Small numbers are processed in the right side of the brain, while large numbers are processed in the left side of the brain, new research suggests.

The study, from scientists at Imperial College London, offers new insights into the mystery of how our brains handle numbers. The findings of the research, published in the journal Cerebral Cortex, could in the future help to tailor rehabilitation techniques for patients who have suffered brain damage, such as stroke patients, and inform treatments for conditions such as dyscalculia, which causes difficulty in processing numbers.

The brain is divided into two halves – the left side controls the right half of the body, and vice versa. Generally, one side of the brain is more dominant than the other. For example, people who are right-handed tend to have more activity in the left side of their brains.

Previous studies have highlighted the general region where the brain handles numbers – in an area called the fronto-parietal cortex, which runs approximately from the top of the head to just above the ear. But scientists are in the dark about how exactly the brain unpicks and processes numbers.

However, previous observations from stroke patients, who often suffer damage to the right side of their brains, have given clues that suggest large numbers and small numbers are handled on different sides of the brain.

Dr. Qadeer Arshad, lead author of the study from the Department of Medicine at Imperial, said: “Following early insights from stroke patients we wanted to find out exactly how the brain processes numbers. In our new study, in which we used healthy volunteers, we found the left side processes large numbers, and the right processes small numbers. So for instance if you were looking at a clock, the numbers one to six would be processed on the right side of the brain, and six to twelve would be processed on the left.”

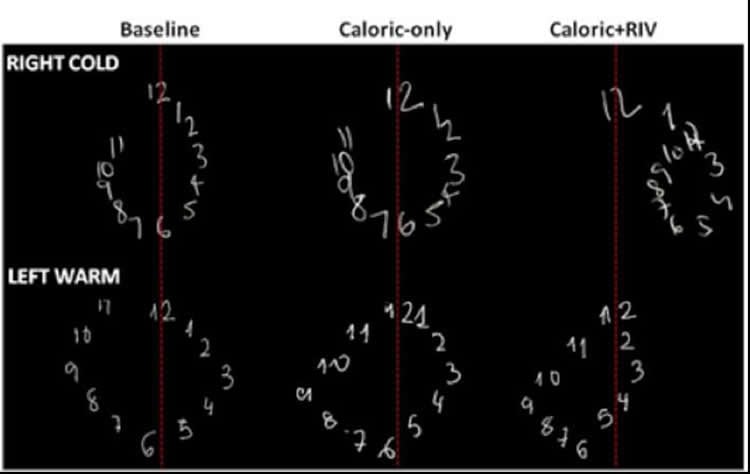

In their study, which was funded by the Medical Research Council, the team temporally deactivated either the left or right side of the brain of healthy volunteers. They did this using a complex technique – the volunteers were asked to wear goggles that showed them a picture of either a horizontal or vertical line. At the same time, the participants underwent a procedure called the caloric reflex test. This is commonly used to diagnose ear and balance disorders and involves trickling either hot or cold water into a person’s ears.

Earlier research has shown this combination activates different sides of the brain.

Volunteers then took a range of number tests. These involved saying the middle number between a number range, for instance between 22 and 76, or drawing the numbers of a clock face. “When we activated the right side of the brain, the volunteers were saying smaller numbers – for instance if we asked the middle point of 50-100, they were saying 65 instead of 75. But when we activated the left side of the brain, the volunteers were saying numbers above 75,” said Dr. Arshad.

He adds that the context of the number was crucial. “If someone was looking at a range of 50-100 then the number 80 will probably be processed on the left side of the brain. However, if they are looking at a range of 50-300, then 80 will now be small number, and processed on the right.”

After asking the volunteers to draw a clock face, the team found that when the right side of the brain was activated, the participants tended to draw the numbers 1 to 6 slightly larger and more prominent, with greater space between the numbers. When the left brain was activated, they drew 6 to 12 bigger.

Dr. Arshad adds that people tend to have one side of their brain more dominant than the other, and can test on themselves which side is more active during number processing.

“If you someone asks you to quickly name the middle number between two numbers – say 22 and 46 – and you overestimate the midpoint (34), you may have a relatively more active left side of the brain than someone who responds with 31. You can try this task a number of times with different numbers to see which side of the brain is most dominant.”

He adds that the findings from the current study may help inform treatments for individuals who struggle to process numbers.

“The findings offer a starting point for unravelling how the brain handles and represents numbers – so-called numerical cognition. If we understand how numbers are processed we may be able to target treatments and rehabilitation therapies. The next stage is to examine how the brain handles large, complex calculations.”

Funding: The study was supported by the Medical Research Council.

Source: Madeline McCurry-Schmidt – Imperial College London

Image Credit: The image is credited to Imperial College London.

Original Research: Full open access research for “Bidirectional Modulation of Numerical Magnitude” by Qadeer Arshad, Yuliya Nigmatullina, Ramil Nigmatullin, Paladd Asavarut, Usman Goga, Sarah Khan, Kaija Sander, Shuaib Siddiqui, R. E. Roberts, Roi Cohen Kadosh, Adolfo M. Bronstein, and Paresh A. Malhotra in Cerebral Cortex. Published online February 14 2016 doi:10.1093/cercor/bhv344

Abstract

Bidirectional Modulation of Numerical Magnitude

Numerical cognition is critical for modern life; however, the precise neural mechanisms underpinning numerical magnitude allocation in humans remain obscure. Based upon previous reports demonstrating the close behavioral and neuro-anatomical relationship between number allocation and spatial attention, we hypothesized that these systems would be subject to similar control mechanisms, namely dynamic interhemispheric competition. We employed a physiological paradigm, combining visual and vestibular stimulation, to induce interhemispheric conflict and subsequent unihemispheric inhibition, as confirmed by transcranial direct current stimulation (tDCS). This allowed us to demonstrate the first systematic bidirectional modulation of numerical magnitude toward either higher or lower numbers, independently of either eye movements or spatial attention mediated biases. We incorporated both our findings and those from the most widely accepted theoretical framework for numerical cognition to present a novel unifying computational model that describes how numerical magnitude allocation is subject to dynamic interhemispheric competition. That is, numerical allocation is continually updated in a contextual manner based upon relative magnitude, with the right hemisphere responsible for smaller magnitudes and the left hemisphere for larger magnitudes.

“Bidirectional Modulation of Numerical Magnitude” by Qadeer Arshad, Yuliya Nigmatullina, Ramil Nigmatullin, Paladd Asavarut, Usman Goga, Sarah Khan, Kaija Sander, Shuaib Siddiqui, R. E. Roberts, Roi Cohen Kadosh, Adolfo M. Bronstein, and Paresh A. Malhotra in Cerebral Cortex. Published online February 14 2016 doi:10.1093/cercor/bhv344