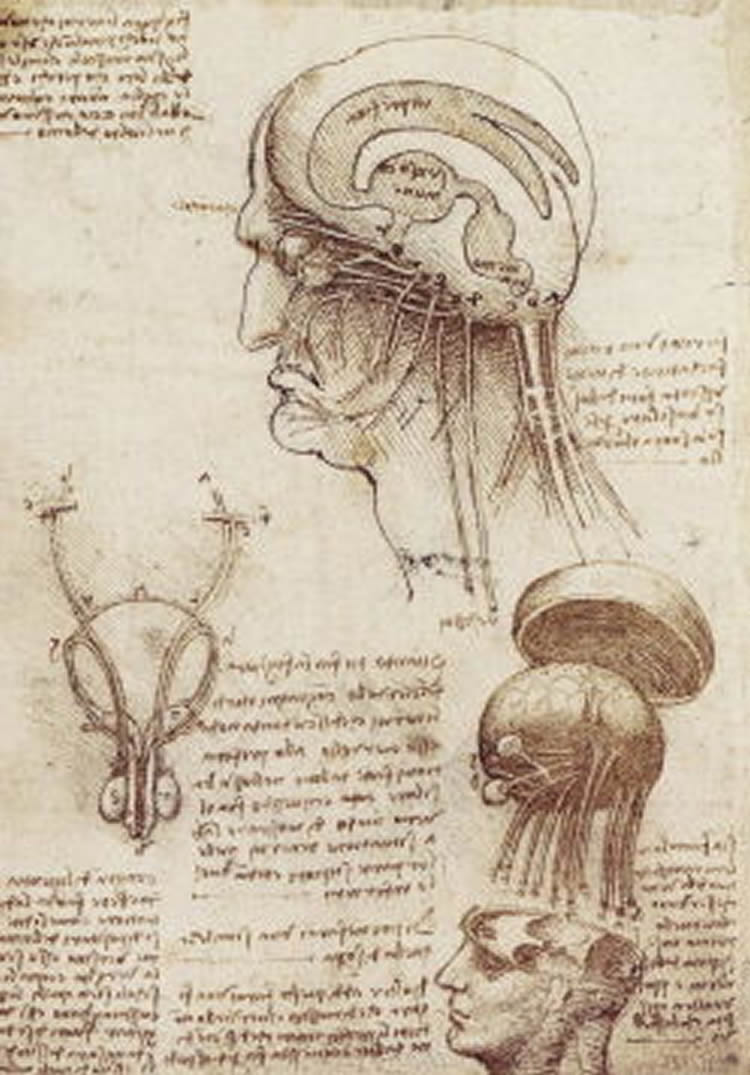

May 2, 2019, marks the 500th anniversary of Leonardo da Vinci’s death. A cultural icon, artist, engineer and experimentalist of the Renaissance period, Leonardo continues to inspire people around the globe. Jonathan Pevsner, PhD, professor and research scientist at the Kennedy Krieger Institute, wrote an article featured in the April edition of The Lancet titled, “Leonardo da Vinci’s studies of the brain.” In the piece, Pevsner highlights the exquisite drawings and curiosity, dedication and scientific rigor that led Leonardo to make penetrating insights into how the brain functions.

Through his research, Pevsner shares that Leonardo was the first to identify the olfactory nerve as a cranial nerve. He details how Leonardo performed intricate studies on the peripheral nervous system, challenging the findings of earlier authorities and introducing methods centuries earlier than other anatomists and physiologists. Pevsner also delves into Leonardo’s pioneering experiment on the ventricles by replicating his technique of injecting wax to make a cast of the ventricles in the brain to determine their overall shape and size. This further demonstrates Leonardo’s original thinking and advanced intelligence.

“Leonardo’s work reflects the emergence of the modern scientific era and forms a key part of his integrative approach to art and science,” said Pevsner.

“He asked questions about how the brain works in health and in disease. He sought to understand changes in the brain that occur in epilepsy, or why the mental state of a pregnant mother can directly affect the physical well-being of her child. At the Kennedy Krieger Institute, many of us struggle to answer the same questions. While science and technology have advanced at a breathtaking pace, we still need Leonardo’s qualities of passion, curiosity, the ability to visualize knowledge, and clear thinking to guide us forward.”

While Pevsner is viewed as an expert in Leonardo da Vinci, his main profession and passion is research into the molecular basis of childhood and adult brain disorders in his lab at Kennedy Krieger Institute. His lab reported the mutation that causes Sturge-Weber syndrome, and ongoing studies include bipolar disorder, autism spectrum disorder and schizophrenia. He is the author of the textbook, Bioinformatics and Functional Genomics.

Source:

Profiles, Inc

Media Contacts:

Jamie Watt Arnold – Profiles, Inc

Image Source:

The image is credited to Leonardo Da Vinci and is in the public domain.

Original Research: Closed access.

“Leonardo da Vinci’s studies of the brain” Jonathan Pevsner

The Lancet, Vol. 393, No. 10179, p1465–1472

Published: April 06, 2019 doi:10.1016/S0140-6736(19)30302-2

Abstract

Leonardo da Vinci’s studies of the brain

Leonardo da Vinci (1452–1519) contributed to the study of the nervous system. His earliest surviving anatomical drawings (circa 1485–93) included studies of the skull, brain, and cerebral ventricles. These works reflected his efforts to understand medieval psychology, including the localisation of sensory and motor functions to the brain. He was also the first to pith a frog, concluding that piercing the spinal medulla causes immediate death. After a 10-year interval in the early 1500s Leonardo resumed his anatomical studies and developed a method to inject hot wax into the ventricular system, creating a cast that showed the shape and extent of the ventricles. During this period he also progressed in his understanding of the anatomy of the cranial nerves. Besides being the first to identify the olfactory nerve as a cranial nerve, his dissections showed him that contrary to previous theories, the nerves do not converge on the lateral or third ventricles. Leonardo also performed detailed studies of the peripheral nervous system. Although his discoveries had little influence on the development of the field of anatomy, they represent an astonishingly sharp break from the field that had seen little if any progress in the previous 13 centuries. His work reflects the emergence of the modern scientific era and forms a key part of his integrative approach to art and science.