Similarities found between HIV-associated brain damage and impairment from genetic fat-storage disease.

Johns Hopkins scientists have found that levels of certain fats found in cerebral spinal fluid can predict which patients with HIV are more likely to become intellectually impaired.

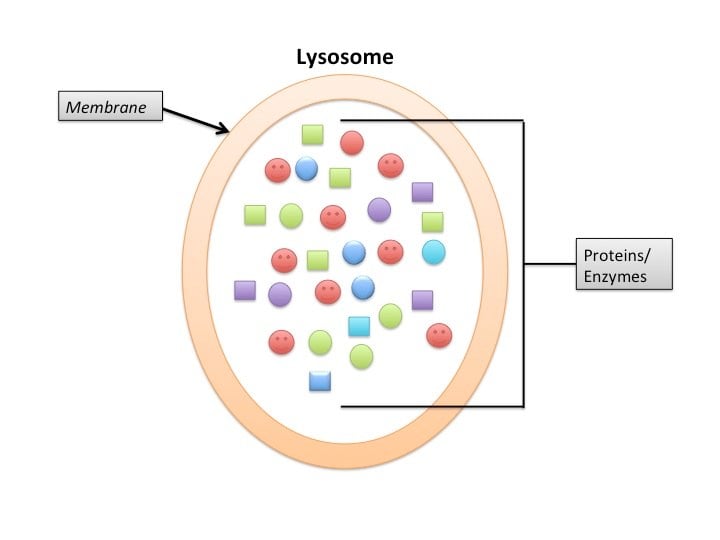

The researchers believe that these fat markers reflect disease-associated changes in how the brain metabolizes these fat molecules. These changes disrupt the brain cells’ ability to regulate the activity of cells’ “garbage disposals” meant to degrade and flush the brain of molecular debris. In this case, too much cholesterol and a fat known as sphingomyelin build up in the lysosomes — the garbage disposals — backing up waste and leading to often debilitating cognitive declines.

As many as half of patients infected with HIV will develop some form of cognitive impairment, ranging from mild (trouble counting change or driving a car) to frank dementia (an inability to manage activities of every day life), but no tests have been available to predict which people were more likely to suffer cognitive losses.

“Every researcher of neurodegenerative disease is chasing biomarkers for the same reason: It’s better to identify problems before they strike,” says Norman J. Haughey, Ph.D., an associate professor in the departments of neurology and psychiatry and behavioral sciences at the Johns Hopkins University School of Medicine. He led the current study described online in the journal Neurology.

“It’s very hard to reverse brain damage after it starts,” he says. “Instead, we want to figure out who is likely to lose cognitive function and stop the damage before it happens.”

Haughey and his team analyzed 321 cerebral spinal fluid samples collected from seven test sites across the continental United States, Hawaii and Puerto Rico. The samples came from 291 HIV-positive participants and 30 HIV-negative subjects. The investigators found that early accumulations of a small number of these fat molecules could predict the probability of cognitive decline. As cognitive function declined in these patients, the number of different types of fat molecules that accumulated increased. The types of accumulating fat molecules in HIV were very similar to those that accumulate in inherited forms of a class of diseases called lysosomal storage disorders. This suggests that in some HIV-infected patients, the brain is retaining more of these fats, and this may disrupt the function of lysosomes.

Haughey says he believes some of these impairments in the metabolism of these fats found in people with HIV stems from the infection itself, while others may be linked to the lifesaving antiretroviral therapy taken by most people with HIV. The medications have been associated with elevated blood cholesterol and triglycerides, along with a host of other side effects. Those with HIV are now taking these drugs for decades and the complications from long-term use have not been well studied, he says.

The similarities between the metabolic disturbances in HIV-infected individuals and those apparent in lysosomal storage disorders are enabling Haughey and his team to collaborate with researchers who study genetic lysosomal storage diseases, and who are developing experimental treatments to clear the fat buildup. They are currently exploring dietary and pharmacological interventions designed to restore balance that could potentially restore brain metabolism in HIV-infected individuals, and in doing so could promote good brain health by ensuring the lysosomes function properly.

Notes about this neurology and cognitive decline research

The study was supported by grants from the National Institutes of Health’s National Institute on Alcohol Abuse and Alcoholism (AA0017408), National Institute of Mental Health (MH077542, MH075673, MH071150, MH61427, MH220005), the National Institute on Aging (AG034849), National Institute of Neurological Disorders and Stroke (NS56883, U54NS43011, S11NS46278), National Institute on Minority Health and Health Disparities (8U54MD007587), the CNS HIV Anti-Retroviral Therapy Effects Research (CHARTER) Study (HHSN271201000027C and HHSN271201000030C) and the National Center for Research Resources (1U54RR026139-01A1).

Other Johns Hopkins researchers contributing to this study include Veera Venkata Ratnam Bandaru, Ph.D.; Michelle M. Mielke, Ph.D.; Ned Sacktor, M.D.; Justin C. McArthur, M.B.B.S.; Carlos Pardo, M.D.; and Peter Calabresi, M.D.

Contact: Stephanie Desmon – Johns Hopkins Medicine

Source: Johns Hopkins Medicine press release

Image Source: The structure of a lysosome image is credited to lumoreno and is licensed as Creative Commons Attribution-Share Alike 3.0 Unported

Original Research: Abstract for “A lipid storage–like disorder contributes to cognitive decline in HIV-infected subjects” by Veera Venkata Ratnam Bandaru, Michelle M. Mielke, Ned Sacktor, Justin C. McArthur, Igor Grant, Scott Letendre, Linda Chang, Valerie Wojna, Carlos Pardo, Peter Calabresi, Sody Munsaka, and Norman J. Haughey in Neurology. Published online September 11 2013 doi: 10.1212/WNL.0b013e3182a9565e