Summary: A new study reports people use confirmation bias, even when a decision they make has little to no consequence.

Source: Cell Press.

People have a tendency to interpret new information in a way that supports their pre-existing beliefs, a phenomenon known as confirmation bias. Once they’ve made a decision about which house to buy, which school to send their kids to, or which political candidate to vote for, they have a tendency to interpret new evidence such that it reassures them they’ve made the right call. Now, researchers reporting in Current Biology on September 13 have shown that people will do the same thing even when the decision they’ve made pertains to a choice that is rather less consequential: which direction a series of dots is moving and whether the average of a series of numbers is greater or less than 50.

“Confirmation biases have previously only been established in the domains of higher cognition or subjective preferences,” for example in individuals’ preferences for one consumer product or another, says Tobias Donner from University Medical Center Hamburg-Eppendorf (UKE), Germany. “It was rather striking for us to see that people displayed clear signs of confirmation bias when judging on sensory input that we expected to be subjectively neutral to them.”

The findings by a team of researchers from UKE and Tel Aviv University, Israel, suggest that confirmation bias is linked to selective attention, a process in which people react to certain bits of information or stimuli and not others when several are presented at the same time. They also set the stage for studies to unravel the underlying brain mechanisms, the researchers say.

Although confirmation bias is well known, it hadn’t been clear what drives it. Is it that people, after making a decision, become less sensitive to new information? Or do they actually filter new information so as to reduce conflict with the decision they’ve already made?

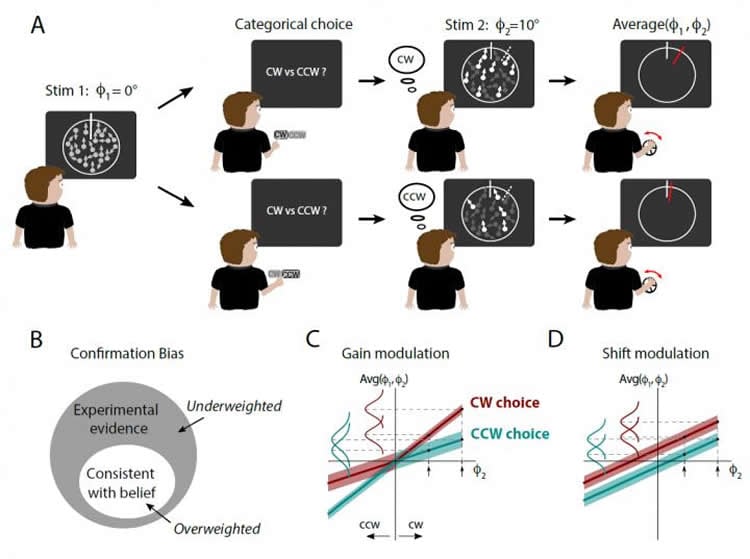

To explore this question, the researchers, including first authors Bharath Talluri and Anne Urai, both from UKE, asked study participants to look at two successive movies featuring a cloud of small white dots on a white computer screen. Their task was to report the direction the coherently moving dots, which was challenging because these dots were embedded in many more dots that moved about randomly. After the first movie, participants were asked to choose between two categorical options: whether the coherent motion pointed clockwise or counterclockwise from a reference line drawn next to the cloud of dots. After the second movie, they were asked to drag the mouse over the screen to indicate their best continuous estimate of the average direction across both movies they had seen.

The experiments showed that participants, after making an initial call based on the first movie, were more likely to use subsequent evidence that was consistent with their initial choice to make a final judgment the second time around. The finding suggests that the initial choice a person made in the simple visual motion task acts as a cue, selectively directing their attention toward incoming information that’s in agreement.

In a second series of experiments, the researchers presented a related numerical task. At first, they were asked to judge whether a series of eight two-digit numbers averaged greater or less than 50. In a second, they were asked to provide a continuous estimate of the average between 10 and 90. Again, participants’ answers showed a pattern of confirmation bias and selective attention.

The researchers say the findings help to identify the source of confirmation biases, with implications for understanding the bounds of human rationality. For those of us attempting to make informed decisions in the real world, the new study offers a reminder.

“Contrary to a common phrase, first impression does not have to be the last impression,” Talluri says. “Such impressions, or choices, lead us to evaluate information in their favor. By acknowledging the fact that we selectively prioritize information agreeing with our previous choices, we could attempt to actively suppress this bias, at least in cases of critical significance, like evaluating job candidates or making policies that impact a large section of the society.”

Funding: This research was supported by grants from the German Research Foundation, the German Academic Exchange Service, and a Marie Curie Individual Fellowship.

Source: Carly Britton – Cell Press

Publisher: Organized by NeuroscienceNews.com.

Image Source: NeuroscienceNews.com image is credited to Prat-Ortega & de la Rocha, Current Biology.

Original Research: Open access research for “Confirmation Bias through Selective Overweighting of Choice-Consistent Evidence” by Bharath Chandra Talluri, Anne E. Urai, Konstantinos Tsetsos, Marius Usher, and Tobias H. Donner in Current Biology. Published September 13 2018.

doi:10.1016/j.cub.2018.07.052

[cbtabs][cbtab title=”MLA”]Cell Press”People Show Confirmation Bias Even About Which Way Dots are Moving.” NeuroscienceNews. NeuroscienceNews, 13 September 2018.

<https://neurosciencenews.com/confirmation-bias-dots-9860/>.[/cbtab][cbtab title=”APA”]Cell Press(2018, September 13). People Show Confirmation Bias Even About Which Way Dots are Moving. NeuroscienceNews. Retrieved September 13, 2018 from https://neurosciencenews.com/confirmation-bias-dots-9860/[/cbtab][cbtab title=”Chicago”]Cell Press”People Show Confirmation Bias Even About Which Way Dots are Moving.” https://neurosciencenews.com/confirmation-bias-dots-9860/ (accessed September 13, 2018).[/cbtab][/cbtabs]

Abstract

Confirmation Bias through Selective Overweighting of Choice-Consistent Evidence

People’s assessments of the state of the world often deviate systematically from the information available to them. Such biases can originate from people’s own decisions: committing to a categorical proposition, or a course of action, biases subsequent judgment and decision-making. This phenomenon, called confirmation bias, has been explained as suppression of post-decisional dissonance. Here, we provide insights into the underlying mechanism. It is commonly held that decisions result from the accumulation of samples of evidence informing about the state of the world. We hypothesized that choices bias the accumulation process by selectively altering the weighting (gain) of subsequent evidence, akin to selective attention. We developed a novel psychophysical task to test this idea. Participants viewed two successive random dot motion stimuli and made two motion-direction judgments: a categorical discrimination after the first stimulus and a continuous estimation of the overall direction across both stimuli after the second stimulus. Participants’ sensitivity for the second stimulus was selectively enhanced when that stimulus was consistent with the initial choice (compared to both, first stimuli and choice-inconsistent second stimuli). A model entailing choice-dependent selective gain modulation explained this effect better than several alternative mechanisms. Choice-dependent gain modulation was also established in another task entailing averaging of numerical values instead of motion directions. We conclude that intermittent choices direct selective attention during the evaluation of subsequent evidence, possibly due to decision-related feedback in the brain. Our results point to a recurrent interplay between decision-making and selective attention.