In mammals, embryonic cranial development is modular and step-wise: The individual cranial bones form according to a defined, coordinated schedule. The typical increase in the size of the brain in mammals in the course of evolution ultimately triggered changes in this developmental plan, as a study conducted on embryos of 134 species of animal headed by palaeontologists from the University of Zurich reveals.

Embryonic development in animals – except mice and rats – remains largely unexplored. For a research project at the University of Zurich, the embryos of 134 species of animal were studied non-invasively for the first time using microcomputer imaging, thus yielding globally unique data. The embryos studied came from museum collections all over the world. The international team of researchers headed by Marcelo Sánchez-Villagra especially studied cranial formation and discovered that the individual cranial bones develop in different phases that are characteristic for the individual species. According to the study, which was published in the journal Nature communications, how the cranial bones develop in mammals also depends on brain size.

Brain size influences the timing of cranial development

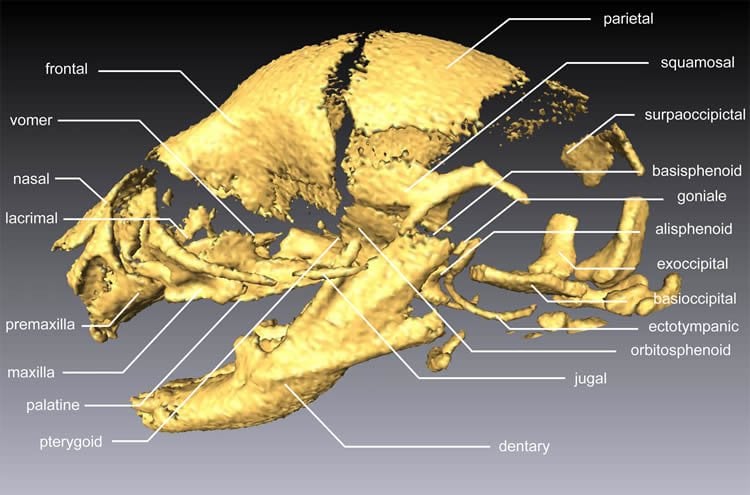

The skulls of full-grown animals consist of many individual bones that have fused together. There are two types of bone: dermal and endochondral bones. Endochondral bones form from cartilaginous tissue, which ossifies in the course of the development. Dermal bones, on the other hand, are formed in the dermis. The majority of the skull consists of dermal bones. The bones inside the skull and the petrous bone, part of the temporal bone, however, are endochondral.

As Daisuke Koyabu, now at University of Tokyo, who conducted the studies while he was a post-doc under Sánchez-Villagra, was able to demonstrate, the different bone types do not develop synchronously: Dermal cranial bones form before the endochondrals. According to Sánchez-Villagra, this indicates that the individual bones form based on a precisely defined, coordinated schedule that is characteristic for every species of animal and enables conclusions to be drawn regarding their evolutionary relationships in the tree of animal life. The researchers also discovered that individual bones in the area around the back of the head have changed their development plan in the course of evolution. “The development of larger brains in mammals triggered the changes observed in the development of bone formation,” Sánchez-Villagra.

Mammals: masticatory apparatus first

With the aid of quantitative methods and evolutionary trees, the researchers ultimately reconstructed the embryonic cranial development of the last common ancestors of all mammals, which lived 180 million years ago during the Jurassic period. As with the majority of mammals, its cranial development began with the formation of the masticatory apparatus bones.

Contact: Dr. Marcelo R. Sánchez-Villagra – University of Zurich

Source: University of Zurich press release

Image Source: The images are adapted from the University of Zurich press release.

Original Research: Full open access research for “Mammalian skull heterochrony reveals modular evolution and a link between cranial development and brain size” by Daisuke Koyabu, Ingmar Werneburg, Naoki Morimoto, Christoph P. E. Zollikofer, Analia M. Forasiepi, Hideki Endo, Junpei Kimura, Satoshi D. Ohdachi, Nguyen Truong Son and Marcelo R. Sánchez-Villagra in Nature Communicatoins. Published online April 4 2014 doi:10.1038/ncomms4625

Mammalian skull heterochrony reveals modular evolution and a link between cranial development and brain size

The multiple skeletal components of the skull originate asynchronously and their developmental schedule varies across amniotes. Here we present the embryonic ossification sequence of 134 species, covering all major groups of mammals and their close relatives. This comprehensive data set allows reconstruction of the heterochronic and modular evolution of the skull and the condition of the last common ancestor of mammals. We show that the mode of ossification (dermal or endochondral) unites bones into integrated evolutionary modules of heterochronic changes and imposes evolutionary constraints on cranial heterochrony. However, some skull-roof bones, such as the supraoccipital, exhibit evolutionary degrees of freedom in these constraints. Ossification timing of the neurocranium was considerably accelerated during the origin of mammals. Furthermore, association between developmental timing of the supraoccipital and brain size was identified among amniotes. We argue that cranial heterochrony in mammals has occurred in concert with encephalization but within a conserved modular organization.

“Mammalian skull heterochrony reveals modular evolution and a link between cranial development and brain size” by Daisuke Koyabu, Ingmar Werneburg, Naoki Morimoto, Christoph P. E. Zollikofer, Analia M. Forasiepi, Hideki Endo, Junpei Kimura, Satoshi D. Ohdachi, Nguyen Truong Son and Marcelo R. Sánchez-Villagra in Nature Communications, April 4 2014 doi:10.1038/ncomms4625.