Summary: A new neuroimaging study reveals the brains of teenage girls who self harm show similar features to adults with borderline personality disorder.

Source: Ohio State University.

The brains of teenage girls who engage in serious forms of self-harm, including cutting, show features similar to those seen in adults with borderline personality disorder, a severe and hard-to-treat mental illness, a new study has found.

Reduced brain volumes seen in these girls confirms biological – and not just behavioral – changes and should prompt additional efforts to prevent and treat self-inflicted injury, a known risk factor for suicide, said study lead author Theodore Beauchaine, a professor of psychology at The Ohio State University.

This research is the first to highlight physical changes in the brain in teenage girls who harm themselves.

The findings are especially important given recent increases in self-harm in the U.S., which now affects as many as 20 percent of adolescents and is being seen earlier in childhood, Beauchaine said.

“Girls are initiating self-injury at younger and younger ages, many before age 10,” he said.

Cutting and other forms of self-harm often precede suicide, which increased among 10- to 14-year-old girls by 300 percent from 1999 to 2014, according to data from the Centers for Disease Control and Prevention. During that same time, there was a 53 percent increase in suicide in older teen girls and young women. Self-injury also has been linked to later diagnosis of depression and borderline personality disorder.

In adults with borderline personality disorder, structural and functional abnormalities are well-documented in several areas of the brain that help regulate emotions.

But until this research, nobody had looked at the brains of adolescents who engage in self-harm to see if there are similar changes.

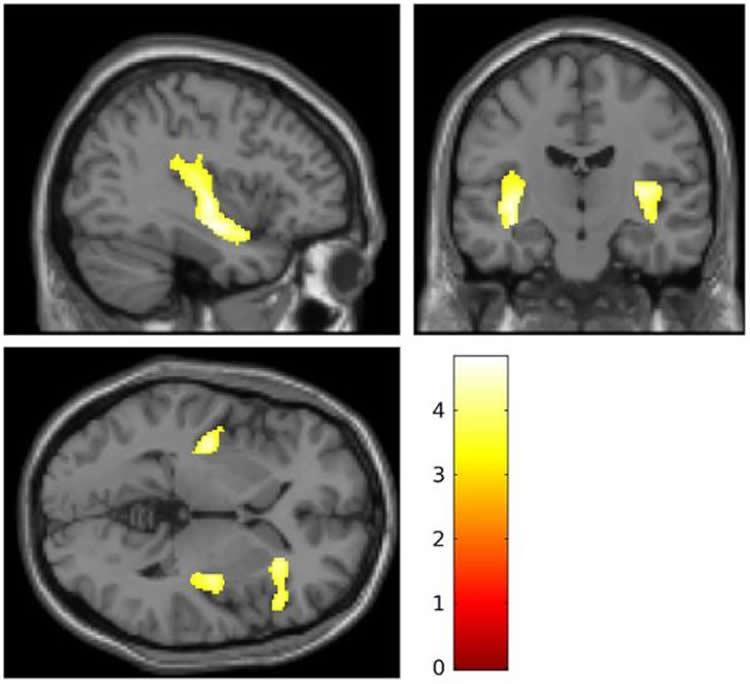

The new study, which appears in the journal Development and Psychopathology, included 20 teenage girls with a history of severe self-injury and 20 girls with no history of self-harm. Each girl underwent magnetic resonance imaging of her brain. When the researchers compared overall brain volumes of the 20 self-injuring girls with those in the control group, they found clear decreases in volume in parts of the brain called the insular cortex and inferior frontal gyrus.

These regions, which are next to one another, are two of several areas where brain volumes are smaller in adults with borderline personality disorder, or BPD, which, like cutting and other forms of self-harm, is more common among females. Brain volume losses are also well-documented in people who’ve undergone abuse, neglect and trauma, Beauchaine said.

The study also found a correlation between brain volume and the girls’ self-reported levels of emotion dysregulation, which were gathered during interviews prior to the brain scans.

Beauchaine said this study does not mean that all girls who harm themselves will go on to develop BPD – but it does highlight a clear need to do a better job with prevention and early intervention.

“These girls are at high risk for eventual suicide. Self-injury is the strongest predictor of suicide outside of previous suicide attempts,” Beauchaine said. “But there’s most likely an opportunity here to prevent that. We know that these brain regions are really sensitive to outside factors, both positive and negative, and that they continue to develop all the way into the mid-20s,” he said.

