Those with borderline personality disorder, or BPD, a mental illness marked by unstable moods, often experience trouble maintaining interpersonal relationships. New research from the University of Georgia indicates that this may have to do with lowered brain activity in regions important for empathy in individuals with borderline personality traits.

The findings were recently published in the journal Personality Disorders: Theory, Research and Treatment.

“Our results showed that people with BPD traits had reduced activity in brain regions that support empathy,” said the study’s lead author Brian Haas, an assistant professor in the Franklin College of Arts and Sciences psychology department. “This reduced activation may suggest that people with more BPD traits have a more difficult time understanding and/or predicting how others feel, at least compared to individuals with fewer BPD traits.”

For the study, Haas recruited over 80 participants and asked them to take a questionnaire, called the Five Factor Borderline Inventory, to determine the degree to which they had various traits associated with borderline personality disorder. The researchers then used functional magnetic resonance imaging to measure brain activity in each of the participants. During the fMRI, participants were asked to do an empathetic processing task, which tapped into their ability to think about the emotional states of other people, while the fMRI measured their simultaneous brain activity.

In the empathetic processing task, participants would match the emotion of faces to a situation’s context. As a control, Haas and study co-author Joshua Miller also included shapes, like squares and circles, that participants would have to match from emotion of the faces to the situation.

“We found that for those with more BPD traits, these empathetic processes aren’t as easily activated,” said Miller, a psychology professor and director of the Clinical Training Program.

Haas chose to look at those who scored high on the Five Factor Borderline Inventory, instead of simply working with those previously diagnosed with the disorder. By using the inventory, Haas was able to obtain a more comprehensive understanding of the relationship between empathic processing, BPD traits and high levels of neuroticism and openness, as well as lower levels of agreeableness and conscientiousness.

“Oftentimes, borderline personality disorder is considered a binary phenomenon. Either you have it or you don’t,” said Haas, who runs the Gene-Brain-Social Behavioral Lab. “But for our study, we conceptualized and measured it in a more continuous way such that individuals can vary along a continuum of no traits to very many BPD traits.”

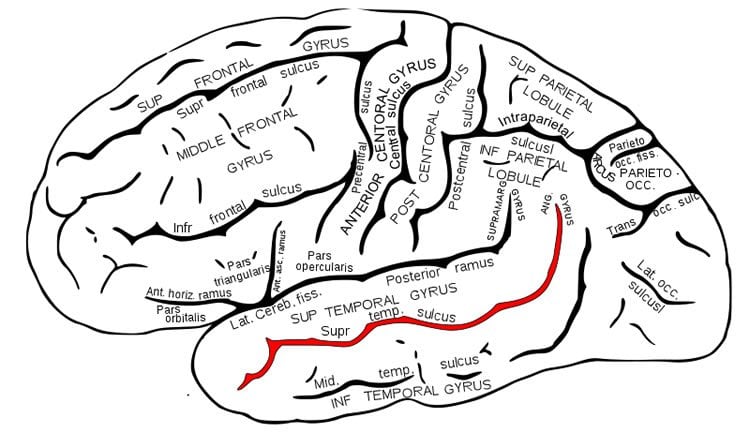

Haas found a link between those with high borderline personality traits and a decreased use of neural activity in two parts of the brain: the temporoparietal junction and the superior temporal sulcus, two brain regions implicated to be critically important during empathic processing.

The research provides new insight into individuals susceptible to experiencing the disorder and how they process emotions.

“Borderline personality disorder is considered one of the most severe and troubling personality disorders,” Miller said. “BPD can make it difficult to have successful friendships and romantic relationships. These findings could help explain why that is.”

In the future, Haas would like to study BPD traits in a more naturalistic setting.

“In this study, we looked at participants who had a relatively high amount of BPD traits. I think it’d be great to study this situation in a real life scenario, such as having people with BPD traits read the emotional states of their partners,” he said.

Source: Molly Berg – UGA

Image Source: The image is in the public domain

Original Research: Abstract for “Borderline Personality Traits and Brain Activity During Emotional Perspective Taking” by Haas, Brian W.; and Miller, Joshua D. in Personality Disorders: Theory, Research and Treatment. Published online July 13 2015 doi:10.1037/per0000130

Abstract

Borderline Personality Traits and Brain Activity During Emotional Perspective Taking

Borderline personality disorder (BPD) is characterized by disturbances in emotional, behavioral, and social functioning. The relation between BPD and empathy, which may affect the functional difficulties associated with this disorder, is complex because there is some evidence of heighted empathic processing and some evidence of reduced empathic processing in BPD. The current study was designed to investigate the association between BPD traits and brain activity during an empathic processing task (emotion perspective taking) in a nonclinical sample (N = 82). Participants completed the Five-Factor Borderline Inventory and underwent functional MRI while conducting an emotional perspective-taking task. Higher BPD trait scores were associated with hypoactivity in two brain regions involved in cognitive empathy (superior temporal sulcus and the temporoparietal junction). These data provide support to existing models describing the heterogeneous nature of BPD and suggest that reduced neural activity may in part affect altered empathic processing in BPD.

“Borderline Personality Traits and Brain Activity During Emotional Perspective Taking” by Haas, Brian W.; and Miller, Joshua D. in Personality Disorders: Theory, Research and Treatment. Published online July 13 2015 doi:10.1037/per0000130