Summary: Researchers discovered that wildfire smoke can trigger long-lasting inflammation in the brain. Their study shows that this inflammation specifically targets the hippocampus, a brain area crucial for learning and memory.

Using rodents exposed to wood smoke, the scientists identified changes in neurotransmitters and signaling molecules in the brain that lasted for over a month. The findings highlight an urgent concern for populations regularly exposed to wildfire smoke, including older adults and those with respiratory conditions.

Key Facts:

- Wildfire smoke can induce inflammation in the brain that persists for more than a month.

- The study found the hippocampus is particularly affected, risking long-term damage to learning and memory.

- The research reveals that intermittent, rather than constant, exposure to smoke might pose a more serious risk due to surges in inflammatory activity.

Source: University of New Mexico

Smoke from the massive wildfires still burning in northern Canada has cast a pall over much of North America this summer, leading to health concerns for older people and those with chronic respiratory conditions.

But a new paper published in the Journal of Neuroinflammation by University of New Mexico Health Sciences scientists gives new cause for alarm, finding that wildfire smoke can trigger inflammation in the brain that persists for a month or more.

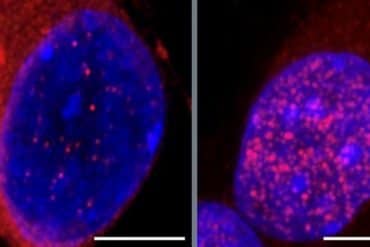

Worse, the inflammatory process affects the hippocampus – the brain region associated with learning and memory – altering neurotransmitters and signaling molecules, said the paper’s senior author, Matthew Campen, PhD, Regents’ professor in the College of Pharmacy and co-director of the UNM Clinical & Translational Science Center.

The research was led by David Scieszka, PhD, a postdoctoral student in Campen’s laboratory who exposed rodents to wood smoke every other day for two weeks. “We were trying to figure out if the stuff we saw in the wild could at least be partially figured out in the lab,” he said.

The team identified both pro- and anti-inflammatory responses as tiny particles from the smoke entered the circulation from the lungs and crossed the blood-brain barrier, a layer of tightly packed cells lining blood vessels in the brain.

“We were able to measure the inflammatory response amplitude and time frames,” Scieszka said.

“We expected it to be a lot shorter. Some of it progressed out to 28 days and we didn’t see a complete resolution, and that was very scary to us.”

The blood-brain barrier cells had had largely adapted to the smoke exposure by Day 14, but the immune cells in the brain remained abnormally activated, he said.

Campen said the findings are concerning given how many people are now regularly exposed to wildfire smoke.

“Neuroinflammation is the seed for all sorts of bad things in the brain, including dementia, Alzheimer’s disease – the buildup of the plaques – but also alterations in neurodevelopment in early life and mood disorders throughout life,” he said.

“If you’re a firefighter, or if you’re just a citizen in a community that has had some of these dramatic smoke exposures, you could be having neurocognitive or mood disorders weeks or months or weeks after the event.”

With heavy concentrations of wildfire smoke, people should remain inside if they can, Campen said.

“Houses have varying penetrance of particulates. If you’ve got an evaporative cooler, you’re just being exposed to the outdoor air, but a lot of houses will be much more protective.” N-95 masks offer protection to those who venture outside, he added.

The human body seems capable of adapting to chronic particulate exposure to an extent, Campen said. But periodic exposures pose a problem because they cause a surge in inflammatory activity, and ill effects appear more related to the fluctuations, rather than the baseline levels of pollutants.

“Part of what makes this so unique and worrisome is the intermittent nature of it,” he said. “We have rural communities that are otherwise enjoying clean beautiful air, especially in the Rocky Mountain region, and then all of a sudden they have suffocating levels of pollutants and it’s gone a week later. It’s a real hit to a naïve system.”

About this neuroinflammation and environmental neuroscience research news

Author: Chris Ramirez

Source: University of New Mexico

Contact: Chris Ramirez – University of New Mexico

Image: The image is credited to Neuroscience News

Original Research: Open access.

“Biomass smoke inhalation promotes neuroinflammatory and metabolomic temporal changes in the hippocampus of female mice” by Matthew Campen et al. Journal of Neuroinflammation

Abstract

Biomass smoke inhalation promotes neuroinflammatory and metabolomic temporal changes in the hippocampus of female mice

Smoke from wildland fires has been shown to produce neuroinflammation in preclinical models, characterized by neural infiltrations of neutrophils and monocytes, as well as altered neurovascular endothelial phenotypes.

To address the longevity of such outcomes, the present study examined the temporal dynamics of neuroinflammation and metabolomics after inhalation exposures from biomass-derived smoke. 2-month-old female C57BL/6 J mice were exposed to wood smoke every other day for 2 weeks at an average exposure concentration of 0.5 mg/m3. Subsequent serial euthanasia occurred at 1-, 3-, 7-, 14-, and 28-day post-exposure.

Flow cytometry of right hemispheres revealed two endothelial populations of CD31Hi and CD31Med expressors, with wood smoke inhalation causing an increased proportion of CD31Hi.

These populations of CD31Hi and CD31Med were associated with an anti-inflammatory and pro-inflammatory response, respectively, and their inflammatory profiles were largely resolved by the 28-day mark.

However, activated microglial populations (CD11b+/CD45low) remained higher in wood smoke-exposed mice than controls at day 28. Infiltrating neutrophil populations decreased to levels below controls by day 28.

However, the MHC-II expression of the peripheral immune infiltrate remained high, and the population of neutrophils retained an increased expression of CD45, Ly6C, and MHC-II.

Utilizing an unbiased approach examining the metabolomic alterations, we observed notable hippocampal perturbations in neurotransmitter and signaling molecules, such as glutamate, quinolinic acid, and 5-α-dihydroprogesterone.

Utilizing a targeted panel designed to explore the aging-associated NAD+ metabolic pathway, wood smoke exposure drove fluctuations and compensations across the 28-day time course, ending with decreased hippocampal NAD+ abundance on day 28.

Summarily, these results indicate a highly dynamic neuroinflammatory environment, with potential resolution extending past 28 days, the implications of which may include long-term behavioral changes, systemic and neurological sequalae directly associated with wildfire smoke exposure.