Summary: People with behavioral variant frontotemporal dementia (bvFTD) exhibit behaviors that are considered socially unacceptable. While there is no current cure for FTD, researchers are finding methods to help inhibit some of the negative behaviors associated with FTD. A new study reports impulsivity and negative behaviors are greatly reduced in those with bvFTD when the patient is focused on a task.

Source: Paris Brain Institute

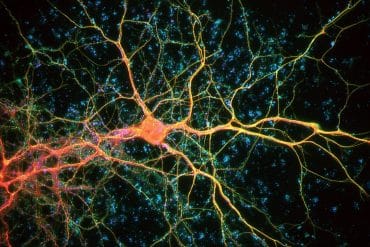

Disinhibition is one of the main symptoms of the behavioral variant frontotemporal dementia (bvFTD), a type of dementia associated with degeneration of the frontal and temporal lobes of the brain. Patients with bvFTD exhibit behaviors that are considered inappropriate, to the point that caregivers and family members may feel helpless.

Thanks to the ECOCAPTURE study conducted at the Brain Institute by Bénédicte Batrancourt, Richard Levy and Lara Migliaccio (Inserm, CNRS, Sorbonne Universities, AP-HP), new avenues are emerging to distinguish different types of disinhibition on which it is possible to intervene without resorting to medication. This could lead to improved care and reduce the isolation of patients and their caregivers.

The results of the study are published in the journal Cortex.

The behavioral variant of frontotemporal dementia (bvFTD), like other types of dementia, is marked by a progressive decline in cognitive function. But it is also characterized by severe brain atrophy and the presence of abnormal protein deposits inside neurons. The effects of bvFTD on behavior are particularly pronounced, and even more troubling as they appear in subjects who are still young and active—between 45 and 65 years old.

Changes in personality expression, apathy, impaired judgment and empathy, inappropriate conduct: the symptoms are difficult to manage since patients are not aware of their disease, and do not perceive its effects on those around them.

“Frontotemporal dementia needs to surface from invisibility. Because patients are not able to seek care, which is common in neurobehavioral diseases, they don’t really have a voice of their own,” Migliaccio said. “As for caregivers, they often feel at loss because patients are young and rarely have co-morbidities. Nursing homes or hospitals are not appropriate places for them.”

Currently, there is no specific treatment for bvFTD. Sometimes confused with other disorders, such as Alzheimer’s disease, bvFTD is even more difficult to identify when the behavior of patients is a source of taboo in the family environment.

For all these reasons, the disease remains poorly understood—as well as disinhibition, one of its key symptoms. Because the manifestations of disinhibition can be specific to each individual and vary according to the environment and social situations, researchers must study them in a realistic framework, what we call an “ecological” approach.

Expression of disinhibition in context

This is the purpose of the work carried out by Lara Migliaccio and Bénédicte Batrancourt at Paris Brain Institute, within the FrontLab team led by Richard Levy. In collaboration with colleagues at the University of Rennes, researchers recruited 23 bvFTD patients and 24 healthy volunteers at Pitié-Salpêtrière Hospital in Paris.

They studied the behavior of each individual in the same scenario: the participants had to wait, alone, in a furnished room resembling a medical waiting room—equipped with invisible cameras.

For 45 minutes, they were invited to explore the room and interact freely with the objects dispatched within it (games, magazines, food, drinks, scales, pens, etc.). In the last part of the experiment, participants were given a questionnaire which required them to explore specific aspects of the room to complete the various questions.

With this scenario, designed to encourage the emergence of unexpected initiatives, the team observed a variety of disinhibited behaviors in both the bvFTD and control groups.

They classified them into three categories: Compulsivity, which includes repeated movements or inappropriate perseveration (opening and closing the window with no particular purpose, rubbing hands continuously, insisting on turning on a tap that doesn’t work… ), impulsivity, marked by the emergence of impulses or strong emotions (shouting, laughing, dancing…) and social disinhibition, in which the participant does not respect implicit social codes of communication with others (non-compliance of the experimenter’s instructions, excessive familiarity, insults…).

