Summary: Communication between the medial temporal lobe and prefrontal cortex determines how our experiences become memories. As the brain areas mature, the precise way they interact allows for the better formation of long-term memory.

Source: Wayne State University

A research team led by faculty members at Wayne State University has discovered that communication between two key memory regions in the brain determines how what we experience becomes part of what we remember, and as these regions mature, the precise ways by which they interact make us better at forming lasting memories.

The study, “Dissociable oscillatory theta signatures of memory formation in the developing brain,” was published in the Feb. 15 issue of Current Biology.

According to the researchers, it has long been suspected that interactions between the medial temporal lobe (MTL) and prefrontal cortex (PFC), two regions of the brain that play a key role in supporting memory formation, are responsible for the robust increase in memory capacity between childhood and adulthood. To understand the nature of these interactions, they examined rare electrocorticographic (ECoG) data recorded simultaneously from MTL and PFC in neurosurgical patients, children and adults, who were trying to memorize pictures of scenes. With these unique data, the researchers examined how MTL-PFC interactions support memory development.

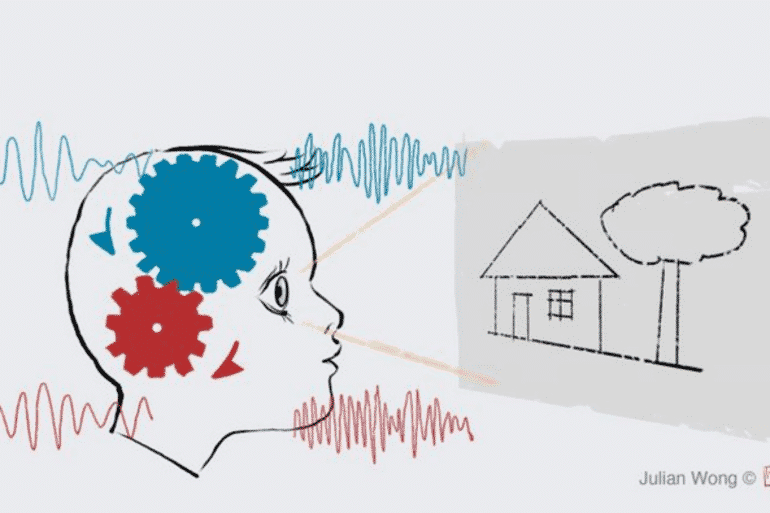

“We started by identifying two distinct brain signals – oscillations that one can think of as fluctuations in coordinated electrical brain activity, both in the theta frequency, a slower (~3 Hz) and a faster (~7 Hz) theta – that underlie memory formation in the MTL. We then continued to isolate unique effects that these fast and slow theta oscillations play in MTL-PFC interactions,” said Noa Ofen, Ph.D., associate professor of psychology in the College of Liberal Arts and Sciences and faculty member in the Institute of Gerontology, Merrill Palmer Skillman Institute, and Translational Neuroscience Program at Wayne State. “We found that both oscillations underlined MTL-PFC interactions but in complementary unique ways and were excited to also find that these distinct signatures of interactions between memory regions dictated whether a memory was successfully formed.”

The team then asked if those signatures of MTL-PFC interactions directly explain better memory in older compared to younger individuals, and indeed, they discovered that MTL-PFC interactions immediately preceding scene onset differentiated top-performing adolescents from lower-performing adolescents and children, thereby showing direct relations to memory development.

Another finding in the study is that there appears to be age differences in fast and slow theta oscillations – the slow theta frequency slows down with age, and the fast gets faster. This is a critical novel finding that has potentially vast implications for understanding brain development and understanding age-related differences in recognition performance.

Curious about the underlying anatomical infrastructure that gives rise to interactions that support memory, the team paired their findings with diffusion-weighted MRI data from a subset of subjects. They discovered that the neurophysiological signatures of memory development were linked to the structural maturation of a specific white matter tract – the cingulum.

“Putting the pieces together, this research reveals that key memory regions interact via two increasingly dissociable mechanisms as memory improves with age,” said Elizabeth Johnson, Ph.D., assistant professor of medical social sciences and pediatrics at Northwestern University.

“Findings suggest that the development of memory is rooted in the development of the brain’s ability to multitask – here, coordinate distinct slow and fast theta networks along the same tract. This tells us something fundamental about how memory becomes what it is.”

The lead authors of the study are Elizabeth L. Johnson, Ph.D., former Wayne State post-doc and assistant professor of medical social sciences and pediatrics at Northwestern University and Noa Ofen, Ph.D., associate professor of psychology and faculty member in the Institute of Gerontology, Merrill Palmer Skillman Institute, and the Translational Neuroscience Program, Wayne State University. Other co-authors are Wayne State University graduate students Qin Yin and Nolan O’Hara; Wayne State University postdoctoral student Dr. Lingfei Tang; and Dr. Eishi Asano and Dr. Justin Jeong, Departments of Pediatrics and Neurology, Wayne State University School of Medicine and Children’s Hospital of Michigan.

Funding: This research was funded by grants from the National Institutes of Health (NIMH R01MH107512, NINDS R00NS115918, NINDS R01NS64033, and NINDS R01089659.

About this memory research news

Author: Julie O’Connor

Source: Wayne State University

Contact: Julie O’Connor – Wayne State University

Image: The image is credited to Julian Wong

Original Research: Open access.

“Dissociable oscillatory theta signatures of memory formation in the developing brain” by Noa Ofen et al. Current Biology

Abstract

Dissociable oscillatory theta signatures of memory formation in the developing brain

Highlights

- Pediatric ECoG reveals how key memory regions interact during memory formation

- Slow and fast theta frequencies differentiate by age in a double dissociation

- Medial temporal and prefrontal regions are coupled through distinct mechanisms

- Strengthened coupling and cingulum tract integrity predict age-related memory gains

Summary

Understanding complex human brain functions is critically informed by studying such functions during development. Here, we addressed a major gap in models of human memory by leveraging rare direct electrophysiological recordings from children and adolescents. Specifically, memory relies on interactions between the medial temporal lobe (MTL) and prefrontal cortex (PFC), and the maturation of these interactions is posited to play a key role in supporting memory development.

To understand the nature of MTL-PFC interactions, we examined subdural recordings from MTL and PFC in 21 neurosurgical patients aged 5.9–20.5 years as they performed an established scene memory task. We determined signatures of memory formation by comparing the study of subsequently recognized to forgotten scenes in single trials.

Results establish that MTL and PFC interact via two distinct theta mechanisms, an ∼3-Hz oscillation that supports amplitude coupling and slows down with age and an ∼7-Hz oscillation that supports phase coupling and speeds up with age. Slow and fast theta interactions immediately preceding scene onset further explained age-related differences in recognition performance. Last, with additional diffusion imaging data, we linked both functional mechanisms to the structural maturation of the cingulum tract.

Our findings establish system-level dynamics of memory formation and suggest that MTL and PFC interact via increasingly dissociable mechanisms as memory improves across development.