Adolescents who self-injure are more anxious, more depressed and more hostile than their peers who are also referred to mental health experts, previous studies have shown. This new brain-volume evidence bolsters the argument that self-injury should be viewed as a potential sign of serious, life-threatening illness, Beauchaine said, adding that there are no major prevention projects currently aimed at pre-adolescent girls in the United States. Instead, most current interventions start in adolescence when risk for self-harm is greatest.

“A lot of people react to girls who cut by saying, ‘She’s just doing it for attention, she should just knock it off,’ but we need to take this seriously and focus on prevention. It’s far easier to prevent a problem than to reverse it,” he said.

He said it’s important to recognize that the research does not establish whether the decreased brain volume seen in the study preceded the self-harm, or emerged after the girls began to injure themselves.

Further studies looking at brain changes are needed to help researchers better understand the relationship between structural differences and self-harm and how those might correspond to BPD and other mental disorders down the road, Beauchaine said.

“If we can learn more about how adults with psychiatric disorders got there, we are in a much better position to take care of people with these illnesses, or even stop them from happening in the first place,” he said.

A previously published study in these same girls applied functional MRI during a task in which they could receive monetary rewards. The researchers saw diminished brain responses to reward in those girls with a history of self-harm – results that looked similar to previous studies of adults with mood disorders and borderline personality disorder.

“Self-injury is a phenomenon that’s increasing, and that’s less common outside of the United States. It’s saying something about our culture that this is happening, and we should do whatever we can to look for ways to prevent it,” Beauchaine said.

Source: Theodore Beauchaine – Ohio State University

Publisher: Organized by NeuroscienceNews.com.

Image Source: NeuroscienceNews.com image is credited to Ohio State University.

Original Research: Abstract for “Self-injuring adolescent girls exhibit insular cortex volumetric abnormalities that are similar to those seen in adults with borderline personality disorder” by Theodore P. Beauchaine, Colin L. Sauder, Christina M. Derbidge, Lauren L. Uyeji in Development and Psychopathology. Published November 5 2018.

doi:10.1017/S0954579418000822

[cbtabs][cbtab title=”MLA”]Ohio State University”Brain Changes Found in Self-Injuring Teen Girls Similar to BPD.” NeuroscienceNews. NeuroscienceNews, 13 November 2018.

<https://neurosciencenews.com/self-harm-brain-girls-bpd-10190/>.[/cbtab][cbtab title=”APA”]Ohio State University(2018, November 13). Brain Changes Found in Self-Injuring Teen Girls Similar to BPD. NeuroscienceNews. Retrieved November 13, 2018 from https://neurosciencenews.com/self-harm-brain-girls-bpd-10190/[/cbtab][cbtab title=”Chicago”]Ohio State University”Brain Changes Found in Self-Injuring Teen Girls Similar to BPD.” https://neurosciencenews.com/self-harm-brain-girls-bpd-10190/ (accessed November 13, 2018).[/cbtab][/cbtabs]

Abstract

Self-injuring adolescent girls exhibit insular cortex volumetric abnormalities that are similar to those seen in adults with borderline personality disorder

Self-inflicted injury (SII) in adolescence is a serious public health concern that portends prospective vulnerability to internalizing and externalizing psychopathology, borderline personality development, suicide attempts, and suicide. To date, however, our understanding of neurobiological vulnerabilities to SII is limited. Behaviorally, affect dysregulation is common among those who self-injure. This suggests ineffective cortical modulation of emotion, as observed among adults with borderline personality disorder. In borderline samples, structural and functional abnormalities are observed in several frontal regions that subserve emotion regulation (e.g., anterior cingulate, insula, dorsolateral prefrontal cortex). However, no volumetric analyses of cortical brain regions have been conducted among self-injuring adolescents. We used voxel-based morphometry to compare cortical gray matter volumes between self-injuring adolescent girls, ages 13–19 years (n = 20), and controls (n = 20). Whole-brain analyses revealed reduced gray matter volumes among self-injurers in the insular cortex bilaterally, and in the right inferior frontal gyrus, an adjacent neural structure also implicated in emotion and self-regulation. Insular and inferior frontal gyrus gray matter volumes correlated inversely with self-reported emotion dysregulation, over-and-above effects of psychopathology. Findings are consistent with an emotion dysregulation construal of SII, and indicate structural abnormalities in some but not all cortical brain regions implicated in borderline personality disorder among adults.