Summary: UCSF researchers report neural stem cells only have a very limited capacity to replenish brain tissue.

Source: UCSF.

It used to be that everyone knew that you are born with all the brain cells you’ll ever have. Then UC San Francisco’s Arturo Alvarez-Buylla, PhD, and other neuroscientists discovered in birds and mice that stem cells in certain parts of the brain do produce new neurons throughout the animal’s life.

Ever since, researchers have been eager to find how we might improve our own brain function by boosting its production of new neurons.

Many researchers have long assumed that most stem cells in the body can produce new cells indefinitely, but new research in mice by Alvarez-Buylla’s lab in UCSF’s Eli and Edythe Broad Center of Regeneration Medicine shows that this is not the case in the brain.

Kirsten Obernier, PhD, a postdoctoral researcher in Alvarez-Buylla’s lab, spent six years trying to understand how the brain avoids running out of neural stem cells by catching the cells in the act of dividing. “In the end it was a matter of German determination,” she joked.

By delicately labeling stem cells in the brains of live mice and recording the fates of their offspring, Obernier discovered that the cells don’t divide in a self-renewing fashion, as the field had predicted. Instead, most stem cell divisions produce offspring fated to develop into neurons, reducing the number of stem cells remaining.

The findings surprisingly demonstrate that neural stem cells only have a very limited capacity to replenish brain tissue. This may allow brain regeneration over a mouse’s brief lifespan, Alvarez-Buylla says, but it’s not clear how it could be maintained for the life of longer-lived creatures like ourselves.

“The adult brain seems to carefully choreograph how neural stem cells divide, how many times they divide and whether they do so to replenish them-self or to produce neurons,” Alvarez Buylla added. “Learning these properties about stem cells in the brain is essential for any future attempt to entice these cells to make new neurons for brain repair.”

To get a closer look how these cells divide, Obernier devised a technique for recording movies of their behavior in laboratory dishes without removing them from the surrounding neural tissue that forms their supportive niche.