This classification allowed the researchers to objectively measure the effects of a third-party intervention on the different components of disinhibition. Their results first indicate that, believing themselves to be alone, all participants showed some level of disinhibition. This was much more pronounced in the bvFTD patients than in the control group, particularly regarding social disinhibition.

This finding supports the idea that disinhibited behaviors exist along a spectrum, and that it is simply their intensity and frequency that defines their pathological nature in frontotemporal dementia.

Toward personalized approaches

The researchers also noted that bvFTD patients tended to remain idle if they were not actively encouraged to perform an action. The higher their activity level, the lower their symptoms of social disinhibition. Finally, their level of impulsivity was greatly reduced when they were focused on a task, such as completing the questionnaire requested by the examiner.

Stimulation techniques adapted to each patient (games, puzzles, physical activity…) could therefore constitute an efficient non-medicinal approach to reduce frustration and agitation in these patients. Though they are the first to suffer from it, it also affects caregivers and relatives greatly.

These results must now be reproduced on a larger number of patients. Researchers will also have to assess the duration of the benefits induced by the intervention of the caregivers. Indeed, people affected by bvFTD tend to feel more stress when their environment requires cognitive performances that they are not capable of. Inappropriate or intense stimulation could reinforce their symptoms, rather than alleviate them.

The authors thus suggest that activities that correspond to pre-existing hobbies, or familiar household tasks (cooking, gardening…) would be most likely to provide significant benefit.

“The next step will be to understand patients’ behavior in even greater detail,” Batrancourt says.

“The future ECOCAPTURE@HOME program will make it possible to measure variations in their activity level, quality of sleep and emotions according to changes in their environment, at home, thanks to a smart watch.

“The goal is, in the long run, to personalize care management so that their symptoms can be managed as efficiently and as long as possible at home, as well as reducing any taboo surrounding the disease.”

About this frontotemporal dementia research news

Author: Marie Simon

Source: Paris Brain Institute

Contact: Marie Simon – Paris Brain Institute

Image: The image is in the public domain

Original Research: Open access.

“Behavioural disinhibition in frontotemporal dementia investigated within an ecological framework” by Delphine Tanguy et al. Cortex

Abstract

Behavioural disinhibition in frontotemporal dementia investigated within an ecological framework

Disinhibition is a core symptom in behavioural variant frontotemporal dementia (bvFTD) particularly affecting the daily lives of both patients and caregivers. Yet, characterisation of inhibition disorders is still unclear and management options of these disorders are limited. Questionnaires currently used to investigate behavioural disinhibition do not differentiate between several subtypes of disinhibition, encompass observation biases and lack of ecological validity.

In the present work, we explored disinhibition in an original semi-ecological situation, by distinguishing three categories of disinhibition: compulsivity, impulsivity and social disinhibition. First, we measured prevalence and frequency of these disorders in 23 bvFTD patients and 24 healthy controls (HC) in order to identify the phenotypical heterogeneity of disinhibition. Then, we examined the relationships between these metrics, the neuropsychological scores and the behavioural states to propose a more comprehensive view of these neuropsychiatric manifestations. Finally, we studied the context of occurrence of these disorders by investigating environmental factors potentially promoting or reducing them.

As expected, we found that patients were more compulsive, impulsive and socially disinhibited than HC. We found that 48% of patients presented compulsivity (e.g., repetitive actions), 48% impulsivity (e.g., oral production) and 100% of the patients group showed social disinhibition (e.g., disregards for rules or investigator). Compulsivity was negatively related with emotions recognition. BvFTD patients were less active if not encouraged in an activity, and their social disinhibition decreased as activity increased. Finally, impulsivity and social disinhibition decreased when patients were asked to focus on a task.

Summarising, this study underlines the importance to differentiate subtypes of disinhibition as well as the setting in which they are exhibited, and points to stimulating area for non-pharmacological management.