Summary: Researchers have identified a mechanism by which neurons communicate via intonations.

Source: Marine Biological Laboratory

The dialogue between neurons is of critical importance for all nervous system activities, from breathing to sensing, thinking to running. Yet neuronal communication is so fast, and at such a small scale, that it is exceedingly difficult to explain precisely how it occurs.

A preliminary observation in the Neurobiology course at the Marine Biological Laboratory (MBL), enabled by a custom imaging system, has led to a clear understanding of how neurons communicate with each other by modulating the “tone” of their signal, which previously had eluded the field.

The report, led by Grant F. Kusick and Shigeki Watanabe of Johns Hopkins University School of Medicine, is published this week in Nature Neuroscience.

In 2016 Watanabe, then on the Neurobiology course faculty, introduced students to the debate over how many synaptic vesicles can fuse in response to one action potential (see this 2-minute video for a quick brush-up on neurotransmission).

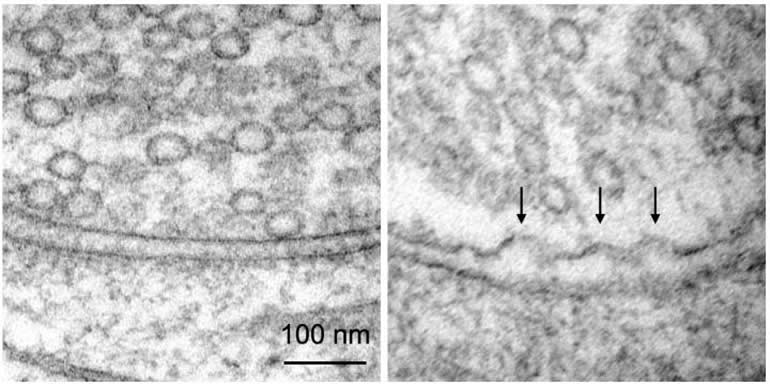

To probe this controversy, they used a “zap-and-freeze” imaging technology conceived by co-authors M. Wayne Davis, Watanabe and Erik Jorgensen, and built by Leica for testing in the Neurobiology course. They zapped a neuron with electricity to induce an action potential, then quickly froze the neuron and took an image. They saw multiple vesicles fusing at once at many synapses, the first novel finding of this Nature Neuroscience report.

But there was more. Back at Johns Hopkins, Kusick and Watanabe decided to walk through the neurotransmission process with zap-and-freeze, taking images every 3 milliseconds after the action potential. That’s when they found an answer to an even larger question – how do neurons change the tone of their neurotransmission signal?

At any given time, only a few synaptic vesicles are in “docked” position, meaning loaded and ready to release neurotransmitter. Immediately after an action potential, the number of docked vesicles decreases by 40 percent, so after 2 to 3 action potentials, the docked vesicles would be depleted. (That is, their signal or “voice” would become weaker and weaker, as more action potentials are induced.)

But they found that, within 14 milliseconds following an action potential, new vesicles are swiftly recruited to the docked pool that can fuse and release neurotransmitter, and this recruitment is transient such that neurotransmission can be strong or weak on a millisecond time scale. This is the first close-up look at neural communication that adds up from a temporal perspective.

“What this means is that we have identified a mechanism that neurons use to communicate through intonations,” Watanabe says.

“Each docked vesicle is like a word that neurons can use for communication at any given moment. It has been known for decades that neurons can speak more than a few words at a time, and they can also change the tone of these words. The question was how. We’ve shown that neurons continuously bring in more words, but by simply changing the number of vesicles, they can raise or lower the voice. If you are asking a question, you will raise the intonation at the end of a sentence – neurons do so by changing the number of docked vesicles ready to go.”

The “zap and freeze” electron microscopy technology is the 21st-century version of the “freeze slammer” developed by John Heuser, Tom Reese et al., and used at MBL nearly 50 years ago to demonstrate how neurons communicate with each other.

The MBL Neurobiology course faculty and students co-authoring this paper include Jorgensen and Davis (University of Utah), Kristina Lippmann (University of Leipzg), Kandidia P. Adula (University of California, Los Angeles), and Edward J. Hujber and Thien Vu (University of Utah). Watanabe, who was a 2014 Grass Fellow at the MBL, returns nearly annually to teach in the Neurobiology course and as a Whitman Center scientist.

About this neuroscience research article

Source:

Garvan Institute of Medical Research

Contacts:

Diana Kenney – Marine Biological Laboratory

Image Source:

The image is credited to MBL Neurobiology course/ K. Lippmann, K. Adula, T. Vu and E. Hujber.

Original Research: Closed access

“Synaptic vesicles transiently dock to refill release sites” by Grant F. Kusick, Morven Chin, Sumana Raychaudhuri, Kristina Lippmann, Kadidia P. Adula, Edward J. Hujber, Thien Vu, M. Wayne Davis, Erik M. Jorgensen & Shigeki Watanabe. Nature Neuroscience.

Abstract

Synaptic vesicles transiently dock to refill release sites

Synaptic vesicles fuse with the plasma membrane to release neurotransmitter following an action potential, after which new vesicles must ‘dock’ to refill vacated release sites. To capture synaptic vesicle exocytosis at cultured mouse hippocampal synapses, we induced single action potentials by electrical field stimulation, then subjected neurons to high-pressure freezing to examine their morphology by electron microscopy. During synchronous release, multiple vesicles can fuse at a single active zone. Fusions during synchronous release are distributed throughout the active zone, whereas fusions during asynchronous release are biased toward the center of the active zone. After stimulation, the total number of docked vesicles across all synapses decreases by ~40%. Within 14 ms, new vesicles are recruited and fully replenish the docked pool, but this docking is transient and they either undock or fuse within 100 ms. These results demonstrate that the recruitment of synaptic vesicles to release sites is rapid and reversible.