Summary: Emotion recognition extends far beyond facial expressions, involving a rich interplay of context, physical attributes, and background knowledge. Researchers propose that recognizing emotion is part of forming an overall impression of a person, shaped by cues like clothing, perceived social roles, and personal history. For instance, a facial expression of fear might be interpreted as anger if background context suggests it.

This model of emotion recognition suggests current AI emotion recognition systems may be too limited. Incorporating broader contextual cues may improve AI’s ability to interpret emotions. These insights are a step toward more accurate, human-like emotion recognition in artificial intelligence.

Key Facts:

- Emotion recognition involves context, physical cues, and personal knowledge.

- Background knowledge can shift how we interpret emotions from facial cues.

- AI emotion detection may improve by moving beyond facial expression analysis.

Source: RUB

A person’s facial expression provides crucial information for us to recognize their emotions. But there’s much more to this process than that.

This is according to the research conducted by Dr. Leda Berio and Professor Albert Newen from the Institute of Philosophy II at Ruhr University Bochum, Germany.

The team describes emotion recognition not as a separate module, but as part of a comprehensive process that helps us form a general impression of another person. This process of person impression formation also includes physical and cultural characteristics as well as background information.

The paper was published on September 24, 2024 in the journal Philosophy and Phenomenological Research.

Understanding the situation affects how we recognize emotions

In the 1970s, the theory was put forward that the face is the window to our emotions. Researcher Paul Ekman described basic emotions such as fear, anger, disgust, joy and sadness using typical facial expressions, which were found to be similar across all cultures.

“However, in recent years it’s become increasingly obvious that there are many situations in life where a typical facial expression is not necessarily the key piece of information that guides our assessment of other people’s feelings,” points out Newen and cites the following example:

“People almost universally rate a typical facial expression of fear as anger when they have the background knowledge that the assessed person’s been turned away by a waiter even though they’d demonstrably reserved a table.”

In such a situation, people expect the person to be angry, and this expectation determines the perception of their emotion, even if their facial expression would typically be attributed to a different emotion.

“In addition, we can sometimes recognize emotions even without seeing the face; for example, the fear experienced by a person who’s being attacked by a snarling dog, even though we only see them from behind in a stance of freeze or fright,” illustrates Berio.

Recognizing an emotion is part of our overall impression of a person

Berio and Newen propose that recognizing emotions is a sub-process of our ability to form an overall impression of a person. In doing so, people are guided by certain characteristics of the other person, for example physical appearance characteristics such as skin color, age and gender, cultural characteristics such as clothing and attractiveness as well as situational characteristics such as facial expression, gestures and posture.

Based on such characteristics, people tend to quickly assess others and immediately associate social status and even certain personality traits with them. These associations dictate how we perceive other people’s emotions.

“If we perceive a person as a woman and they show a negative emotion, we’re more likely to attribute the emotion to fear, whereas with a man it’s more likely to be read as anger,” as Berio points out.

Background information is included in the assessment

In addition to the perception of characteristics and initial associations, we also hold detailed person images that we use as background information for individuals in our social circle – family members, friends and colleagues.

“If a family member suffers from Parkinson’s, we learn to assess the typical facial expression of this person, which seems to indicate anger, as neutral, because we are aware that a rigid facial expression is part of the disease,” says Berio.

The background information also includes person models of typical occupational groups.

“We hold stereotypical assumptions about the social roles and responsibilities of for example doctors, students and workmen,” says Newen. “We generally perceive doctors as less emotional, for example, which changes the way we assess their emotions.”

In other words, people make use of the wealth of characteristics and background knowledge to assess the emotion of another person. Only in rare cases do they read the emotion from a person’s facial expression alone.

