Summary: The writing system with which we learn to read may influence how we process speech, researchers report. Findings suggest the ability to write influences the way in which our brains process language.

Source: University of Zurich

Do people who can read and write understand spoken language better than those who are illiterate?

Research carried out by a UZH researcher with collaborators in India has found that handwriting, specifically the type of writing system used for a language, influences how our brains process speech.

The study is published in The Journal of Neuroscience.

When we learn to read, connections are developed between the visual system and the language system in our brain. The symbols we see on the page become associated with sounds and meanings. It seems logical, therefore, that our ability to read and write would affect our auditory processing of speech.

An international team including researchers from UZH has now investigated this question in greater depth.

While previous studies focused on alphabetic writing systems in which individual symbols stand for consonants and vowels, in the new study the researchers turned their attention to non-alphabetic writing systems.

“In the Middle East, East Africa, or South and East Asia, many people read and write languages in which the individual symbols represent syllables or even whole words,” says Alexis Hervais-Adelman, professor of neurolinguistics at the University of Zurich.

“We wanted to know whether learning a non-alphabetic script has the same effects on the brain as alphabetic languages.”

No link between literacy and improved auditory understanding

Together with the Max Planck Institute for Psycholinguistics in Nijmegen in the Netherlands and a team in Uttar Pradesh in northern India, the Zurich researchers played recorded sentences in Hindi to two groups of study participants: people who could read and write, and people who were illiterate. At the same time, their brain responses were observed via MRI.

Hindi is written with a non-alphabetic script called Devanagari. The researchers found that the auditory systems of the literate group reacted no differently from those of illiterate people.

This result contradicts findings from previous studies which focused on alphabetic reading and concluded that reading ability led to increased activity in those brain areas responsible for language processing when people hear speech.

“Our findings are significant, as they challenge previous assumptions about the effects of reading and writing on our brains and on how we process spoken language,” says first author Hervais-Adelman.

“The writing system with which we learn to read may influence the way in which we process speech.”

Writing influences language processing

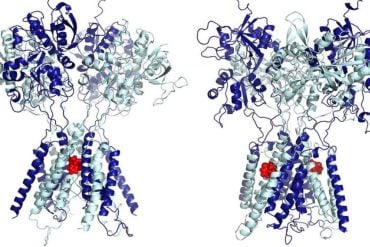

Although there was no difference in auditory processing, the researchers did find evidence that those able to read and write Devanagari had improved functional connectivity between the graphomotor brain areas responsible for handwriting and the auditory-phonetic brain areas that process speech sounds. These connections became active when the group who could read and write Devanagari listened to the Hindi recordings.

According to the researchers, this suggests that the ability to write, rather than reading skills per se, also influences the way our brains process language. More intensive research into this link in the future could lead to the development of new treatments for dyslexia, focusing on the relationship between writing and listening.

About this language and speech research news

Author: Press Office

Source: University of Zurich

Contact: Press Office – University of Zurich

Image: The image is in the public domain

Original Research: Closed access.

“How does literacy affect speech processing? Not by enhancing cortical responses to speech, but by promoting connectivity of acoustic-phonetic and graphomotor cortices” by Alexis Hervais-Adelman et al. Journal of Neuroscience

Abstract

How does literacy affect speech processing? Not by enhancing cortical responses to speech, but by promoting connectivity of acoustic-phonetic and graphomotor cortices

Previous research suggests that literacy, specifically learning alphabetic letter-to-phoneme mappings, modifies online speech processing, and enhances brain responses, as indexed by the blood-oxygenation level dependent signal (BOLD), to speech in auditory areas associated with phonological processing (Dehaene et al., 2010).

However, alphabets are not the only orthographic systems in use in the world, and hundreds of millions of individuals speak languages that are not written using alphabets.

In order to make claims that literacy per se has broad and general consequences for brain responses to speech, one must seek confirmatory evidence from non-alphabetic literacy. To this end, we conducted a longitudinal fMRI study in India probing the effect of literacy in Devanagari, an abubgida, on functional connectivity and cerebral responses to speech in 91 variously literate Hindi-speaking male and female human participants.

Twenty-two completely illiterate participants underwent six months of reading and writing training. Devanagari literacy increases functional connectivity between acoustic-phonetic and graphomotor brain areas, but we find no evidence that literacy changes brain responses to speech, either in cross-sectional or longitudinal analyses.

These findings shows that a dramatic reconfiguration of the neurofunctional substrates of online speech processing may not be a universal result of learning to read, and suggest that the influence of writing on speech processing should also be investigated.