University of Adelaide researchers have shown that intelligence in animal species can be estimated by the size of the holes in the skull through which the arteries pass.

Published online ahead of print in the Journal of Experimental Biology, the researchers in the School of Biological Sciences show that the connection between intelligence and hole size stems from brain activity being related to brain metabolic rate.

“A human brain contains nearly 100 billion nerve cells with connections measured in the trillions,” says project leader, Professor Emeritus Roger Seymour. “Each cell and connection uses a minute amount of energy but, added together, the whole brain uses about 20% of a person’s resting metabolic rate.

“It is not known how humans evolved to this state because direct measurements of brain metabolic rate have not been made in living monkeys and apes. However, we found that it is possible to estimate brain metabolic rate from the size of the arteries that supply the brain with blood.

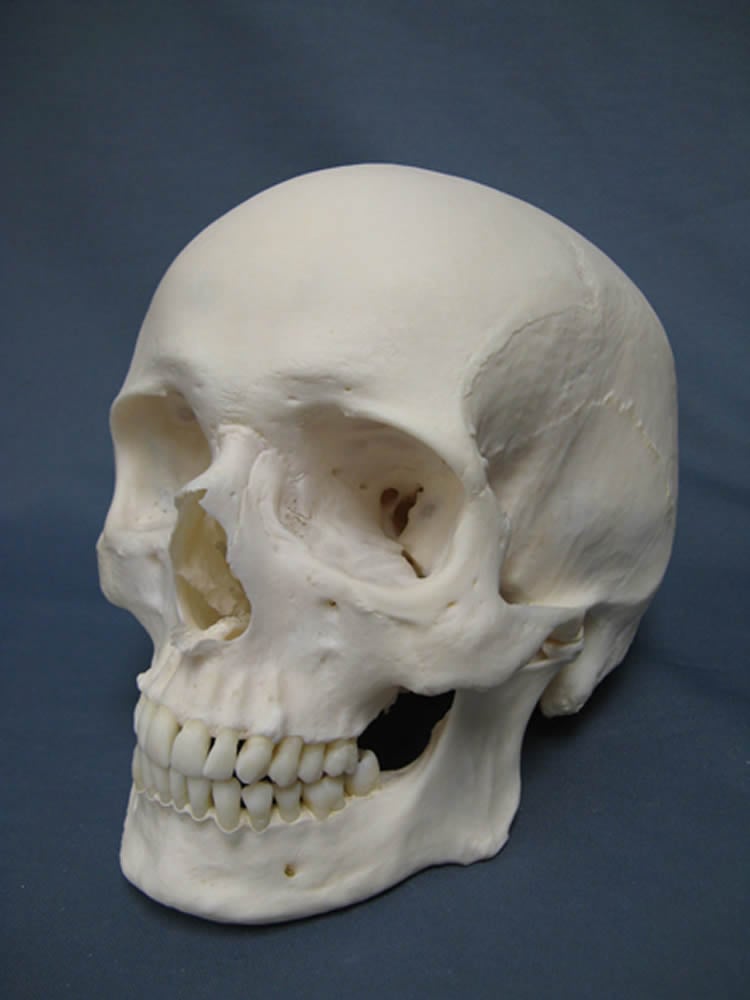

“Arteries continually adjust their diameter to match the amount of blood that an organ needs by sensing the velocity next to the vessel wall. If it is too fast, then the artery grows larger, too slow and the artery shrinks. If an artery passes through a bone, then simply measuring the size of the hole can indicate the blood flow rate and in turn the metabolic rate of the organ inside.”

Professor Seymour, and former Honours student Sophie Angove, measured the ‘carotid foramina’ (which allow passage of the internal carotid arteries servicing the brain) in primates and marsupials and found large differences.

“During the course of primate evolution, body size increased from small, tree-dwelling animals, through larger monkeys and finally the largest apes and humans,” says Professor Seymour.

“Our analysis showed that on one hand, brain size increased with body size similarly in the two groups. On the other hand, blood flow rate in relation to brain size was very different. The relative blood flow rate increased much faster in primates than in marsupials.

“The significant result was that blood flow rate and presumably brain metabolic rate increased with brain volume much faster than expected for mammals in general. By the time of the great apes, blood flow was about 280% higher than expected.

“The difference between primates and other mammals lies not in the size of the brain, but in its relative metabolic rate. High metabolic rate correlates with the evolution of greater cognitive ability and complex social behaviour among primates.”

Source: University of Adelaide

Image Credit: The image is credited to Sklmsta and is in the public domain

Original Research: Abstract for “Scaling of cerebral blood perfusion in primates and marsupials” by Roger S. Seymour, Sophie E. Angove, Edward P. Snelling and Phillip Cassey in Journal of Experimental Biology. Published online June 17 2015 doi:10.1242/jeb.124826

Abstract

Scaling of cerebral blood perfusion in primates and marsupials

The evolution of primates involved increasing body size, brain size and presumably cognitive ability. Cognition is related to neural activity, metabolic rate and blood flow rate to the cerebral cortex. These parameters are difficult to quantify in living animals. This study shows that it is possible to determine the rate of cortical brain perfusion from the size of the internal carotid artery foramina in skulls of certain mammals, including haplorrhine primates and diprotodont marsupials. We quantify combined blood flow rate in both internal carotid arteries as a proxy of brain metabolism in 34 species of haplorrhine primates (0.116–145 kg body mass) and compare it to the same analysis for 19 species of diprotodont marsupials (0.014–46 kg). Brain volume is related to body mass by essentially the same exponent of 0.71 in both groups. Flow rate increases with haplorrhine brain volume to the 0.95 power, which is significantly higher than the exponent (0.75) expected for most organs according to “Kleiber’s Law”. By comparison, the exponent is 0.73 in marsupials. Thus the brain perfusion rate increases with body size and brain size much faster in primates than in marsupials. The trajectory of cerebral perfusion in primates is set by the phylogenetically older groups (New and Old World monkeys, lesser apes), and the phylogenetically younger groups (great apes, including humans) fall near the line, with the highest perfusion. This may be associated with disproportionate increases in cortical surface area and mental capacity in the highly social, larger primates.

“Scaling of cerebral blood perfusion in primates and marsupials” by Roger S. Seymour, Sophie E. Angove, Edward P. Snelling and Phillip Cassey in Journal of Experimental Biology. Published online June 17 2015 doi:10.1242/jeb.124826