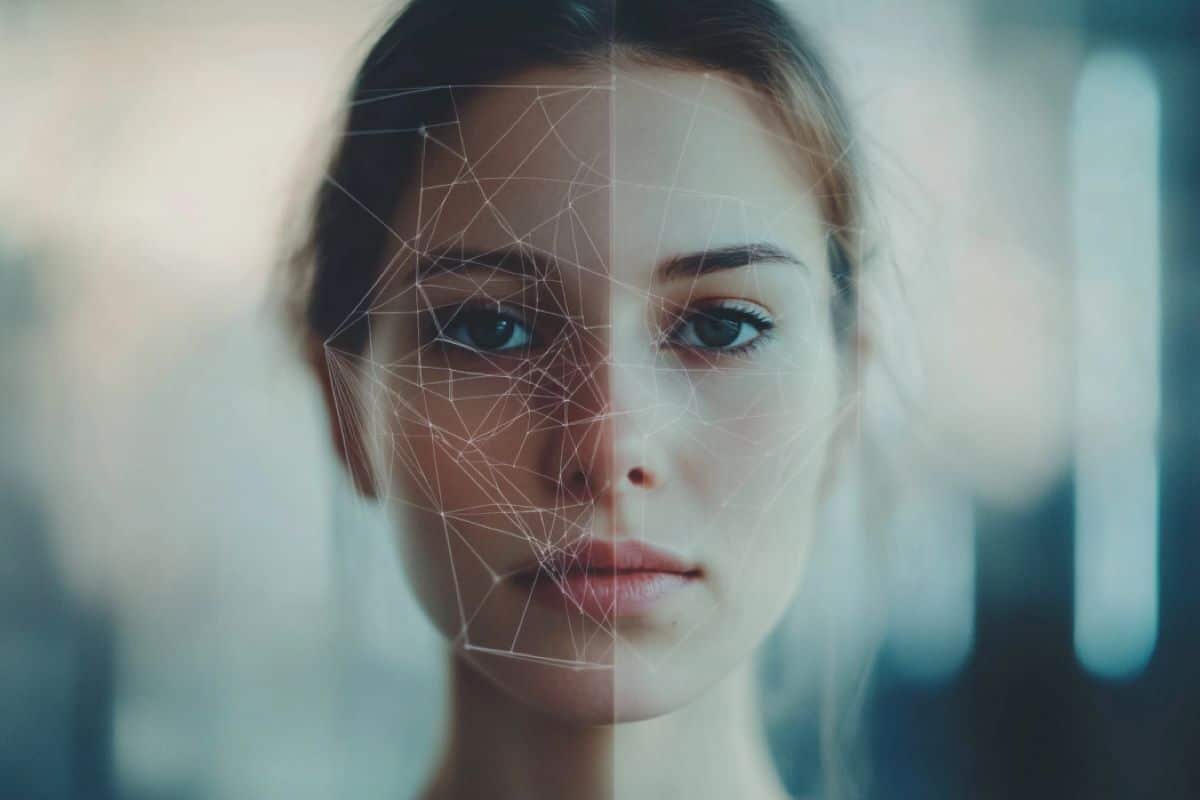

“All this has implications for emotion recognition using artificial intelligence (AI): It will only be a reliable option when AI doesn’t rely solely on facial expressions, which is what most systems currently do,” says Newen.

About this emotion, facial recognition, and AI research news

Author: Julia Weiler

Source: RUB

Contact: Julia Weiler – RUB

Image: The image is credited to Neuroscience News

Original Research: Open access.

“I Expect You to Be Happy, So I See You Smile: A Multidimensional Account of Emotion Attribution” by Albert Newen et al. Philosophy and Phenomenological Research

Abstract

I Expect You to Be Happy, So I See You Smile: A Multidimensional Account of Emotion Attribution

Constructivist theories of emotions and empirical studies have been increasingly stressing the role of contextual information and cultural conventions in emotion recognition.

We propose a new account of emotion recognition and attribution that systematically integrates these aspects, and argue that emotion recognition is part of the general process of person impression formation.

To describe the structural organization and the role of background information in emotion recognition and attribution, we introduce situation models and personal models.

These models constitute the top-level structures in a complex hierarchy of dimensions which considers different types of basic emotion cues.

Thus, we propose a multidimensional account of emotion recognition which enables us to integrate the top-down and bottom-up processes involved: basic emotion cues in certain contexts can trigger situation models and person models, which influence emotion recognition which, in turn, reinforce or modify these models.

We argue that this kind of loop deeply affects the way emotions enter our social interactions. Our account is in line with the “normative turn” of social cognition, that stresses the way social expectations actively shape the patterns we recognize, and make, in our social world.