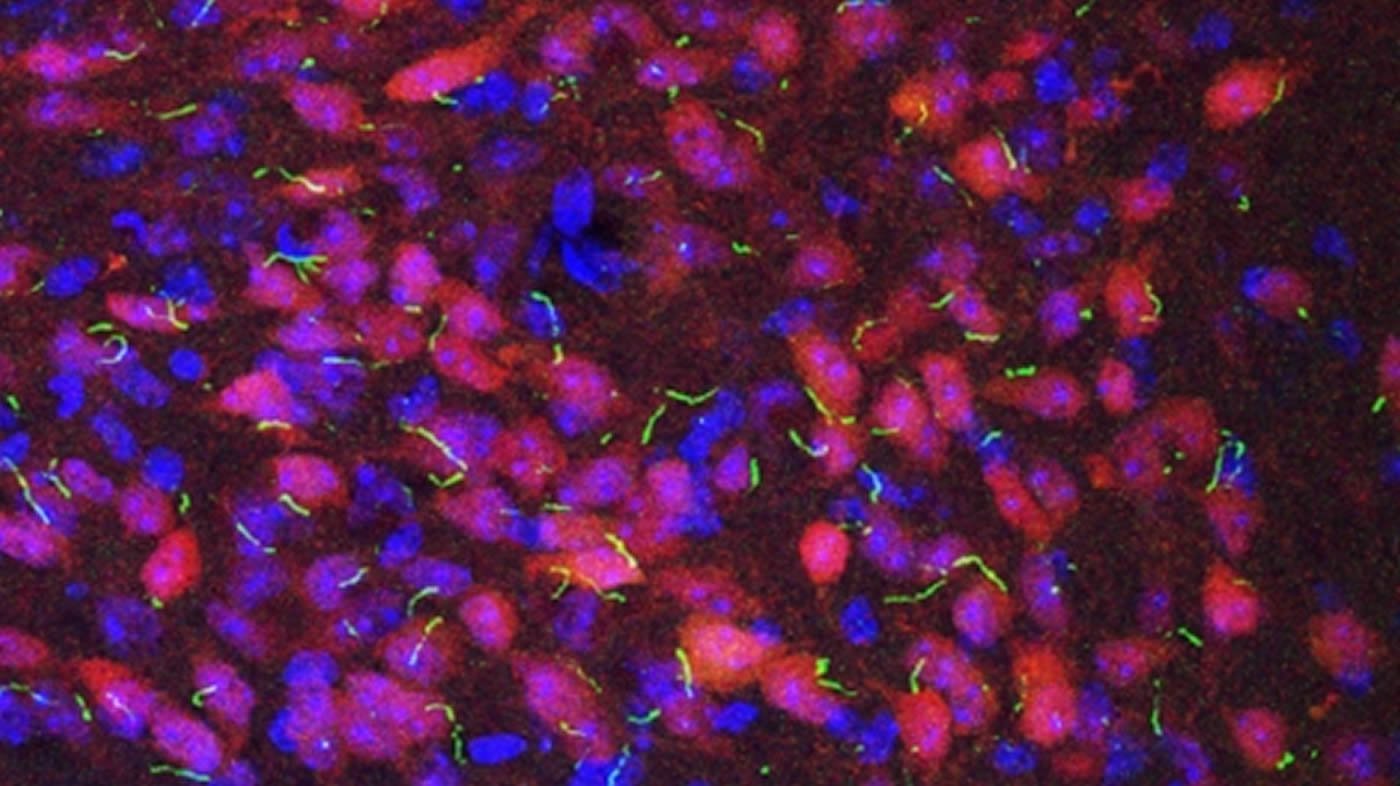

The videos confirmed the unorthodox new mode of division Obernier’s labeling experiments had implied, but also revealed the cells’ surprising dynamism: a long tail that touches and probes nearby blood vessels, short arms that poke and prod other stem cells, and a tongue-like antenna that pokes into the nearby ventricular space, as if to “taste” the cerebrospinal fluid there.

“We had seen these cells’ complex shapes before in still images, but the movies revealed that they’re constantly exploring their environment,” Obernier said. “These cells may be actively probing for signals about when more new neurons are needed.”

Source: Nicholas Weiler – UCSF

Publisher: Organized by NeuroscienceNews.com.

Image Source: NeuroscienceNews.com image is credited to Yi Wang, Vaisse Lab.

Original Research: Abstract in Cell Stem Cell.

doi:10.1016/j.stem.2018.01.003

[cbtabs][cbtab title=”MLA”]UCSF “Creation of New Brain Cells May Be Limited.” NeuroscienceNews. NeuroscienceNews, 7 February 2018.

<https://neurosciencenews.com/neurogenesis-limits-8444/>.[/cbtab][cbtab title=”APA”]UCSF (2018, February 7). Creation of New Brain Cells May Be Limited. NeuroscienceNews. Retrieved February 7, 2018 from https://neurosciencenews.com/neurogenesis-limits-8444/[/cbtab][cbtab title=”Chicago”]UCSF “Creation of New Brain Cells May Be Limited.” https://neurosciencenews.com/neurogenesis-limits-8444/ (accessed February 7, 2018).[/cbtab][/cbtabs]

Abstract

Adult Neurogenesis Is Sustained by Symmetric Self-Renewal and Differentiation

Highlights

•V-SVZ neurogenesis is sustained by symmetric divisions of neural stem cells (NSCs)

•NSCs symmetrically self-renew and generate neurons later in life

•Symmetric consuming NSC divisions generate transient-amplifying cells

•With time, some self-renewed NSCs lose apical contact with the ventricle

Summary

Somatic stem cells have been identified in multiple adult tissues. Whether self-renewal occurs symmetrically or asymmetrically is key to understanding long-term stem cell maintenance and generation of progeny for cell replacement. In the adult mouse brain, neural stem cells (NSCs) (B1 cells) are retained in the walls of the lateral ventricles (ventricular-subventricular zone [V-SVZ]). The mechanism of B1 cell retention into adulthood for lifelong neurogenesis is unknown. Using multiple clonal labeling techniques, we show that the vast majority of B1 cells divide symmetrically. Whereas 20%–30% symmetrically self-renew and can remain in the niche for several months before generating neurons, 70%–80% undergo consuming divisions generating progeny, resulting in the depletion of B1 cells over time. This cellular mechanism decouples self-renewal from the generation of progeny. Limited rounds of symmetric self-renewal and consuming symmetric differentiation divisions can explain the levels of neurogenesis observed throughout life.