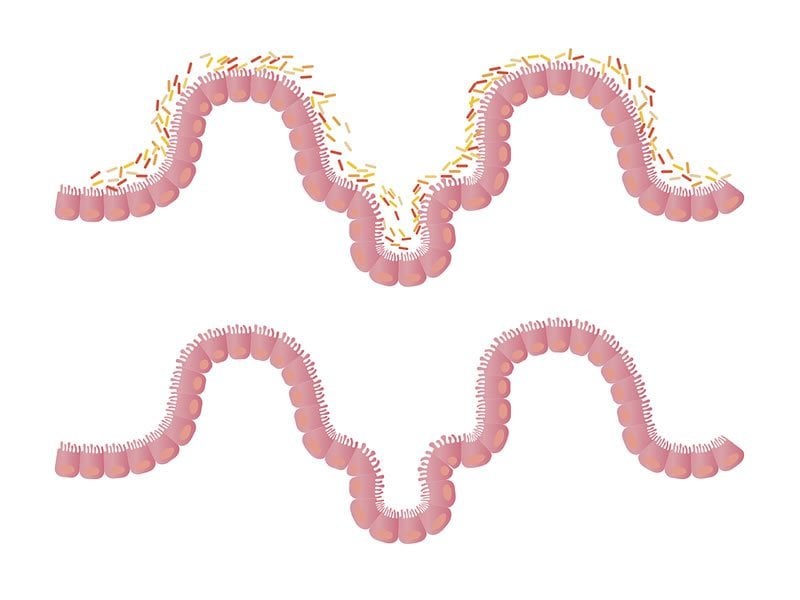

Summary: Despite humans sharing a close genetic relationship to apes, our gut microbiome more closely resembles that of Old World monkeys like baboons. In terms of the development of the human microbiome, ecology across evolution plays a more significant role than genetic relationships.

Source: Northwestern University

A new Northwestern University study finds that despite human’s close genetic relationship to apes, the human gut microbiome is more similar to that of Old World monkeys like baboons than to that of apes like chimpanzees.

These results suggest that human ecology has had a stronger impact in shaping the human gut microbiome than genetic relationships. The results also suggest the human gut microbiome may have unique characteristics compared to other primates, including increased flexibility.

“Understanding what factors shaped the human gut microbiome over evolutionary time can help us understand how gut microbes may have influenced adaptation and evolution in our ancestors and how they interact with our biology and health today,” said Katherine Amato, lead author of the study and assistant professor of anthropology in the Weinberg College of Arts and Sciences at Northwestern.

Host ecology is what drives gut microbiome composition and function, and chimpanzees have very different habitats, diets and physiologies than humans, Amato said.

“We need to look to primates with similar ecology and physiology as humans to understand the human gut microbiome,” she said. “Old World monkeys like baboons appear to be the best starting point for this.”

According to Amato, a CIFAR Fellow in the Humans and the Microbiome Program, if ecology is really the most important driver of primate gut microbiomes, the human gut microbiome should be distinct from that of other apes. Furthermore, it should be more similar to other primates that use similar environments and diets as human ancestors did and have more similar associated physiological adaptations.

“Chimpanzees are often assumed to be the best models for humans in many aspects of science due to their high relatedness to us,” she said. “Our results show that this assumption is incorrect for the gut microbiome.”

Amato, also a faculty fellow with the University’s Institute for Policy Research, added that researchers need to think about the human gut microbiome and its evolution differently.

“This has implications for human evolution and microbial roles in it, as well as for microbial impacts on modern human health,” she said.

“We also need to start considering host ecology more carefully when we are choosing models for human microbiome research.”

Going forward Amato and her research team plan to explore in more detail which human gut microbial functions are shared with Old World monkeys and what impact they have on human biology and physiology.

“Pinpointing these relationships will provide further insight into the services gut microbes may have provided humans across evolution,” Amato said.

Source:

Northwestern University

Media Contacts:

Hilary Hurd Anyaso – Northwestern University

Image Source:

The image is in the public domain.

Original Research: Open access

“Convergence of human and Old World monkey gut microbiomes demonstrates the importance of human ecology over phylogeny”. Katherine R. Amato, Elizabeth K. Mallott, Daniel McDonald, Nathaniel J. Dominy, Tony Goldberg, Joanna E. Lambert, Larissa Swedell, Jessica L. Metcalf, Andres Gomez, Gillian A. O. Britton, Rebecca M. Stumpf, Steven R. Leigh and Rob Knight.

Genome Biology doi:10.1186/s13059-019-1807-z.

Abstract

Convergence of human and Old World monkey gut microbiomes demonstrates the importance of human ecology over phylogeny

Background

Comparative data from non-human primates provide insight into the processes that shaped the evolution of the human gut microbiome and highlight microbiome traits that differentiate humans from other primates. Here, in an effort to improve our understanding of the human microbiome, we compare gut microbiome composition and functional potential in 14 populations of humans from ten nations and 18 species of wild, non-human primates.

Results

Contrary to expectations from host phylogenetics, we find that human gut microbiome composition and functional potential are more similar to those of cercopithecines, a subfamily of Old World monkey, particularly baboons, than to those of African apes. Additionally, our data reveal more inter-individual variation in gut microbiome functional potential within the human species than across other primate species, suggesting that the human gut microbiome may exhibit more plasticity in response to environmental variation compared to that of other primates.

Conclusions

Given similarities of ancestral human habitats and dietary strategies to those of baboons, these findings suggest that convergent ecologies shaped the gut microbiomes of both humans and cercopithecines, perhaps through environmental exposure to microbes, diet, and/or associated physiological adaptations. Increased inter-individual variation in the human microbiome may be associated with human dietary diversity or the ability of humans to inhabit novel environments. Overall, these findings show that diet, ecology, and physiological adaptations are more important than host-microbe co-diversification in shaping the human microbiome, providing a key foundation for comparative analyses of the role of the microbiome in human biology and health.